Posts Tagged ‘ThyssenKrupp AG’

Sunday, August 19th, 2018

|

The official Second World War history put out by the Thyssen complex has always been that Fritz Thyssen supported the Nazis for a while but, being against war, fled Germany only to be recaptured and locked up in a concentration camp. Of his brother Heinrich it was said he was a Hungarian living in Switzerland with no connection to either Germany or the Nazis. When we revealed in our book ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’ (2007) that this was far from the truth, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation launched an academic response, which this book forms part of. It is mostly concerned with the press coverage of the Thyssens and, at 546 pages, is the longest in the series, which is why this review runs to 20 pages. The book continues the general theme that, while the various authors are revealing information contradicting the old Thyssen myths, overall these myths are nonetheless kept very much alive.

As we will see, Felix de Taillez would qualify this as being ‘entirely understandable’, since the Thyssens and the Thyssen company had ‘a reputation to defend’. (In 1997 Thyssen AG merged with Krupp AG to become thyssenkrupp, which is currently in major economic turmoil). De Taillez’s favourite tool in avoiding the making of justified criticism is to say that something is „remarkable“. He uses the term exceedingly frequently throughout the book, which comes across as highly staged. It is a vague term not expected with such high frequency in an academic work. De Taillez seems to use it to create an atmosphere of ‘spin’ which can beguile people with no previous knowledge of the subject matter. It harbours the danger of turning his otherwise excellent work of history into one of public relations.

To the general public, De Taillez pulls off these two faces particularly well and it comes as no surprise that he has landed a prestigious job as an advisor – presumably on German history – at the University of the German Armed Forces in Munich, which oversees the training of the officers corps. But there are inconsistencies in his book presentation and the fact his theories now seem to feed into the country’s state-sponsored history make these particularly concerning. His official online presence at the Ludwig Maximillian University promises:

‘(This project) will interpret the brothers Fritz and Heinrich Thyssens as a UNIT OF ALMOST COMPLEMENTARY OPPOSITE NUMBERS, BECAUSE THE APPARENTLY APOLITICAL HEINRICH ACTED, EVEN THOUGH IN A CONCEALED MANNER, AT LEAST AS LASTINGLY, IN POLITICAL TERMS, AS FRITZ. Visibility, respectively invisibility’ appears, (from this perspective), as A ‘COORDINATED STRATEGY OF POLITICAL ACTION’.

This statement appears to promise a new honesty and yet leaves one puzzled, as it does not appear in the book itself and is not, in fact, representative of the elaborations in the book. There, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s absence in the media is still principally explained by his involvement in a court case in London as a young man, in which he is said to have made such bad experiences with the press, that he subsequently – with his marriage in 1906 – retreated completely from public (especially German!) life, to be an apolitical, Hungarian nobleman.

This is also the version which family members have propagated ever since. Again recently Francesca Habsburg née Thyssen-Bornemisza, let herself be fêted in the pages of the Financial Times Weekend Magazine as pretender to the Austrian throne and ‘grand-daughter of a Hungarian Baron’. Which is certainly more pleasant than having to expose Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza correctly as a German commoner, weapons manufacturer and Nazi banker; especially when one suns oneself, as Habsburg-Thyssen does, in the beautiful appearance of the expensive art the family bought, at least in part, with the profits of these reprehensible activities.

Even the title chosen by Felix de Taillez is noticeably misleading, as it suggests that both brothers were anchored equally and intentionally, and as bourgeois members of society, within the public sphere. Yet these Thyssen brothers in particular, really did not see themselves as part of the middle class at all. Also less than one quarter of the book deals with Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza and then only with his explicitly authorised visibility in the exclusive, only partially public spheres of art collecting (which was already monitored comprehensibly by Johannes Gramlich) and horse racing (which we will deal with in a separate article following this review).

We expected de Taillez to show how, apart from his presence in these two domains, Heinrich Thyssen managed to stay consistently out of the media, and what he aimed to withhold from general view. After all, the newly created archive of the Thyssen Industrial History Foundation in Duisburg has an astonishing 840 continuous meters of hitherto unaccessed material (except by us) on the Thyssen-Bornemisza complex. But instead of letting the wind of Aufarbeitung blow through the holdings of the ThyssenKrupp AG archives and these newly acquired files, the public is once again fobbed off with crumbs.

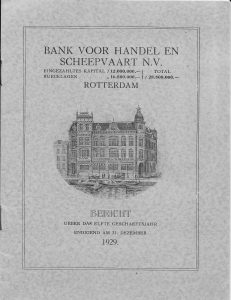

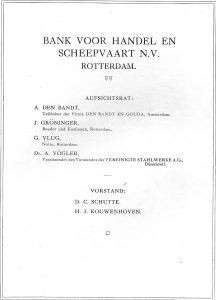

In this volume, as so far in the series, the politico-economical actions especially of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, remain mostly camouflaged, this time, as befits the subject matter, behind the statement that the brothers were ‘victims of biased reporting’ and ‘helplessly exposed to media mechanisms’. Felix de Taillez does not mention Heinrich’s involvement in private banking, which is by its very nature, highly secretive. He leaves his close friendship with Hermann Göring (a client of the August Thyssen Bank) untackled and keeps silent about the use of the bank by the ‘Abwehr’, the German counter-intelligence service. In so doing, he avoids giving any information about the mechanisms used in turn by the Thyssens, and particularly Heinrich, in order to manipulate the media and keep their activities out of its spotlight.

* * *

One of the insightful descriptions in this book is the statement that during the Ruhrkampf battle in 1923, Heinrich ‘cast his political lot in with Fritz’, that ‘in certain respects (…) he was even more radical than his brother (Fritz), as he rejected negotiations with the occupation force outright’. ‘Behind the scenes’, says de Taillez, Heinrich, ‘together with his associates, who had all linked together in a “patriotic movement of the Ruhr“, met leading members of the army and politicians in Berlin (…)’. – For unknown reasons, de Taillez does not mention who these “associates“ were -. As ‘finance administrator’ of the ‘Ruhr Protection Association’, Taillez continues, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza ‘helped organise propaganda in favour of Germany in all occupied territories’, (as well as in) ‘Holland, Switzerland, Alsace-Lorraine and Italy’.

One would like to ask Frau Habsburg why a man, who was allegedly a Hungarian Baron, would do such a thing. And why has it taken a century for these attitudes and actions of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza to see the light of day? Because over the years, a conscious strategy was at play, whereby the Thyssen complex portrayed the Thyssen brothers as if Fritz had been the German national hero and Heinrich free of all ‘German evil’. It is the ideal way in which to confuse the public concerning questions of power and guilt.

But as advantageous as such kinds of ‘legends of convenience’ might be, it is very time-consuming to uphold them. Because, if you believe Felix de Taillez, the world is full of ‘merciless’ left-wing writers who, for some unfathomable reason, insist on questioning things. This, according to him, is also the reason why, of all papers, ‘the social democrat paper “Vorwärts“’ in 1932 was leaked by a Dutch insider (and printed the information) that the Thyssen company ‘Vulcaan (was) favoured for the ore freight traffic of (the United Steelworks), by being the only shipping company enjoying very long-term contracts with the Düsseldorf steel giant. Furthermore the (United Steelworks) paid rates for this service, which were far above going market prices’.

One would assume that the fact part of the Thyssen fortune, which has been described so pointedly by Christopher Neumaier as ‘exorbitant’, seems to have been based on some dishonest business practices, should be condemned. But de Taillez allows himself instead the following comment: ‘Thus business connections were uncovered which the Thyssens had tried to camouflage under considerable efforts.’ As if acts of economic crime were an achievement and the real scandal their disclosure by those seeking the truth.

And de Taillez adds yet another layer to this twisted approach. Fritz Thyssen declared the lack of capital to be the Weimar Republic’s biggest economic problem. But when asked about his own capital flight from Germany, for instance in a 1924 interview with Ferdinand de Brinon, he circumvented the question. Absolutely understandable, in the eyes of de Taillez, as he had to maintain his reputation as a ‘dutyful German entrepreneur’. Whereby the artificiality of the Thyssens’ reputation, in the twinkling of an eye, receives an academic and, because of the author’s current position, a quasi stately seal of approval.

