|

Article by Sacha Batthyany in ‘Das Magazin’, Switzerland, 11.12.2009.

Translation copyright Caroline Schmitz.

http://dasmagazin.ch/index.php/ein-schreckliches-geheimnis/

(Note DL: Sacha approached us for assistance in researching this article and we granted him access to photographs and documents).

‘The Terrible Secret

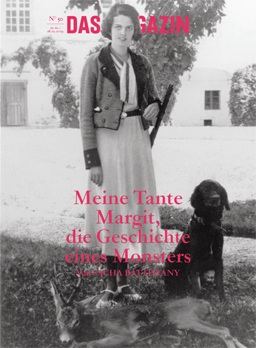

During a party in the Austrian village of Rechnitz shortly before the end of the war, 180 Jews were murdered. The hostess was Margit Batthyany-Thyssen, the author’s great-aunt. A family story.

I am standing in front of Aunt Margit’s grave and am trying to remember her face, but I can’t. The wind is taking the last leaves off the trees and Lake Lugano appears cold and grim. When I think of Aunt Margit’s face, I only ever see her tongue.

It is a simple grave, Castagnola cemetery, at the foot of Monte Bre – just a simple granite plate, although Margit was one of the richest women in Europe, and modesty was not one of her virtues. “21. June 1911 – 15. September 1989 Margit Batthyany-Thyssen”. Somebody has put fresh chrysanthemums there and the earth in the pot is fresh too.

When I was a child we used to go eating out with her twice a year, always at Hotel Dolder in Zurich, my father would already swear on the way there and smoke one cigarette after another in our Opel, my mother would comb my hair with a plastic comb.

We called her Aunt Margit, never Margit, as if Aunt was a title, in my memory she wears suits, buttoned right up to her throat and silk foulards with equestrian designs. She is tall, a huge upper body on thin legs, her crocodile leather bag is bordeaux red with golden clips, and when she talks, about the deer rutting season or about ship cruises in the Aegean Sea, then she moves the tip of her tongue out of her mouth between sentences, like a lizard, she does this like other people constantly play with their hair or touch their noses. I sit as far away from her as possible, Aunt Margit hated children, and while I very slowly pick at my shredded calf’s liver, I look over to her again and again. I want to see that tongue.

After her death we only seldom spoke of her, my memory of those lunches faded away, until in 2007 I read about this Austrian village for the first time. Rechnitz. About a party. About a massacre. About 180 dead Jews, who had to undress themselves first before they were shot, so that their bodies would rot faster. And Aunt Margit?

She was right in the middle of it all.

I call my father and ask him, whether he knew about it. I can hear how he uncorks a bottle of wine and I visualise him, sitting on this old sofa which I like so much, in his flat in Budapest. “Margit had an affair with a Nazi called Joachim Oldenburg, that was talked about within the family”. In the newspaper they say she organised a party and as a high point, ‘for deserts’, lured 180 Jews into a stable and handed out weapons. Everybody was pissed out of their brains. All were allowed to shoot. Margit too. That’s what an English journalist, David Litchfield, is alleging. He calls her “Killer Countess” in the Independent. In FAZ she is called “Hostess from Hell” and Bild-Zeitung is writing: ‘Thyssen-Countess had 200 Jews shot at Nazi-party”.

“That’s nonsense. There was a crime, but I really don’t think that Margit had anything to do with it. She was a monster, but she wasn’t capable of that”.

Where was Margit’s husband, Ivan? Was he at the party too?

“Ivan was my uncle, your grand-father’s brother. While Margit was spending her time in her castle in Rechnitz with Nazis, Ivan was in Hungary. Their marriage was a disaster from the start. She was the German Thyssen-Billionairess and Ivan was the impoverished Hungarian Count.”

Why was Margit a monster?

“Those are old stories”.

Shortly after the war there were several court proceedings. When one reads the witness statements about the Rechnitz massacre, file Vg 12 Vr 2832/45, Vienna County Archive, one gets the following picture: The night of 24 to 25 March 1945 was a moonlit night. In the castle of Margit Batthyany-Thyssen in Rechnitz, Burgenland, Austro-Hungarian border, a Nazi-Gefolgschafts(followers)-party is taking place. Members of the Gestapo and local Nazi greats such as SS-Hauptscharführer Franz Podezin, Josef Muralter, Hans-Joachim Oldenburg are chatting with Hitler Youth and employees of the castle and sitting down at round tables in the small hall on the ground floor. For the National Socialists, the war is over, the Russians are already at the Danube, but this mustn’t spoil their fun. It is eight o’clock in the evening. At the same time ca. 200 Jewish slave labourers from Hungary, who were used for the construction of the south-eastern wall, a gigantic defence wall from Poland, via Slovakia, Hungary and all the way to Trieste, which was to hold up the advancing Red Army, are standing at the train station in Rechnitz. At half past nine in the evening, the haulier Franz Ostermann loads some of the Jews into his lorry and, after a short drive, hands them over to four men from the Sturmabteilung, the SA, who hand shovels to the prisoners and order them to dig an L-shaped pit.