* * *

The lives of the Thyssen brothers Heinrich and Fritz teem with artificiality. There is their militarism, which de Taillez explains as their internalised connection to ‘army, tradition, faith and military practices’. Both trained in Hohenzollern elite regiments, however Heinrich declined war service and Fritz escaped it early by ‘having himself charged, on his own suggestion, with an official order by the Foreign Office to clarify the raw material situation for the Reich in the orient (Ottoman Empire)’. Stephan Wegener’s assertion that the Thyssens suffered high material losses through World War One is nothing but family folklore designed to shield unpalatable truths. Wegener, a member of the Josef Thyssen side of the family, conveniently leaves out that they were not only compensated by the German state, but made huge, fully audited profits supplying steel, armaments and submarines, with the assistance of forced labour. It is unforgivable that an academic such as Felix de Taillez and others in the series repeat the family legends of overall material war loss, as if they were fact.

The issue of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s adopted nationality shows most clearly what kinds of self-staging the family used. As he had to position himself as a ‘Hungarian’ to contrast Fritz, Heinrich insisted unforgivingly on his castle in Burgenland being called by its Hungarian name ‘Rohoncz’. He said he found the German version too ‘socialist’ (implying falsely that the German term had only come about in 1919 with the proclamation of the republic, see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, page 123). According to de Taillez, Heinrich even got into fights with the Burgenland County Government, the Austrian Federal Monuments Office, the Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture and the Foreign Office in Berlin. Ironically the castle administration sat somewhere completely different, namely with Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor in Rotterdam. ‘The Baron’ camouflaged himself twice and threefold; sedentary officials had no tools to counteract such extravagant strategies.

Fritz too opposed the abolishment of the German and Austrian monarchies and the rise of social democracy. According to de Taillez he saw Germany as a hard-pressed center surrounded by a tight circle formed by England, France, Italy and Russia and was of the opinion that ‘the big pressure from outside did not allow for the German national unification to proceed by democratic means’. Fritz thought social democrats as ‘moderate revolutionaries’ were ‘just as dangerous’ as more radical subversives. According to de Taillez, Thyssen wanted the ‘spirit of the worker’ to be ‘German’ and no more. While the unions were requesting increased rationalisations, shortening of working hours and increased wages, he wanted a ’Volk’ (people) strengthened by the increase of the working day from 8 to 10 (!) hours and an end to participative management (a German speciality, whereby workers representatives sit on the management board). But how could this be made palatable for the men returning from the horrors of the First World War, who were turning in droves to pacifist and democratic organisations?

According to Niels Löffelbein, George Mosse explains the rise of fascism with a ‘brutalisation’ of post-war political culture through the mass of soldiers, which led to a ‘dissolution of boundaries and a radicalisation of political might’. Angel Alcalde counters that the world war participants were increasingly ‘instrumentalised’ as anti-bolshevik fighters by the extreme right and the veterans organisations. This, says Alcalde, happened during the ‘mytho-motoric incubation period’ of the 1920s. Thus the connection between radical nationalism and war was celebrated within the cult for the fallen heroes (and those still willing to fight on). According to de Taillez, as early as October 1917, Fritz Thyssen submitted an enrollment declaration to the right-wing, nationalist Deutsche Vaterlandspartei (DVLP, German Patriotic Party). In 1927 he gave a speech during an event of the ‘Stahlhelm Bund der Frontsoldaten’ (Steel Helmet Association of Front-Line Soldiers), the ‘fighting force ready for violence’ of the Deutschnationale Volkspartei (DNVP) in his hometown of Mülheim. He is also said to have been ‘very close’ to the ‘Association of the anti-democratic, extreme right-wing Harzburger Front’.

Felix de Taillez writes that Thyssen supported the Austro-fascist home guard militias: ‘Via Anton Apold, the general manager of the Austrian-Alpine Mining Company (Österreichisch-Alpine Montangesellschaft) (…), which in its majority belonged to the United Steelworks, (…) there was a connection of Thyssen with the radical right-wing home guards of Austria’. ‘The Düsseldorf Peoples Paper (Düsseldorfer Volkszeitung) insinuated that the big German industrialist wished to test out, “on the limited battle field of Austria“, how the unions’ influence could be broken’.

Without the shadow of a doubt, these associations would have been backed by Heinrich as well, but as a purported Hungarian privatier, he managed to keep out of all media reports about the topic and thus was not publicly perceived as a supporter of the extreme right in the German-speaking world. By not clarifying this circumstance, de Taillez adds to the picture of Heinrich drawn by the series as not being in any way a sympathiser of the far right. It is an allegation based purely on the absence of public sources, which was deliberately engineered by Heinrich and his associates. Absence of proof is not proof of absence and this should have been exposed by de Taillez. It is not, as exposing Heinrich’s far right-wing sympathies would destroy the Thyssen family mythological reputation.

* * *

For the Thyssens, there were always conflicts of interests between their national affiliation and their economic ambitions. After they had transposed the ownership structures of their works to the neutral Netherlands before the First World War, Fritz and his father August participated shortly after the war in talks about the formation of a Rhenanian Republic. According to de Taillez, the accusation by the Workers and Soldiers Council was that they ‘had requested the separation of Rhenania-Westphalia and the occupation of the Ruhr by the Allies’. A waiter had reported the meeting and the Thyssens were soon accused of being ‘greedy hypocrites’ and ‘money bag patriots’; others said this was a slur on the loyally German industrialists. The case against them was dismissed (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 56) and Felix de Taillez writes that the waiter admitted to having lied. It does not cross his mind that this man might have needed to do so in order to keep his, or indeed any, job. Afterwards, Fritz Thyssen, who, according to de Taillez, ‘had a much higher status for German politics than a normal citizen’, was commissioned by the Foreign Office in Berlin to participate in the confidential follow-up negotiations for individual articles of the Versailles Peace Treaty.

Soon after the war, Fritz Thyssen also began to establish for himself an alternative domicile in Argentina by buying, first of all, the Estancia Don Roberto Lavaisse in the province of San Luis. The family’s connections with South America went back to pre-war times, when August Thyssen had founded in Buenos Aires a branch of the German-Overseas Trading Company of the Thyssen Works (Hamborn) (Deutsch-Überseeische Handelsgesellschaft der Thyssen’schen Werke). Since 1921 the company was called Compania Industrial & Mercantil Thyssen Limitada. In 1927 it took over the Lametal company and from them on ‘went under the name of Thyssen-Lametal S.A.’. According to de Taillez, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza sold it in 1927 for 4.8 million guilders to the United Steelworks. In Brazil too the family had owned property for years and advertised commercial trade there.

During the Ruhrkampf (battle against the Ruhr occupation) of 1923, which Fritz Thyssen allegedly saw as a ‘legitimate defence measure against foreign begrudgers’, he let himself be represented in the allied court by Friedrich Grimm, an avowed anti-semite and subsequent Nazi lawyer who, according to de Taillez, defended Nazi perpetrators after 1945 and downplayed Nazi crimes. In the eyes of the author, Thyssen was merely ‘talked up’ artificially as a ‘projectory surface’ for a ‘new German national identity’, respectively for a ‘free Germanness’, particularly by the New York Times and the Times of London. But the Ruhrkampf was the first occasion for Fritz to move out very publicly from the shadow of his almighty father, whose health had started to deteriorate, In our opinion, this motive of self-liberation is a factor in Fritz Thyssen’s publicly celebrated swing to the right that should not be underestimated.

If you listen to de Taillez, it must ‘remain open’, ‘whether Fritz Thyssen was captured by the world of a sometimes extreme nationalism, which had formed in Germany during the First World War’. What a pity that his wife Amelie Thyssen gets so little attention in this series, apart from her role as co-founder of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. According to a statement made by Heini Thyssen to us, there was certainly nothing ‘talked up’ about Amelie Thyssen’s politics and she indeed seems to have been national socialist in her strong German nationalism during this ‘1920s incubation period’ and beyond. Although time and again de Taillez describes how much Fritz depended on his wife’s opinions, he leaves the possibility of political influencing within this couple’s relationship completely unmentioned. Since Amelie was the driving force in successfully reclaiming the Thyssen organisation after the Second World War, any bad light on her would, once again, harm the Thyssen family mythological reputation.

Grimm’s argument before the court was characterised by his statement that ‘private assets such as Ruhr coal (…) legally could not simply be confiscated, in order to settle state debts, without compensating the owners’. Taillez alleges that the Ruhrkampf set in motion in Fritz Thyssen a ‘sense of political mission’, which ‘surpassed by far the activities in the interests of the business’. He concedes that Thyssen, by saying that the German economy could only recover ‘through even greater working output’, had incurred guilt: ‘through such public statements (…) he also contributed to the failing of the social partnership in the 1920s, which gravely endangered the democratic form of government in Germany’.

Eventually, Fritz would be indulged by Adolf Hitler with a promise to establish a Research and Development Department for Fritz’s concept of a corporate state. This unrequited activity encouraged Fritz in considerable political activity. Fritz was disappointed by his project’s lack of action, but, when he pointed this out to Hitler, was told: ‘I never made you any promises. I’ve nothing to thank you for. What you did for my movement you did for your own benefit and wrote it off as an insurance premium’ (quoted by Henry Ashby Turner Jr., see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 108).

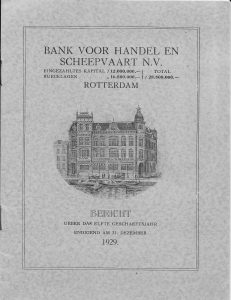

According to de Taillez, Fritz Thyssen followed his own business interests above all else, apart from situations when it was not completely clear to him ‘which path would served (these) most’. Within European rapprochement politics, he describes him as ‘ambiguous’. Thyssen critised the Weimar Republic in the French press as well as the North-American public sphere, described the German government as ‘weak and not trustworthy’ and thus ‘stuck the knife into German foreign politics in a difficult situation’. On the other hand, he criticised the ‘short-sighted and mean-spirited, selfish economic politics of the North Americans’. Thyssen ‘wanted bilateral exchange contracts for the traffic of raw materials, which were to put a stop to international financial speculations and achieve independence from exchange rates’. But when Fritz ‘(ranted) against finance techniques which (he said) were getting in the way of the real economy’, he failed to mention that the Thyssen family controlled 100% of three international banks and thereby was itself a global financial player (which, strangely, Felix de Taillez does not mention).

* * *

Although his group leader, Simone Derix, refuted this comprehensively, de Taillez continues to allege that Heinrich managed his inherited share of the family concern independently from Fritz’s. He says the relationship between the two brothers was bad. Now they might not have loved each other wholeheartedly; it is normal for there to be certain jealousies between siblings. Heini Thyssen told us how his father walked down Bahnhofstrasse in Zürich one day and changed to the other side of the street when he saw his brother Fritz. But this had indeed more to do with image than realities. Heini too wished to give the impression of discord, because his own, the Thyssen-Bornemisza side of the family, had managed to keep disassociated from discussions about the Third Reich. A photograph of the three brothers in 1938 (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 128) and here shows that there were no problems in their relationship. Instead of being objective, de Taillez repeats parrot-like old Thyssen-internal myths, which have become dogma. This is particularly ‘remarkable’ as he tells us, on the other hand, that he wants to ‘interpret’ both men as ‘a unit of almost complementary opposite numbers’, whose ‘visibility respectively invisibility’ appears (from this perspective) as a ‘coordinated strategy of political action’.

After Heinrich received his ‘exorbitant’ inheritance in 1926, for a few short years he invested massively into paintings and works of art, thereby following the example of his friend Eduard von der Heydt, who had moved to Switzerland that same year. Despite it never being housed there, he called his collection ‘Rohoncz Castle Collection’, to give the impression of it having grown organically over a long period of time, and being of an aristocratic cachet. As such he had it exhibited in 1930 in the Neue Pinakothek in Munich. But Friedrich Winkler of the State Museums in Berlin compared ‘Thyssen-Bornemisza’s methods (…) to Napoleon’s art theft’ and described him as ‘clueless, uninformed, limited and dependent on the opinions of dealers and experts’. Rudolf Buttmann, delegate of the Nazi party in the Bavarian County Parliament, called the collection ‘an entity gathered by dealers’. Many false attributions and fakes were decried and the whole thing descended into a veritable ‘media scandal’. According to de Taillez, the Munich Pinakothek was willing only in the case of 60 out of 428 paintings to take them temporarily into their own stock after the end of the exhibition.

But these were highly speculative times with an ‘increasing commercialisation of the art market’. Despite all the hoo-ha, Heinrich’s ‘calculation to have the value of his collection determined publicly’ came good (at 50 million RM – without de Taillez explaining how he would know of such a ‘calculation’). His enterprise was described as a ‘national deed’ in which ‘the whole of Germany was said to be interested’. He was described as a ‘saviour of German cultural goods’, who was endowed with a ‘bourgeois educational mandate’ over the public. Meanwhile, it was striking that Heinrich was not presented anywhere as the son of the famous Ruhr industrialist and creator of the family fortune, August Thyssen. Instead, he was made out to be ‘the great stranger’, a person of ominous flair who nobody seemed to know exactly where he came from. There needed to be just enough ‘Germanness’ tagged onto him to keep conservative Munich audiences happy, while still maintaining the illusion of Heinrich’s adopted Hungarianness. What is troubling is that de Taillez does not openly decry this as the obvious Thyssen manipulation of public perception that it was.

The town of Düsseldorf and its art museum, which were ‘leading amongst big German cities’ during the Weimar years in view of a ‘highly developed apparatus of communal public relations’, was used by Heinrich Thyssen over many years, according to de Taillez. He took himself for ‘such an important personality (…), that he could make demands on the local political sphere’. It appears nonsensical that de Taillez equally alleges that the national positioning of Heinrich in Germany was only down to the materials handed out to the press by his art advisor Rudolf Heinemann and the Düsseldorf mayor Robert Lehr and that it was not in Heinrich’s own sense. Heinrich had organised propaganda in favour of Germany, he also kept his German passport (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 55 – confirmed by Simone Derix) and accepted German compensation payments for war damages to his enterprises (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p.201 – confirmed by Harald Wixforth). It is incomprehensible why de Taillez makes such contradictory statements; unless the accusations levelled at the series’ output of having been influenced by the source of their sponsorship – the Fritz Thyssen Foundation – might be justified.

Felix de Taillez goes way further than he should by not just obfuscating existing Thyssen manipulations but even generating new ones. He writes: ‘Heinrich (reacted) to the debacle of the exhibition, namely by restructuring big parts of his collection afterwards, selling THE controversial paintings and only thereby creating the actual breakthrough to the collection which is today world renowned’. His underpinning reference is to Johannes Gramlich’s volume ‘The Thyssens As Art Collectors’, pages 263-273. There, however, only 32 paintings are mentioned as having been sold between 1930 and 1937. Thyssen-internal lists available to us show that 405 paintings bought by Heinrich up to 1930 were inherited by his children in 1948. This would mean that only 23 paintings had theoretically been sold between 1930 and 1948.

So there can be no talk of Heinrich ‘restructuring big parts of his collection (after the exhibition debacle)…….selling THE controversial paintings’, which makes it sound like ALL the controversial pictures exhibited by Thyssen in 1930 were subsequently sold by him.

Even today, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid contains at least 120 paintings from the 1930 Munich Exhibition. If there was any ‘restructuring’ of the 1930 collection, it was not done actively by Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, but happened passively following his death, mainly through inheritance share-outs (1948, as well as 1993 after Hans Heinrich (‘Heini’) Thyssen sold only half the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection to Spain – the other half went to his wife and four children).

There was also a sale specifically of German paintings in the 1950s by Heini Thyssen who, after the Nazi period, wanted to be seen as being even more disconnected from Germany (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 269). And of course, Heini Thyssen became an art collector on a completely different scale to his father and did indeed buy some very good, mostly modern, paintings.

Many of the questionable paintings exhibited in 1930, however, remained in Thyssen ownership and de Taillez’s assertion that they did not is misleading.

It must be remembered in this context that Heini Thyssen bought back most of the paintings that went to his siblings in the 1948 inheritance share out, so that most of the questionable 1930 paintings would have ended up in his possession. The Thyssens’ attitude has always been that once a painting had entered their inventory it was to be seen as beyond reproach. In this, they sought to emulate the prestige which the Rothschilds possessed. Most members of the general public, influenced by the media – who are possibly submitted to a VIP equivalent of the royal rota (whereby journalists are excluded from access to members of the royal family if they publish negative stories) -, have always seemed to accept this version of reality.

* * *

What is noticeable throughout the book and the series as a whole is that it comprises not a single personal quote from a living member of the Thyssen family. So much new history is being written about them and one wonders what they feel now that some of the plates that had, for so long and at great expense, been kept spinning in the air are starting to come tumbling down.