Where are the bodies?

The first time I drive to Rechnitz, it is springtime, everything is green, the fields, the woods, the grapes on the vines are small and hard, Rechnitz is not a beautiful village: one main road with low houses left and right, which have narrow windows and net curtains you can’t see through. There is no centre, no main square, the castle, which the stinking rich German entrepreneur and art collector Heinrich Thyssen signed over to his daughter Margit, our Aunt Margit, in his will, no longer stands.

(Note DL: Heinrich signed the castle over to Margit on 08.04.1938, nine years before his death, but he continued to finance the castle’s overheads throughout the war, during which it was used by the SS and Margit).

The Russians bombed it when they entered in 1945, and the villagers plundered all the furniture, paintings, carpets.

(Note DL: The Rechnitz town historian, Dr Josef Hotwagner, who for some reason Sacha Batthyany is not mentioning in his article, despite interviewing him twice, said there is evidence that the Germans set the castle alight as they left and that some local people, who tried to put the fire out, were even shot by the departing SS. I am also extremely surprised by his allegations of plundering by the villagers. It is certainly the only time I have ever heard such an allegation. Josef Hotwagner’s father and uncle were killed by the Germans for helping families persecuted by the Nazis. Sacha also fails to mention that it was the Batthyany family who originally established the Jewish community in Rechnitz.)

Each year the Refugius association organises a memorial for the murdered Jews. At the entrance to the village, where the Kreuzstadl – a memorial monument – stands, they sing and pray, the crime must not be forgotten, dandelion flowers, the grass is ankle-high, somewhere underneath lie 180 skulls.

(Note DL: These are not just skulls. They are the remains of human beings with children and parents and loved ones).

In the witness statements from the Rechnitz proceedings, file Vg 12 Vr 2832/45, Vienna County Archive, one learns the following:

(Note DL: The Austrians were, in case you have forgotten, part of Nazi Germany. Are you in all seriousness suggesting these people, many of whom still support right-wing extremism, should under these conditions be considered a reliable source of information? Particularly, as Professor Walter Manoschek will confirm, while they still refuse access to various files relating to the atrocity?).

The Hungarian Jews dig an L-shaped pit with shovels and pick-axes, they are tired and weak, the earth is hard, in Aunt Margit’s castle people are drinking and dancing. At about 9 pm SS-Hauptscharführer Franz Podezin receives a call.

(Note DL: Why at this time of night?! Why didn’t you talk to the Jewish survivor whose details we gave you: Gavriel Livne. Or Gabor Vadasz, who lost his father and uncle in the atrocity, and whom your father may wish to visit, as he also lives in Budapest).

As the noise in the party hall is too great, he has to go into an adjoining room, the conversation lasts barely two minutes, Podezin says: “Yes, Yes!”, and he ends with the words “bloody disgrace!”.

(Note DL: This supports one of the two most popular excuses for the slaughter of Jews. The first is ‘we were only obeying orders’, the second is ‘they had typhoid, so we had to kill them to stop it spreading’).

He orders Hildegard Stadler, she is the leader of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM) (League of German Girls) and Podezin’s lover, to bring ca. ten to thirteen party guests to a room. “The Jews from the train station”, he tells them, “have contracted typhoid and have to be shot”. Nobody contradicts him. The weapons master, Karl Muhr, hands out guns and ammunition to the party guests. It is shortly after 11 pm. There are three cars waiting in the castle courtyard. Not all the people from the group fit into them, some go by foot. It is not far, after all.

(Note DL: Weapons master? This wasn’t a hunting lodge. It was a front line fort full of SS troops that was about to be overrun by the Red Army!).