But Felix de Taillez would not be Felix de Taillez if he did not release us from the world of Thyssen art with yet another piece of white wash. Various art advisors, museum directors and the Baron himself had made contradictory statements about when exactly the paintings had been bought. Had they ever been at Rechnitz Castle, as the name of the collection suggested? Sometimes they said yes, sometimes no. The Thyssen-internal lists available to us show that he bought his first painting in 1928 and all works remained in safe deposits until the 1930 exhibition (the foreword to the exhibition catalogue makes this very clear – see here). Which did not, however, stop the Baron from saying sometimes that he had made his first art purchase in 1906, the year he married into Hungary.

In the 1930s, his lawyer did something similar with the Swiss authorities: ‘In connection with Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s move to Switzerland it is furthermore remarkable that the first exhibition of his collection in Munich was of financial use to him. For the import of his paintings and other works of art into Switzerland he was able to use, vis-a-vis the Swiss authorities, the reference to the exhibition with said catalogue as proof that around 250 valuable paintings had been in his possession already for a longer period of time. Through this gambit he was able to have the works of art moved to Lugano “for his personal enjoyment“ and exempt from customs duties’.

(The name of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s Ticino lawyer was Roberto van Aken, and it was not the only time he bent the truth on behalf of his client),

To recapitulate: Felix de Taillez applauds the outwitting of the Swiss customs authorities by Heinrich Thyssen’s malleable lawyer, seems to give as a reason why allegedly 250, not 428 paintings were moved to Switzerland, that the Baron had sold the questionable paintings and, at the same time, like Johannes Gramlich, leaves us completely in the dark as to when and how exactly this transfer of goods out of Germany is supposed to have taken place. As the collection at the time of the 1948 inheritance share-out contained a total of 542 paintings, he also leaves unexplained where the other almost 300 paintings are supposed to have come from and when they got into Switzerland.

The fact the Thyssens themselves were intransparent concerning this matter is understandable. But it is unacceptable that academics, having been commissioned almost a century later to work through the events in a claimed ‘independent’ manner, are behaving in the same way. Particularly as no family members have been quoted.

* * *

On the whole, while Felix de Taillez is remarkably obstinate in prolonging the myths surrounding Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, he seems somewhat more direct in his presentation of Fritz. We dont suggest the Fritz Thyssen Foundation or the Thyssen Industrial History Foundation have steered the results of these academic investigations. But the fact access to source materials and financial sponsorship were granted by these entities (on whose boards sits only ONE Thyssen family member, namely Georg Thyssen-Bornemisza, a descendant of Heinrich, not Fritz) must have led the authors to tread with a degree of ‘caution’ in their ultimate assessments.

Continuing on the theme of Fritz, following the putsch by General Jose Felix Uriburu, an ‘undemocratic decade’ began in Argentina in 1930, during which a ‘strong economic integration with Germany’ came about. According to de Taillez, ‘strongly extreme right-wing movements’ existed there from the 1890s onwards, and ‘already before the seizure of power in Germany’ the foreign organisation of the Nazi party ‘took hold (in Argentina) particularly well’ (see also ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 195). Lateron the La Plata newspaper reported that Fritz Thyssen in 1930 (!) proclaimed the ‘dawn of the coming, new Germany’ under Hitler in the Argentinian public. In 1934 he demanded in the Argentinian Journal (Argentinisches Tageblatt) the ‘unlimited power of the new (German) government in order to boost the economy’, which de Taillez describes as ‘remarkable’, after all he had ‘normally always insisted on big freedoms for the private economy’. De Taillez continues: ‘According to Thyssen, the concentration of power in the Nazi state offered the important advantage, of making decisions, without having to take “half-measures“ and “make compromises“ like in the “party state contaminated by Marxism“’. By which Fritz used the extremist language of the National Socialists against political opponents.

During the Gelsenberg affair in 1932 there were press reports, encouraged by the former Reich Finance Minister Hermann Dietrich, that Fritz Thyssen had negotiated a deal for the United Steelworks with French and Dutch investors, but that the Reich government wanted to prevent this, because it did not wish for foreign influence on the enterprise. By writing a letter to the German public, that he had ‘only explored the possibility of obtaining loans’, Thyssen ‘consciously exposed the Reich government’, writes de Taillez. The author argues that Thyssen’s statements were dismantled when a letter by Friedrich Flick to him was leaked to the Frankfurter Zeitung, which showed that Flick ‘had (rejected) Thyssen’s suggestion precisely because of the source of the money connected with it’. The Düsseldorf Volkszeitung newspaper reacted by calling Thyssen ‘unpatriotic’.

At the beginning of 1932, while his brother Heinrich bought Villa Favorita in Lugano, Fritz ‘veered demonstratively towards National Socialism’. His wife had already joined the party on 01.03.1931. He would do so officially on 07.07.1933. Looking back at the Ruhrkampf, Fritz concluded, according to de Taillez, that this was ‘a preliminary for the national socialist body of thought of the new Germany’: ‘In contrast to 1932 now it is not just the Ruhr area standing firm, but the whole of Germany will go the path that the “Führer“ is prescribing. The shattering of Marxism in the country was only down to Hitler, the SA and the SS’ (from an article in the Kölnische Zeitung newspaper ‘Fritz Thyssen about the class struggle’, on 02.05.1933).

Thus Thyssen became a ‘media player’, who under Hitler ‘profited considerably from the abolition of the freedom of the press’, as soon nobody was allowed any longer to set anything against his verbal crudeness. Meanwhile, he led negotiations in Buenos Aires ‘with high state organs’ such as ‘General Agustin Pedro Justo, the President in power since 1932 after rigged elections’. Subsequently an Argentinian-German trade agreement, including offsetting and compensation procedures, was signed in November 1934, whereby trade between the two countries increased drastically. It seems Thyssen was trying to help form an antipole to Anglo-American economic might. But Felix de Taillez believes Fritz, utterly selfishly, was just helping construct his own ‘image’ as an ‘influential economic leader’, to bring great publicity to himself.

Not all of the South-American press was positive about Thyssen. The Argentinian Tagesblatt paper in 1934 talked about a ‘coming together of joint bankruptcies’ having taken place in 1933, when the United Steelworks were bankrupt and the Nazi party was ‘hopelessly in debt’. ‘The newspaper accused the United Steelworks under Thyssen’s leadership as chairman of the supervisory board to have carried out extensive accounting fraud.’ (from their article ‘Business deals of a State Councillor’, dated 08.11.1934). The Cologne cultural magazine ‘Westdeutscher Scheinwerfer’ described Fritz Thyssen as an ‘autocrat’ and ‘said the main reason for the crisis at the United Steelworks was the contentious personal politics of Fritz Thyssen’. His critics in the media ‘declared Fritz Thyssen to be incapable in economic and political affairs’ and ‘made him responsible for the high losses at United Steelworks’.

It was the very thing his father August, who had no social ambition but lived entirely for his works, had warned about many years earlier. He had ensured Fritz was only head of the supervisory board, not the management board, in order to minimise the damage August was convinced Fritz would do to the company. August believed Heinrich was only marginally more adequate than Fritz to be head of the Thyssen empire (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 70).

Meanwhile, after the war, the Allies would accuse the United Steelworks of ‘consistently giving their full financial support to the militarily-minded National Socialist Party’. Loping the ball back into the allied court, Fritz Thyssen would write in 1950 ‘In my opinion, the Nuremberg trials were conducted mainly to find someone to blame for Hitler’s WAR policy. It would have been very embarrassing for the Americans to have to admit that they had supported the German rearmament from the very first, because they wished for a WAR against Russia’ (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, pages 80 and 230).

‘Remarkably’ for a man whose credibility depends on the assertion that his anti-war stance led him eventually to breaking with the Nazis, when the national socialists Wilhelm von Keppler and Kurt von Schröder collected signatures to ask Paul von Hindenburg to make Adolf Hitler Reich Chancellor, Fritz Thyssen was the ONLY member of the Ruhrlade (association of the 12 most important Ruhr industrialists that existed from 1928 to 1939) to sign. In his dealings with other industrialists he could be gruff and rude. He warned colleagues to be ‘disciplined’, especially those who he thought were being ‘liberalistic’. People such as Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, who strove against Hitler as long as he could and who, like Richard Freudenberg and many others, only surrendered to national socialism once it had been installed, as a dictatorship, with the help of the Thyssens and their associates. According to de Taillez ‘(Thyssen) threatened possible interferers citing his new influence on the state organs in charge’, i.e. he told them he would report them to Hermann Göring.

This is an admission of extremely overbearing Thyssen behaviour issued by the Thyssen complex as official historiography, which, as such, really is remarkable.

* * *

And it does not stop there. Fritz Thyssen also threatened catholic priests, who were normally his allies. In March 1933, for instance, he let it be known to Cardinal Schulte that his family would not take part in any more church services ‘as long as the unjust treatment of the Führer & members of the Nazi party endured’. He took part in sociological special meetings in Maria Laach under the Abbott Ildefons Herwegen and the circle of ‘anti-democratic rightwing catholics’, who, according to de Taillez, were ‘annexable by the national socialists’. These were ‘against the enlightenment, universal human rights, democracy, liberalism, socialism, communism, decidedly anti-semitic’ and in favour of an ‘authoritarian corporatism’. They were trying to develop a ‘Reich Theology’, ‘supported by the association of catholic academics’.

Reminding us once again that it was the professions, such as the legal community, who took particularly early and enthusiastically to the Nazi ideology.

Despite all this threatening behaviour, Felix de Taillez alleges – not very convincingly – that Fritz Thyssen interpreted national socialism ‘in a conservative manner’. Apparently, he saw it as the ‘renaissance of a lost State and of the Volksgemeinschaft (Peoples Community)’. He writes that for Thyssen, national socialism was not so much an ideology as a ‘HEROIC FORCE’, whereby a ‘class of people underpinning the state’ had been resurrected, who had taken up the ‘battle against the gravediggers of the state’. – This is reminiscent of the intrumentalising slogans, used by proto-fascist veterans’ associations as mentioned by Angel Alcalde -. But in the same paragraph, Fritz Thyssen then divulged his elitist understanding of his role within national socialism, when he said that one would, however, take away ‘the dignity and primacy of this class of people if one were to try and lift up 64 million people into the same dignity through ideological propaganda’.

For the Rheinische Zeitung newspaper, this meant that Thyssen was a fascist, but no ‘roister Nazi’. In reality it meant that he saw himself and his family as part of the State, but not as part of the Volksgemeinschaft (Peoples’ Community), which he thought should be kept subservient to himself and his associates.

It sounds less like a conservative and more like a FEUDAL understanding of national socialism.

As the dictatorship gathered momentum, the Gauleiter of Essen, Josef Terboven, asked Rudolf Hess in a letter ‘to have the “Führer“ name Thyssen as politico-economic plenipotentiary for the Ruhr area and to have his position endowed with unconditional authority’. There seems to have been a power triangle of Hermann Göring, Gauleiter Terboven and Fritz Thyssen, whose media voice piece was the National-Zeitung newspaper. According to de Taillez, Thyssen took part in the Nuremberg party rallies. He was a member of the Central Committee of the Reichsbank, of the Academy of German Law and of the Expert Committee on Questions of Population and Racial Policy (see also here). By 1938, Fritz had assembled so many supervisory board mandates for himself, ‘that he was positioned as an individual in the centre of a network of the Reich economic elite, on third place after the chairman of the United Steelworks, Albert Vögler, and the bank director of Berliner Handelsgesellschaft, Wilhelm Koeppel’.

* * *

The groundbreaking thesis of Felix de Taillez is that it took a long time for Thyssen to break with the Nazis: ‘The assertions uttered by him and by his associates during the 1948 denazification proceedings that he had already turned away demonstratively during the 1930s (thus appear) as no more than pretextual, easy to see through, defensive attempts.’ Even in 1936, de Taillez writes, Thyssen still defended Hitler at the Industry Club in Düsseldorf ‘almost manically’, using quotations from “Mein Kampf“. In the same year, he showed himself to be ‘unteachable’, as he accused those who saw the Nazis’ armaments policies as harbingers of war, of being wrong. According to Thyssen, ‘it was only owing to Hitler that Germany was once again seen internationally as an equal partner’. Gottfried Niedhart and the Perlentaucher (elitist culture blog) have taken up joyfully the interpretation that Fritz Thyssen ‘was not at all the powerful man behind Hitler’, but only ‘blinded’ by him, and that ‘he really seems to have thought that the rearmament did not serve the preparation of war, but the goal of “becoming capable of forming alliances“’.

But why should one believe that a man, whose views were otherwise so changeable and untrustworthy, should have seen clearly and been truthful in his anti-war stance, which just so happens to hit at the central agony of the German nation (namely the question of their responsibility for the Nazis’ war and its horrors)? Does it not, rather, seem like yet another attempt at obscuring the Thyssens’ long-lasting support of the National Socialist regime? Particularly as his alleged anti-war stance was central also to the Thyssens’ ability of regaining their assets from the allies after the war.

And why, if Fritz knew, as he wrote in 1950, that the Americans wanted to rearm Germany to go to war with Russia, did he not break away from this evil alliance earlier on?! Because he too was for a war against the Soviet Union after all? Or because it was more important for him to reap the economic benefits than to take a moral stance? And if so, why are these official Thyssen biographers overall still alleging his flight from Germany, when it finally came, to have been a moral stance, rather than one of convenience, when according to de Taillez, he had missed out so many earlier opportunities at opposing Hitler’s plans?

In the words of de Taillez, when Hermann Göring declared the mobilisation of the wartime economy in the summer of 1938, Thyssen propagated ‘this propaganda in the media through his clear avowal of allegiance to the Four-Year-Plan’. In February 1939 he was named by Walther Funk (who was a client of the August Thyssen Bank, see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 87) as a Leader of the Wartime Economy. The assertions presented at the denazification trial that Thyssen had harboured ‘serious thoughts of subversion’ and had been in contact with resistance circles is described by de Taillez as ‘idle’, because ‘reliable sources do not exist’. Rather, de Taillez testifies to Thyssen remaining absolutely ‘inactive’ until November 1939, i.e. until two months after the start of the war. An assertion that ‘Thyssen proposed a close cooperation between industry and the army to General von Kluge after the November pogrom of 1938, in order to put an end to Nazi politics’ is clarified by him thus: ‘based on the situation with the sources, it is more than questionable, whether such a plan existed at all’.

Felix de Taillez thus dismantles the so far, in his own words, ‘successful reframing’ of Fritz Thyssen in an ‘image of an extraordinarily early “fanatical opponent“ of National Socialism, who was already active in the resistance in 1936’. (This being an image issued to the public from 1948 onwards by Thyssen’s solicitor and PR-advisor, Robert Ellscheid (see also here)).

And that is truly ‘remarkable’!

* * *

According to de Taillez, following Fritz Thyssen’s flight to Switzerland in September 1939, the English press reported that an international arrest warrant had been issued against him for ‘theft, embezzlement, tax evasion and contraventions against German currency restrictions’. Thyssen, however, threatened Hitler with precisely this international public opinion, while simultaneously presenting himself as a ‘proud’ German ‘with every fibre of his being’. He said he wanted to show ‘the innocence of the “German nation“ concerning recent developments’, while at the same time saying that ‘the German people had shown in the inter-war years that it was „incapable of adjusting itself to democratic institutions“’. (Even during his denazification proceeding in 1948 ‘Thyssen continued to ascertain his view that democracy was not a form of government suitable to Germany’!).

De Taillez qualifies his attitude as being ‘naive’…. ‘Schizophrenic’ and ‘impudent’ would be more adequate adjectives from our point of view. It is typical for Thyssen’s belief in his own omnipotence, that he seemed to think that the course of a war, that had been planned by such a long hand, could be changed by a few of his statements. The fact that his brother Heinrich had managed so elegantly, through his Hungarian nationality, and his secure, comfortable domicile in Switzerland, to keep out of public politics, while still enjoying all the financial rewards the Thyssen enterprises were reaping from the war, must have made Fritz very angry. This vexation might even have been one trigger for his flight. And so he showed no consideration for Heinrich’s standstill agreement with the Swiss authorities (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 103) which he endangered by his noisy flight to Switzerland.

De Taillez then explains that Fritz Thyssen, via ‘secret channels’, ‘got in touch with former Chancellor Joseph Wirth and western agents’ and thus ‘became, in a certain way, a part of Wirth’s attempts at sounding out France and England’. But then, he says, General Halder, who had been ‘until that time, head of the secret military opposition to the Third Reich’, ‘buckled at the beginning of 1940’. According to de Taillez, the French secret service, however, assumed ‘that Fritz Thyssen was the head of a far-reaching secret organisation being built up in Switzerland by Germany, in order to undermine the influence of the French and the British in Europe’. At the same time, de Taillez believes that ‘under normal circumstances, the entry of Thyssen into France during the war would have been refused. It was his luck that he had been able to convince the French secret service in Switzerland that he held important information and assessments, which would be useful to the allies in their fight against the Third Reich’.