“It is our duty to remember, so that it does not happen again”, says the catholic priest of Rechnitz in front of the Kreuzstadl, the memorial site, most mourners are wearing a kippah, petrol engines howl in the background, it sounds like a hundred defect lawn mowers, there is high activity on the speed arena ‘Ready to Race’, the nearby cart circuit. It is Sunday, the sun is shining. The inhabitants of Rechnitz stay away from the memorial event,

(Note DL: Were any of the Batthyanys there apart from you? Was Francesca Thyssen there? Sacha did not stay in Rechnitz, but at Bernstein Castle, originally owned by Janos Almasy, fascist sympathiser and Unity Mitford’s lover).

they eat icecream in the icecream parlour, wearing short trousers for the first time this year, only the mayor is present. Engelbert Kenyeri, a portly, friendly man, stands somewhat to one side in his best suit, locking his hands over his stomach. “Of course I would love to know where the grave is”, he tells me the next day in his office, which is much too big,

(Note DL: Too big for what? Or do you believe his status was insufficient for such an office?).

he is different from his predecessor in that he supports the Aufarbeitung of the massacre. “As long as the victims have not been found, the rumours won’t disappear”. Some people say the Jews were thrown into the artificial lake, they were cemented over a long time ago, say others, or are underneath the school’s football pitch. Each year, people with divining rods walk over the fields in zigzags and report strange vibrations. The “New York Times” has been here, so has CNN, the small village in the southern Burgenland is world-famous – but nobody comes for the dry riesling, which is produced here, everybody comes because of the mass grave, which nobody knows where it is. And the villagers keep stumm.

(Note DL: Oh, so it’s their fault, not yours and the Thyssens’. We told you the Russians had already published a full report of the atrocity and where the bodies were buried. Why do neither you nor the Austrian authorities mention this or approach them? Isn’t it interesting that it was an Austrian academic, Stefan Karner, who came back with the news to Eduard Erne that the Russians had destroyed the files?).

The search for the grave is becoming a curse for Rechnitz. In the 65 years since the crime Rechnitz has become a symbol for the way Austria has dealt with its national-socialist past. Whoever says Rechnitz, means blocking out.

(Note DL: So why are you basing yourself on their evidence?).

I call my father. I say to him, you knew that Aunt Margit was there that night, and you knew about the massacre.

“Yes”.

But you never thought that she might have had something to do with it?

“Is this an interrogation?”

I’m only asking.

“No. I never thought that there might be a connection between the party and the massacre, which is what everybody seems to be saying lately. Wait a moment”, he coughs, I can hear how he takes a cigarette out of the packet.

You smoke too much.

“How is the little one?”

She is getting her third tooth, and she is crawling. Why did you never talk to Margit about the war?

“What should I have asked her? Hey, Aunt Margit, do you want some more wine? And, by the way, Aunt Margit, did you shoot Jews?”

Yes.

“Don’t be naive. They were courtesy calls. We talked about the weather, and she sniped at family members. ‘Rotten seed’, she would say, when she spoke about the Thyssens and the Batthyanys who, according to Margit, were all off their heads. ‘Rotten seed’, that was her best saying. Can you still remember her tongue?”

Archives in Russia

The first digs took place as early as 1946, even then all the witness statements about the grave contradicted one another. There was a hand sketch by two Rechnitz villagers who were both sure to know the location: close to a small piece of wood, called the ‘Remise’, that’s where the murdered Jews were said to be buried, but they were not found. There were aerial photographs from pilots of the Royal Air Force, who flew over the area shortly after the war. A grave of that size, with its freshly moved earth, would have been spotted, but the clouds were hanging low, on that day of all days, the view was bad, the photos unusable. Twenty years later the Austrian Interior Ministry (BMI) and the Volksbund Deutscher Kriegsgräberfürsorge (VDK) (Association for the Care of German War Graves) made a fresh attempt. A certain Horst Littmann led the excavations and found the bones of eighteen corpses at the Hinternpillenacker (name of a field) close to the abattoir. But Littmann did not find the mass grave that he was looking for. What he did find, however, was an anonymous threatening letter on his car window: “If you don’t stop you will soon lie where the others lie too”. In 1990, the Institute for Prehistory and Early History at Vienna University reopened the case. Once again, all the source materials and witness statements were checked over, there were renewed excavations, Margareta Heinrich and Eduard Erne made a documentary film about them. The two film makers banged on every door in the village, they checked out old people’s homes, searched far-flung Russian archives for additional evidence and posted newspaper adverts as far away as Israel: they appealed to anybody who knew anything about the Rechnitz massacre to contact them. Please. Urgently. They researched for five years: yet again nothing. The last earth tests and geo-electrical measurements were taken in 2006, using improved technology and expensive software. Blood-sniffing dogs were also used for the first time, they found animal bones, probably from chickens.

In the witness statements on the Rechnitz proceedings, file Vg 12 Vr 2832/45, Vienna County Archives, it says: Between midnight and three o’clock in the morning the lorry entrepreneur Franz Ostermann drives a total of seven times from the train station to Kreuzstadl, with 30-40 Jews each time, whom he hands over to four SA-men. The Jews are made to undress, their clothes pile up in front of the pit, they kneel down naked on the edge of an L-shaped grave, the ground is hard, the air is cold, it is a moonlit night.

(Note DL: Why did you make no attempt to speak to Jewish survivors?).

Podezin is standing there, Oldenburg too, fanatical national socialists both of them. And they shoot the Jews in the neck. A certain Josef Muralter, nazi party member, shouts, while shooting: ‘You pigs belong into the fire. You traitors of the fatherland!’. The Jews slump and fall down into the earth hole, where they are stacked on top of one another like sardines. In the castle, people are drinking and dancing, somebody is playing an accordion, Margit is young, and she likes having fun, and she wears the most beautiful clothes out of all of them. A waiter by the name of Viktor S. notices that the guests who reappear in the hall at 3 am are gesticulating wildly, they have red faces, SS-Hauptscharführer Podezin, the presumed leader, one moment ago he was shooting women and men in the head, now he dances boisterously.

Not all of the Jews are shot that night. Eighteen are kept alive for the moment. They are given the task of closing the hole with earth. Grave digger services. Twelve hours later, on the evening of 25 March, they too are killed on the orders of Hans-Joachim Oldenburg, Margit’s lover, and buried near the abattoir at the Hinternpillenacker field. The Eighteen bodies are found in the spring of 1970 by the above mentioned Horst Littmann, exhumed and transferred to the Jewish cemetery in Graz-Wetzl.

Margit’s last evening

My second trip to Rechnitz takes place at the end of summer, the air is murky, the grapes are now red. I visit Annemarie Vitzthum on Prangergasse, she is 89 years old and possibly the last survivor who took part in Margit’s party, 65 years ago. She immerses herself in reminiscences: “I put on my very best clothes, we were sitting at round tables in the small hall on the ground floor, the Count and Countess right in the middle, Countess Margit looked like a princess, such beautiful clothes as she was wearing”. She says that men in uniform were coming in all the time, and leaving the party again, that she can’t remember their names, “it was a hurly-burly”, that’s what she told the public prosecutor as well, in 1947, when she was interrogated. “Everybody drank wine, everybody danced, I didn’t know that sort of thing, I was only a simple girl after all, only the telephone operator.” She says that she was accompanied home by a soldier at midnight and that the Countess had not left the castle by then.

(Note DL: That doesn’t mean she didn’t).

“That about the Jews”, says Mrs Vitzthum, we are eating her home-made apple cake, she says she only learned later on. Terrible. “The poor people, they say they were only bones”.

I visit Klaus Gmeiner. He was Aunt Margit’s forrester and was the last person to see her alive. Margit owned 1000 hectare of land in Rechnitz, and every year she came to hunt, deer, wild boar, small game, “she was an excellent shot, an experienced Africa-hunter”, stag antlers hang on the wall of Gmeiner’s office, “she was very happy when she killed something, a mufflon ram or a deer, she was never happier”. Gmeiner, who like so many others in the village raves about Margit, says that in all those years they never once talked about the Nazi-period. They are in awe like subjects of a queen: that she was so generous, so friendly, so religious, so beautiful, she most certainly has nothing to do with the massacre. “We were hunting”, he recalls the night before she died, “she hit the mufflon with a precisely calculated shoulder shot”. He says the animal staggered another twenty, maybe thirty paces in her direction, he remembers it very well, only then did it fall down. “We said ‘Weidmannsheil’ (‘have good sport’) to one another and drank a little glass of wine in the hunting lodge. He still remembers – and Gmeiner’s voice, normally strong and full, starts breaking up, how she was complaining that night about many people asking her constantly for money. “That was her last sentence”. The next morning she didn’t come for breakfast. Klaus Gmeiner went up, 15. September 1989, and banged on her door, 10:15 am, Margit’s eyes were closed. Heart failure.

(Note DL: You told us he confirmed the fact that people were given land and money to keep them quiet. Not because she had a big heart!).