It was always typical for the ultra-rich Thyssens to make themselves look important with everyone that mattered. Only this time, it was about war. Any kind of allegiance was never at the forefront of their mind. The Thyssens were transnational and committed to no single nation – only to themselves alone.

This fact can be gaged from the book ‘I Paid Hitler’, which Fritz Thyssen elaborated together with Emery Reves in 1940 and which was published by the latter in 1941 in London and New York (see also here). According to de Taillez, since 1937 Reves also worked with Winston Churchill. He writes that in 1940 Churchill ‘commissioned (Reves) with building up the british propaganda apparatus in North and South America’ (!). De Taillez continues: ‘Reves told Churchill about the central theory of Fritz Thyssen for the reimplementation of peace in Europe, which would soon be proclaimed publicly: the partition of Germany’ – namely into ‘a protestant Eastern Germany and a catholic Western German under a Wittelsbach’. Churchill is said to have passed on these views to his secret service advisor Major Desmond Morton – although one could have one’s doubts about how much of this was actually a direct quote from Thyssen and how much might be ascribed to British propaganda (!)…

The fact that Fritz Thyssen might also sometimes have ‘consciously spoken the untruth’ (i.e. that he sometimes lied) is a suggestion that Felix de Taillez floats in connection with Thyssen’s statements after the war concerning the creation of ‘I Paid Hitler’. It is a tinge of honesty, of openness that has also to do with „honour“ after all, and which has been missing from so many of the statements made by Thyssens and their self-proclaimed official biographers in the past. While Thyssen and his lawyers distanced themselves from the book, Reves confirmed to the denazification court that all of the book had been dictated by Thyssen and that two thirds of it had been proof-read by him. Reves rejected the idea of being a ghostwriter and described himself as publisher and press agent. He also argued that Anita Zichy-Thyssen had repeatedly thanked him for his publishing the book. To this day Anita’s descendants in South America praise the book and slander anyone critical of Fritz Thyssen (see here).

* * *

De Taillez records that following his being taken into custody by the Allies in 1945, Fritz Thyssen ‘was presented in the British and US-American weekly newsreels as an alleged war criminal’. Then, presumably in order to explain this, in his view, mistaken stance, he alledges: ‘apparently the Americans were still having difficulties in assessing the Thyssen case in a consistent way, as well as in their coordination with the German authorities’. This blocks out the fact that the Thyssen case was fraught because the allies could not access and question Heinrich in his Swiss safehaven, and because there were discrepancies between the British and the American views of how the Thyssens should be dealt with (in general, the British were much more in favour of their punishment). Wilhelmus Groenendijk, who was part of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Group finance division from 1957 to 1986 told us: ‘BOTH Heinrich and Fritz were listed as war criminals. But from the Netherlands, we managed to get their names brought further down and down on that list, until we were able to claim that the assets were in fact allied property’ – and therefore could not possibly be seen as having abetted the German war effort (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, p. 188).

De Taillez summarises for Fritz Thyssen that ‘despite considerable differences (…) he arranged himself with the Third Reich for a long time, because there was a basis of common ground’, namely the ideal of the authoritarian state, the disempowerment of the socialist workers movement and the revisionist policies. To this was added the prospect of profit increases in the steel industry. He describes that ‘the former Reich Chancellor (Heinrich) Brüning declared in writing (during the post-war denazification proceedings against Fritz Thyssen) that financing by foreign powers was decisive for Hitler’s ascent to power’. And yet various authors of this series, including de Taillez alledge that this is nothing more than a conspiracy theory. Notwithstanding, de Taillez makes the remarkable assertion that ‘the often polarising statements made by Fritz Thyssen were judged more positively in the anglo-american media, which is the most powerful media in the world, until 1933, than by the german public’ – which would of course indicate that, contrary to what is said today, there was indeed support for the German move to the extreme right in Great Britain and the United States after all.

De Taillez describes Fritz much more intimately than he does Heinrich, namely as absurd, agitating, ambivalent, influential, almost manic, polarising, divorced from reality, controversial, sophomoric, unteachable, unreasonable, unclear, a troublemaker, NONSENSICAL, incoherent, cynical, and, in a description by thirds, of having a ‘more than peculiar manner’. Many of these characteristics certainly applied to Heinrich also, because they went back not least to the greedy luxury of the family and its resulting, hubristic mannerisms. Only, Heinrich was more intelligent than Fritz and he knew in particular that one can camouflage oneself much better within a certain seclusion, especially when one is in truth even more unscrupulous than his vociferous brother.

Felix de Taillez’s colleague Jan Schleusener (‘The Expropriation of Fritz Thyssen’), rates Fritz Thyssen as a hero: he was, says Schleusener, ‘the only delegate of the Reichstag who raised objections to the launching of the war’, which reminds one of Thomas Rother’s equally unsuitable statement whereby Thyssen was ‘the only industrialist in Germany not to profit from Hitler’s war. According to de Taillez, it appears that Fritz Thyssen admitted one single time, towards Norman Cousins, ‘that he felt co-responsible for national socialism, because of his financial support of Hitler IN THE LATE 1920s’. But at the same time, Cousin noticed that Thyssen ‘did not mention the many crimes committed since 1933, the political murders, the destruction of the bourgeois freedoms and the persecution of the Jews as decisive motives for his break with national socialism’. As far as Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza is concerned, not a single statement at all concerning these topics has been handed down.

This is to be weighed up when assessing whether the alleged heroical, anti-national socialist, anti-war stance of the Thyssens was real, or whether these were exonerations issued on behalf of ruthless war opportunists (/criminals – as they must have known Hitler’s war was to be one of annihiliation) by their sycophantic underlings to ensure their bosses would not suffer any retribution.

The outstanding contribution of this book, meanwhile, is in its explanation of the utterly elitist perspective from which the Thyssens saw their role within National Socialism. So far, it is the only volume to have been reviewed, not only in academic circles, but also by a major German newspaper.

|

|

An honest German view (photo copyright: Lizas Welt – internet:lizaswelt.net/2011/02/28/volksgemeinschaft-gegen-rechts/) |