“How was Rechnitz? Did you find out anything?”, my father asks me on the phone. He sounds tired, a few weeks ago a young dog strayed into his house, he won’t leave his side, maybe that’s why. The people in the village called me Count, it’s strange. In Switzerland many people think that Batthyany is an Indian name, so they speak to me very slowly and overly clearly on the phone. And in Burgenland they almost curtsey to me. I prefer to be Indian.

“I don’t like that behaviour either”.

Witnesses allege that Margit’s husband Ivan, your uncle, was also at the party.

“In the family, they always said that he had been in Hungary that night”.

(Note DL: This makes it sound as if you want to cast some doubt as to Ivy’s presence. If you know so much about Margit, how come Ivy is so veiled?!).

I’m starting to think that everybody is manipulating the story for their own ends. The family doesn’t want to be drawn into it and withdraws. The media want the headlines of the blood-thirsty Countess, who massacres Jews, and the inhabitants of Rechnitz want to swipe the whole thing under the carpet. For them Aunt Margit is a holy woman – whoever talks about her, starts to weep.

“And what do you want?”

(Note DL: You know what I want? I want you to say sorry for your family’s involvement and silence. To display some remorse for such a crime. Unfortunately, this reads like a text-book example of damage limitation and guilt containment).

From Hell to Heaven

My father fled Hungary together with his parents in 1956, he was 14 at the time. “I am in Budapest and I see dead horses in the street”, since I was a boy, he always started the story of his flight with this sentence, and he told it often. “With two rucksacks we cross the border into Austria and travel on from there to Switzerland”. Joining Margit and Ivan, who took them into their home, Lugano, Villa Favorita, at the foot of Monte Bre: Heaven itself. “A driver was waiting for us at the station, I am taken to a room, I feel feverish, next morning I wake up, the sun shines directly onto the bed, there are palm trees in the garden, then Ivan comes in, my uncle, he asks me whether I would like to go for a ride in his Ferrari, and I’m thinking: Am I in Heaven?”

(Note DL: And how does he think the family and friends of the 180 Jews feel?).

In the protocols of the Rechnitz proceedings, file Vg 12 Vr 2832/45, one can read: Seven people are indicted with mass murder and torture, respectively crimes against humanity. Josef Muralter, Ludwig Groll, Stefan Beigelbeck, Eduard Nicka, Franz Podezin, Hildegard Stadler, Hans-Joachim Oldenburg.

(Note DL: But not one Thyssen or Batthyany. So that’s all right then. You can all sleep easily at night).

But the proceedings stall, because the two main witnesses are murdered in 1946. The first one is Karl Muhr: weapons master at the castle. In the night of 24 March, he hands over the guns and looks into the faces of the people who later committed the crime. One year later Muhr lies dead in the woods with a bullet through his head next to his dead dog – his house goes up in flames, the cartridge, which the police found at the scene of the crime, disappears. The second one is Nikolaus Weiss: an eye witness. He survived the massacre, flees and hides with a Rechnitz family in their barn. One year later he is travelling to Lockenhaus, his car is shot at and starts skidding, Weiss is dead on the spot. Since these two lynch-law killings the people of Rechnitz live in fear of reprisals. Nobody talks. The silence lasts to this day.

My father owes Margit a lot. She made it possible for him and his family to flee, she paid for his boarding school in St Gallen, later for his studies at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), he was indebted to her, that was the reason for the courtesy visits at Hotel Dolder. He would never have scorned her, although he suffered when he had to visit her. He would never have asked her uncomfortable questions.

The files of the proceeding read: On 15 July 1948 Stefan Beigelbeck and Hildegard Stadler are both acquitted according to paragraph 259/3 StPO. The accused Ludwig Groll is sentenced to eight years hard labour, Josef Muralter to five years and Eduard Nicka to three years. Podezin and Oldenburg, the two presumed main perpetrators, have fled. It is said that they have taken lodgings with Countess Batthyany-Thyssen in Switzerland, in a flat above Lugano. Interpol Vienna informs the Lugano authorities by telegram dated 28.08.1948: “There is the danger, that the two will flee to South America. Please arrest them”. The arrest warrants against the two evaders are published in the “Swiss Police Gazette”, page 1643, art. 16965 on 30.08.1948. But both have already left by then. In his concluding summary the Austrian public prosecutor, Dr Mayer-Maly, who was charged will clearing up the Rechnitz massacre, says: “The true murderers have not yet been found”.

Prefered horses to children

Aunt Margit was not just “rich”. She was infinitely rich. The Thyssen family, who she is said to have slagged off constantly, the ‘rotten seed’, has profited financially from the Second World War, from the coal of their Walsum pit, from steel, from banking. Margit had houses in Switzerland, Rechnitz and in Canada, as well as the apartment ‘Le Mirabeau’ in Monte Carlo – probably for tax reasons – on the terrasse of which I used to watch the sea and the racing track through the binoculars as a child. Like many rich Germans with shady pasts she too owned a hacienda in Uruguay with 2800 hectares of land and in Mozambique she owned the Mafroga estate, where a certain Günther-Hubertus von Reibnitz used to stay, a Baron – and a former member of the Waffen-SS.

Margit lived a life of luxury. She had countless affairs, her husband Ivan knew about it and he received nice sums of money for each of his wife’s bed-stories, in order to keep appearances, that’s what they say.

(Note DL: And Heini Thyssen claimed that Ivy fathered his first child!).

Because for Margit divorce was impossible, she was a devout catholic. Several times a year she undertook big trips, she loved the hunt and hunting parties even more and quite liked the one or other Kir Royal. But it was her horses that made her happier than anything else. Margit was Germany’s most successful horse breeder,

(Note DL: Nonsense. She ran Erlenhof into the ground. Also, the Thyssen family had “bought” it from its original Jewish owner, Moritz James Oppenheimer).

Nebos, her best stallion in her stables was racehorse of the year 1980 and famous for regularly snatching victories on the last furlongs. Margit had a closer relationship with Nebos than she did with her two children, Ivan, named after the father, and Christoph, called Stoffi. When her son Ivan died in a plane crash between Vienna and Lugano, she did not shed a single tear, an anecdote which gets told every year in my family. Margit did not know the concept of motherly love – she never embraced the two.

But she was generous. Aunt Margit gave money not only to my father and grand-parents, but also to other relatives. When she stayed in Vienna, she always ate at the Hotel Sacher, and many people from the family queued up with high hopes. She was also open-handed with her employees. She guaranteed her forester Klaus Gmeiner a life-long position. She donated a piece of woodland to the community of Rechnitz, which was later developed. And her former castle servants received plots of land, which was confirmed to me by Theresia Krausler, a former maid. “We all got something. Houses. Land. The masters gave things to all of us, nobody can complain. I still have one of Countess Margit’s dresses in my case, a velvet suit with little ties”. Aunt Margit turns peasant girls into land owners, for decades they lived without running water, suddenly they had a little piece of garden, a garage, a ballroom dress with little ties – they will never forget this. Every year “The Countess Margit” donated the Christmas tree on the Rechnitz main square, “she was a wonderful soul”, Mrs Krausler says with tears in her eyes, in her sitting room outside the village, a cuckoo clock is ticking on the wall.

(Note DL: You told us she had bought people’s silence, so why don’t you say it now?).

“The dog is crazy”, my father says on the phone. “He is uncontrollable. In the car he jumps to the front and sits on my knee. How is your article about Aunt Margit going?”

(Note DL: Still avoiding mentioning Ivy?).

It seems that information is starting to circle around that I’m writing about her. I received telephone calls from relatives, whom I have never seen. They say: “Why wake up old ghosts?” They believe it would do more harm than good.

“And what do you tell them?”

I answer: Working throught the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung) is only possible, if one recounts again and again what has happened. Of course this sentence is not from me, its a quote from Hanna Arendt. Do you also think that there’s no point in doing the article?

“No. But I doubt that our relatives know anything”.

But that’s the point. Nobody knows anything because nobody ever asked. You all knew about this massacre, and you knew that Aunt Margit was there. But you were too polite to ask. You didn’t want to upset your chances with her.

“Hold on”. I hear the sound of a lighter, a little swishing, I think he must have dropped the handset, then his voice comes back on: “Are you still there?”

Of course I’m still here. It’s the money, isn’t it? It made all of you silent. Aunt Margit paid, and that’s why she had the power. She decided what would be talked about – and what would not be talked about. You are like the people of Rechnitz. Aunt Margit, without wanting to, had all of you in her hands.