Tags: 1930 Munich Exhibition, Academy of German Law, accounting fraud, Adolf Hitler, Agustin Pedro Justo, Albert Vögler, allegiance, Alsace-Lorraine, Amelie Thyssen, Angel Alcalde, anglo-american media, Anita Zichy-Thyssen, anti-democratic rightwing catholics, anti-war stance, Anton Apold, Argentina, Argentinian Journal, Argentinian-German trade agreement, Art, art collecting, art museum, association of catholic academics, Association of Frontline Soldiers, Aufarbeitung, August Thyssen, August Thyssen Bank, Austrian Federal Monuments Office, Austrian throne, Austrian-Alpine Mining Company, Austro-fascist home guard militias, authoritarian corporatism, autocrat, Bavarian County Parliament, Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Berlin, Berliner Handelsgesellschaft, bourgeois educational mandate, Brazil, British propaganda, Buenos Aires, Burgenland, Burgenland County Government, camouflage, capital flight, Cardinal Schulte, Central Committee of the Reichsbank, Christopher Neumaier, Cologne, Communism, Compania Industrial & Mercantil Thyssen Limitada, compensation procedures, concentration camp, conspiracy theory, contraventions against German currency restrictions, customs duties, democracy, democratic institutions, denazification proceedings, destruction of the bourgeois freedoms, Deutschnationale Volkspartei, dictatorship, dishonest business practices, domicile in Switzerland, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf Peoples Paper, economic crime, Eduard von der Heydt, embezzlement, Emery Reves, enlightenment, Estancia Don Roberto Lavaisse, exhibition catalogue, Expert Committee on Questions of Population and Racial Policy, fakes, false attributions, fascist, Felix de Taillez, Ferdinand de Brinon, feudal, Financial Times Weekend Magazine, financing by foreign powers, First World War, flight, Forced Labour, Foreign Office, foreign organisation of the Nazi party, Four-Year-Plan, Francesca Habsburg, Frankfurter Zeitung, French secret service, Friedrich Flick, Friedrich Grimm, Friedrich Winkler, Fritz Thyssen, Fritz Thyssen Foundation, Gauleiter of Essen, Gelsenberg affair, General Halder, General von Kluge, Georg Thyssen-Bornemisza, George Mosse, German compensation payments for war damages, German counter-intelligence service, German cultural goods, German foreign politics, German government, German history, German nation, German national identity, German national unification, German passport, German Patriotic Party, German people, German rearmament, German war effort, German-Overseas Trading Company of the Thyssen Works, Germanness, Germany, ghostwriter, global financial player, Gottfried Niedhart, Great Britain, guilt, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Hamborn, Hans Heinrich ('Heini') Thyssen, Harald Wixforth, Harzburger Front, Heini Thyssen, Heinrich Thyssen, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Henry Ashby Turner, Hermann Dietrich, Hermann Göring, hero, Hitler's ascent to power, Hitler's war policy, Hohenzollern, Holland, honesty, honour, horse racing, Hungarian nationality, Hungarianness, Hungary, I Paid Hitler, ideological propaganda, Ildefons Herwegen, Image, Industry Club, influential economic leader, international arrest warrant, international banks, international financial speculations, Italy, Jan Schleusener, Johannes Gramlich, Jose Felix Uriburu, Josef Terboven, Josef Thyssen, Joseph Wirth, journalists, Krupp AG, Kurt von Schröder, La Plata newspaper, Leader of the Wartime Economy, liberalism, London, Ludwig Maximillian University, Lugano, Madrid, Major Desmond Morton, Maria Laach, Marxism, media, media player, media scandal, Mein Kampf, militarism, mobilisation of the wartime economy, Mülheim, Munich, Munich Pinakothek, Napoleon's art theft, nation, national socialism, National Socialist Party, National Socialist regime, National-Zeitung newspaper, nationalism, Nazi banker, Nazi crimes, Nazi ideology, Nazi Party, Nazi perpetrators, Nazis Armaments Policies, New York, New York Times, Niels Löffelbein, Norman Cousins, November pogrom, Nuremberg Trials, occupation of the Ruhr, offsetting, ore freight traffic, Ottoman Empire, paintings, participative management, partition of Germany, party state, patriotic movement of the Ruhr, Paul von Hindenburg, Peoples Community, Perlentaucher, persecution of the Jews, PR-advisor, press agent, private banking, private economy, propaganda, propaganda in favour of Germany, public relations, publisher, radical nationalism, radicalisation, Rechnitz Castle, Reich Chancellor, Reich Chancellor (Heinrich) Brüning, Reich economic elite, Reich Finance Minister, Reich Theology, Reichstag, resistance circles, responsibility, Rheinische Zeitung, Rhenania-Westphalia, Rhenanian Republic, Richard Freudenberg, Robert Ellscheid, Robert Lehr, Roberto van Aken, Rohoncz, Rohoncz Castle Collection, roister Nazi, Rothschild, Rotterdam, Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor, royal family, royal rota, Rudolf Buttmann, Rudolf Heinemann, Rudolf Hess, Ruhr coal, Ruhr industrialist, Ruhr Protection Association, Ruhrkampf, SA, Second World War, shipping company, Simone Derix, social partnership, Socialism, South America, spin, spirit of the worker, sponsorship, SS, State Councillor, state-sponsored history, Steel Helmet, Stephan Wegener, strategy of political action, submarines, Swiss customs authorities, Switzerland, tax evasion, The Expropriation of Fritz Thyssen, The Thyssen Art Macabre, The Thyssens as Art Collectors, theft, Third Reich, Thomas Rother, Thyssen AG, Thyssen Bornemisza Group, Thyssen complex, Thyssen family mythological reputation, Thyssen Industrial History Foundation, Thyssen manipulation of public perception, Thyssen manipulations, Thyssen myths, Thyssen-Bornemisza complex, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Thyssen-Lametal S.A., ThyssenKrupp, ThyssenKrupp AG, Times of London, traffic of raw materials, transnational, ultra-rich, unions, United States, United Steelworks, universal human rights, University of the German Armed Forces, Versailles Peace Treaty, Villa Favorita, Volksgemeinschaft, Vorwärts, Vulcaan, Walther Funk, war, war against Russia, war criminal, war opportunists, weapons manufacturer, Weimar Republic, Westdeutscher Scheinwerfer, Wilhelm Koeppel, Wilhelm von Keppler, Wilhelmus Groenendijk, Winston Churchill, Wittelsbah, Workers and Soldiers Council, Zurich

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Art, Thyssen Corporate, Thyssen Family Comments Off on Book Review: Thyssen in the 20th Century – Volume 6: ‘Two Burghers’ Lives in the Public Eye: The Brothers Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’, by Felix de Taillez, published by Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn, 2017

Monday, March 5th, 2018

| Reviewing this book is a huge aggravation to us, as so much of it has been derived from our groundbreaking work on the Thyssens, published a decade earlier, for which the author grants us not a single credit. It is surprising that Simone Derix does not have the respect for professional ethics to acknowledge our historiographic contribution; especially since she stated in a 2009 conference that non-academic works, whilst creating feelings of fear amongst academics of losing their prerogative to interpret history, are taking on increasing importance.

Ms Derix herself is not the fearful type of course, though somewhat hypocritical. She appears to be preemptively obedient and committed to pleasing her presumably partisan paymasters, in the form of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. Alas, she is clearly not the smartest person either; writing, for instance, that Heinrich Lübke, Director of the August Thyssen Bank (he died in 1962), was the same Heinrich Lübke who was President of Germany (in that position until 1969).

But Ms Derix’s intellectual shortcomings are much more serious than simple factual errors, which should, in any case, have been picked up by at least one of her two associate writers, three project leaders, four academic mentors and six research assistants. She is in all seriousness trying to convince us that research into the lives of wealthy persons is a brand new branch of academia, and that she is its most illustrious, pioneering proponent. Does she not know that recorded history has traditionally been by the rich, of the rich and for the rich only? Has she forgotten that even basic reading and writing were privileges of the few until some hundred and fifty years ago?

At the same time, contrary to us, Derix does not appear to have had any first hand experience of exceptionally rich people at all, particularly Thyssens. Her sponsorship, earlier in her studies, by the well-endowed Gerda Henkel Foundation, was presumably an equally ‘arm’s length’ relationship. Rich people only mix with rich people, and unless Derix got paid by the word, there is no evidence that she ever in any way qualified for serious comment on their modus operandi.

What is new, of course, is that feudalism has been swept away and replaced by democratic societies, where knowledge is broadly accessible and equality before the law is paramount. Yes, her assertion that super-rich people’s archives are difficult to access is true. They only ever want you to know glorious things about them and keep the realities cloaked behind their outstanding wealth. To suggest that this series is being issued because the Thyssens have suddenly decided to engage in an exercise of honesty, generously letting official historians browse their most private documents, however, is ludicrous. The only reason why Simone Derix is revealing some controversial facts about the Thyssens is because we already revealed them. The difference is that she repackages our evidence in decidedly positive terms, so as to comply with the series’ overall damage limitation program.

Thus, Derix seems to believe she can run with the fox and hunt with the hounds; a balancing act made considerably easier by her pronouncement, early on, that any considerations of ethics or morality are to be categorically excluded from her study. The fact that the Thyssens camouflaged their German companies (including those manufacturing weapons and using forced labour) behind international strawmen, with the benefit of facilitating the large-scale evasion of German taxes, is re-branded by Derix as being a misleading description ‘made from a state perspective’ and which ‘tried to establish a desired order rather than depict an already existing order’. As if ‘the state’, as we democrats understand it, is some kind of devious entity that needs fending off, rather than the collective support mechanism of all equal, law-abiding citizens.

It is just one of the many statements that appears to show how much the arguably authoritarian mindset of her sponsors may have rubbed off on her. The fact that academics employed by publicly funded universities should be used thus as PR-agents for the self-serving entities that are the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the Thyssen Industrial History Foundation and the ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archive is highly questionable by any standards, but particularly by supposedly academic ones. Especially when they claim to be independent.

****************

In Derix’s world, the Thyssens are still (!) mostly referred to as ‘victims’, ‘(tax) refugees’, ‘dispossessed’ and ‘disenfranchised’, even if she admits briefly, once or twice in 500 pages, that ‘in the long-term it seems that they were able always to secure their assets and keep them available for their own personal needs’.

As far as the Thyssens’ involvement with National Socialism is concerned, she calls them ‘entangled’ in it, ‘related’ to it, being ‘present’ in it and ‘living in it’. With two or three exceptions they are never properly described as the active, profiting contributors to the existence and aims of the regime. Rather, as in volume 2 (‘Forced Labour at Thyssen’), the blame is again largely transferred to their managers. This is very convenient for the Thyssens, as the families of these men do not have the resources to finance counter-histories to clear their loved ones’ names.

But for Simone Derix to say that ‘from the perspective of nation states these (Thyssen managers) had to appear to be hoodlums’ really oversteps the boundaries of fair comment. The outrageousnness of her allegation is compounded by the fact that she fails to quote evidence, as reproduced in our book, showing that allied investigators made clear reference to the Thyssens themselves being the real perpetrators and obfuscators.

Yet still, Derix purports to be invoking German greatness, honour and patriotism in her quest for Thyssen gloss. She alleges bombastically that the mausoleum at Landsberg Castle in Mülheim-Kettwig ‘guarantees (the family’s) presence and attachment to the Ruhr’ and that there is an ‘indissoluble connection between the Thyssen family, their enterprises, the region and their catholic faith’. But she fails to properly range them alongside the industrialist families of Krupp, Quandt, Siemens and Bosch, preferring to surround their name hyperbolically with those of the Bismarck, Hohenzollern, Thurn und Taxis and Wittelsbach ruling dynasties.

In reality, many Thyssen heirs chose to turn their backs on Germany and live transnational lives abroad. Their mausoleum is not even accessible to the general public. Contrary to what Derix implies, the iconic name that engenders such a strong feeling of allegiance in Germany is that of the public Thyssen (now ThyssenKrupp) company alone, as one of the main national employers. This has nothing whatsoever to do with any respect for the descendants of the formidable August Thyssen, most of whom are, for reason of their chosen absence, completely unknown in the country.

****************

In this context, it is indicative that Simone Derix categorises the Thyssens as ‘old money’, as well as ‘working rich people’. But while in the early 19th century Friedrich Thyssen was already a banker, it was only his sons August (75% share) and Josef (25% share), from 1871 onwards (and with the ensuing profits from the two world wars) who created through their relentless work, and that of their employees and workers, the enormous Thyssen fortune. Their equal was never seen again in subsequent Thyssen generations.

Thus the Thyssens became ‘ultra-rich’ and were completely set apart from the established aristocratic-bourgeois upper class. They could hardly be called ‘old money’ and neither could their heirs, despite trying everything in their power to adopt the trappings of the aristocracy (which beggars the question why volume 6 of the series is called ‘Fritz and Heinrich Thyssen – Two bourgeois lives in the public eye’). This included marrying into the Hungarian, increasingly faux aristocracy, whereby, even Derix has to admit, by the 1920s every fifth Hungarian citizen pretended to be an aristocrat.

The line of Bornemiszas, for instance, which Heinrich married into, were not the old ‘ruling dynastic line’ that Derix still pretends they were. The Thyssen-Bornemiszas came to be connected with the Dutch royals not because Heinrich’s wife Margit was such a (self-styled) ‘success’ at court, but because the Thyssens had important business interests in that country. Thus Heinrich became a banker to the Dutch royal household, as well as a personal friend of Queen Wilhelmina’s husband Prince Hendrik.

The truth is: apart from such money-orientated connections, neither the German nor the English or any other European nobility welcomed these parvenus into their immediate ranks (religion too played a role, of course, as the Thyssens were and are catholics). Until, that is, social conventions had moved on enough by the 1930s and their daughters were able to marry into the truly old Hungarian dynasties of Batthyany and Zichy.

But until that time, based on their outstanding wealth, this did not stop the brothers from adopting many of the domains of grandeur for themselves. Fritz Thyssen, according to Derix, even spent his time in the early 1900s importing horses from England, introducing English fox hunting to Germany and owning a pack of staghounds. He also had his servant quarters built lower down from his own in his new country seat, specifically to signal class distinction.

These are indeed remarkable new revelations showing that the traditional image put out by the Thyssen organisation of bad cop German, ‘temporarily’ fascist industrialist Fritz Thyssen, good cop Hungarian ‘nobleman’ Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza is even more misleading than we always thought.

****************

Truly lamentable are Derix’s attempts to portray Fritz Thyssen as a devout, christian peacenik and centrist party member. And so are her lengthy contortions in presenting Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza as the perfectly assimilated Hungarian country squire. She does, however, report that Heinrich’s wife had stated he did not speak a word of the language, which does not stop Felix de Taillez in volume 6 writing that he did speak Hungarian. ‘If you can’t beat them, confuse them’ was Heini Thyssen’s motto. Clearly, it has also become the motto of these Thyssen-financed academics.

Meanwhile, Derix’s book is the first work supported by the Thyssen organisation to confirm that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza did retain his German (then Prussian) citizenship. She also does venture to state that his adoption of the Hungarian nationality ‘might’ have been ‘strategic’. But these gems of truthfulness are swamped under the fountains of her gushing propaganda designed to make the second generation Thyssens look better than they were. This includes her development of August Junior’s role from black sheep of the family to committed businessman.

On the other hand, the author still fails to explain any business-related details on the much more important Heinrich Thyssen’s life in England at the turn of the century (cues: banking and diplomacy). How exactly did the family come to be closely acquainted with the likes of Henry Mowbray Howard (British liaison officer at the French Naval Ministry) or Guy L’Estrange Ewen (special envoy to the British royals)? A huge chance of genuine transparency was wasted here.

Derix also fails to draw attention to the fact that the August Thyssen and Josef Thyssen branches of the family developed in very different ways. August’s heirs exploited, left and betrayed Germany and were decidedly ‘nouveau riche’, except for Heinrich’s son Heini Thyssen-Bornemisza and his son Georg Thyssen, who really did involve themselves in the management of their companies.

By contrast, Josef’s heirs Hans and Julius Thyssen stayed in Germany (respectively were prepared to return there in the 1930s from Switzerland when foreign exchange restrictions came into force), paid their taxes, worked in the Thyssen Konzern before selling out in the 1940s, pooling their resources and adopting careers in the professions. Only the Josef Thyssen side of the family is listed in the German Manager Magazine Rich List; but for unexplained reasons Derix leaves these truly ‘working rich’ Thyssens largely unmentioned in her book.

****************

Fortunately, Derix does not concentrate all her efforts in creative fiction and plagiarisation, but manages to provide at least some substantive politico-economic facts as well. So she reveals that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza was a member of the supervisory board of the United Steelworks of Düsseldorf until 1933, i.e. until after Adolf Hitler’s assumption of power. This, combined with her statement that ‘Heinrich seems to have orientated himself towards Berlin on a permanent basis as early as 1927/8 (from Scheveningen in The Netherlands)’ pokes a hole in one of the major Thyssen convenience legends, that of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza having had his main residence in neutral Switzerland from 1932 onwards (i.e. conveniently from before Hitler’ assumption of power; having ‘left Germany just in time’); though this does not stop Derix from subsequently repeating that fallacy just the same (- ‘If you can’t beat them, confuse them’-).

Fact is that, despite buying Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland in 1932, Heinrich Thyssen continued to spend the largest amounts of his time living a hotel life in a permanent suite in Berlin and elsewhere and also kept a main residence in Holland (where Heini Thyssen grew up almost alone, except for the staff). His Ticino lawyer Roberto van Aken had to remind him in 1936 that he still had not applied for permanent residency in Switzerland. It was not until November 1937 that Heinrich Thyssen and his wife Gunhilde received their Swiss foreigner passes (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, page 116).

Derix also readjusts the old Thyssen myth that Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza went their separate ways in business as soon as they inherited from their father, who died in 1926. We always said that the two brothers remained strongly interlinked until well into the second half of the 20th century. And hey presto, here we have Simone Derix alleging now that ‘historians so far have always assumed that the separation had been concluded by 1936’. She adds ‘despite all attempts at separating the shares of Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, the fortunes of Fritz and Heinrich remained interlocked (regulated contractually) well into the time after the second world war’.

But it is her next sentence that most infuriates: ‘Obviously it was very difficult for outsiders to recognise this connection’. The truth of the matter is that the situation was opaque because the Thyssens and their organisation went to extraordinary lengths and did everything in their power to obfuscate matters, particularly as it meant hiding Fritz Thyssen’s and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s joint involvement in supporting the Nazi regime.

****************