Flight to South Africa

Margit was only questioned once by police about the massacre, that’s what the Swiss State Security File, entry C.2.16505 says too. On 07.01.1947 she made the following statement at the criminal section for Vorarlberg in Feldkirch: “Neither my husband nor I ever left the party. The next day, in the morning, I noticed a car that was loaded with clothes. I was told that Jews had been killed during the night, roughly two kilometers from our castle”. During the interrogation, she is also asked about Hans-Joachim Oldenburg, one of the alleged main perpetrators: “Oldenburg was at the castle all night long”, she says, “I can assure you that he had nothing to do with the matter”. She protects him, her lover, because Oldenburg has been seen by witnesses at the massacre. On 11.11.1946 she writes to her sister Gaby in crowded hand-writing: “So as not to be obvious, I have agreed with Oldenburg, that he will first of all go to South America on his own for two years. I am expecting to receive visa for him, what do you say?”. Two years later another letter to Gaby: “Oldenburg has a fantastic offer to go to Argentina and join the biggest dairy farm. He will be there by August”. She helped him flee, the alleged mass murderer, Oldenburg would come back to Germany only in the sixties, when he settled near Düsseldorf.

(Note DL: Tell me, exactly what did this huge family of yours do during the war?).

The other main perpetrator, SS-Hauptscharführer Franz Podezin, ducked down after the war in 1945 in the western occupation zone, and later worked as an agent for them in the GDR. He too came back to the West and moved to Kiel. Everybody who met Podezin, a convicted Nazi through and through during the war, described him as ice-cold and coarse. He lived in Kiel a very inconspicuous life as an insurance broker. He too will be helped to flee later on by Aunt Margit. When the public prosecutor of Dortmund in 1963 finally manages to open proceedings against Podezin for mass murder, he flees to Denmark and then from there, without problems, to Switzerland, to Basel, from where he blackmails Margit and Oldenburg: They must give him money for his flight, otherwise he will “drag” both of them “through the mud”. Sender: Hotel Gotthard-Terminus, Basel, Centralbahnstrasse 13. Podezin was last seen in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he lived quite officially as a tenant of a certain Josef Helmut Hansel, 74 Clifford Avenue, Limbro Park, not far from the Alexandra-Townships. I call.

Of course it’s naive, Podezin, born 1911, has surely been dead for some time – but what if he does pick up? What should I ask him? Where is the mass grave? What does Aunt Margit have to do with it? It rings, for a long time nothing happens, then: “Hello?”, a woman’s voice. “Yes, I did know Mr Podezin, a nice guy, very well read”, says Anette Wilkie in German, the daughter of Mr Hansel, with whom Podezin rented his flat. “ He was sporty and always dressed elegantly, at the end he had problems with his hips, poor man, he was limping”. Podezin, she says, had a camper van and many friends on the coast, he worked for a company called Hytec, hydraulic instruments, valves, pumps, which are used in construction sites in order to evacuate water.

Pits and graves – of course they were Podezin’s speciality.

The company that he worked for, Hytec, still works today with the German company Thyssen-Krupp. Whether Aunt Margit, nee Thyssen, helped him flee in the sixties and then also procured him the job in South Africa? Whether Ivan and Margit visited him there, after all they often went on Safari there, her ‘Africa-Room’ in her villa in Lugano was always crammed full of buffalo horns and ivory. “Mr Podezin left a box behind with private things”, says Anette Wilkie on the phone, “I kept it, in case somebody should call one day. Wait a moment please”. Steps. Silence. More steps. “There are pictures from his time in Africa and a few old clothes with a company logo. Nothing else”. Podezin died in the mid nineties, according to Anette Wilkie three, four friends appeared at Hansel’s house for his funeral, all dead now, all German, who emigrated to South Africa after the war and met up once a week to play cards. Probably Skat.

Jewish propaganda

It is the end of autumn when I travel to Rechnitz for the last time. It is foggy, the houses, fields, the sky, everything grey, the grapes have been collected a long time ago. I join a family meeting.

(Note DL: Where? In Rechnitz? What about the house your family still own in Lugano, where another of your aunts first told you it was all a Jewish conspiracy, or that’s what you told me.).

Aunts, uncles, people whom I hardly know, we sit on long wooden tables, the massacre brings us together. Most of them can still remember Margit and Ivan very well, their travels, their houses, Margit’s horses, Ivan Batthyany’s vanity, and the longer I sit at this table, the more comfortable I feel. The way they all talk, their jokes, the old furniture, the porcelain, the silver sugar bowl – everything familiar.

“What the newspapers write is nonsense”, say the older ones, Elfriede Jelinek’s theater play “The Exterminating Angel”, which deals with Rechnitz and Margit, also presents a wrong picture. Margit, they say, has nothing to do with the massacre, “she was not much liked, that’s true, and was submissive to men”, she is said to have been sex-mad – but a murderer? “Certainly not”. And I nod my head, we all nod our heads, and when one person in the round, an older man, who welcomed me very nicely, although we didn’t know each other, and who looks so nice with his white hair, talks about Jews, about Jewish propaganda, everybody stops listening and they behave as if they can’t understand what he is saying. I too remain silent. I don’t contradict him either, when he says: “Maybe the massacre never happened?”

(Note DL: Funny, you told me on more than one occasion that pretty much all your family were convinced it was a Jewish conspiracy!).

We drink black tea and eat ham sandwiches. Everybody at the table is now talking loudly on top of everybody else, about the grave, about the search, the younger ones ask questions, the older ones evade them. “What’s the point of it all?” – “What for? – “What’s it got to do with us?” Shaking of heads. Silence. “More tea anybody?” Silence. “Enough has been written about the crimes committed on Jews already”, the old man defends himself, “the crimes of the Communists were just as bad”, and again everybody stops listening, nobody responds, “Jelinek is also a Jew, that’s why she writes this crap”. People make jokes, and everybody laughs, and I too laugh, as you laugh and nod in a family, two hours later we say our good-byes.

(Note DL: Jelinek is not Jewish!!).

Once again I get embraced very fondly, these people, this furniture, these cups, everything so familiar, “take good care of our family’s name”, one uncle says to me, who was silent all night long, “you must not disgrace it”. He touches my skin almost tenderly and puts his hand on my cheek, as my father always does it, it’s only later in the car that I feel miserable. There were many reasons why nobody talked to Aunt Margit about the massacre: blocking, laziness, the money.

And indifference.

Because the victims were “only” Jews, many people today still don’t concern themselves with this crime. I call my father and ask him what he thinks of that theory.

“No, I don’t think so”.

So why these remarks at the family meeting about the Jews and about Jelinek?

“He compared the crimes of the Nazis with the crimes of the Communists. It doesn’t make much sense, but it’s legitimate”.

I am reminded of meeting an old man in the restaurant car travelling from Zurich to Vienna, and speaking to him about my article at some length. His attitude was that the Jews would have died anyway, whether in the concentration camp or in this massacre – or of hunger. Before he left the train in Salzburg, he said to me: ‘What does it matter?’ and looked at me in a very puzzled manner.

“Will you be mentioning the family meeting in your article?”, my father asks me, “that will create bad blood”.

I don’t know yet.

(Note DL: You certainly haven’t written here what you told me you had discovered).

He who remains silent makes himself guilty

I am standing in front of Aunt Margit’s grave and am trying to remember her face, but I’m not able to. The wind is taking the last leaves off the tree, it is the middle of November, a few sun beams have fought their way through the overcast Ticino sky – and for a short moment Lake Lugano starts to shimmer. After all the meetings I am sure:

Aunt Margit did not shoot during that moonlit night of 24 March 1945. She did not murder Jews, as the English journalist David Litchfield and all the newspapers allege. There is no proof. There are no witnesses.

(Note DL: And author. I spent fourteen years writing ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’ which you have yet to read. And how about Ivy and what about the witness statements that she liked witnessing the torturing and beating of Jews? So exactly what was it that she paid everyone to keep quiet about? Why did your family hide it and then say it was a Jewish conspiracy? What exactly have they been hiding?).

At midnight, Aunt Margit did not stand in the cold in front of that pit, where the naked men and women kneeled down in rows. She was laughing and dancing at the castle, when the emaciated bodies fell down and into the ground, she laughed and danced with the murderers, when they returned to the castle at three o’clock in the morning, while outside the murdered Jews were heaped on top of each other in a pit like sardines, somewhere in Rechnitz.

And while the 180 bodies were rotting, Aunt Margit travelled on a cruise ship through the summer-blue Aegean every year, drank Kir Royal in Monte Carlo and hunted deer in the autumnal woodlands of the Burgenland.

Aunt Margit enjoyed the rest of her long life, although she knew everything about the massacre. Rotten seed.’

(Note DL: And Ivy? And your father, who profited from her smelly money? Not once in this whole damage limitation and guilt containment exercise do you say what an appalling atrocity the Rechnitz massacre was! Even Georg Thyssen admitted this to the Jewish Chronicle, while your aunt Christine Batthyany in Hamburg and Professor Wolfgang Benz in Berlin were denying it ever happened).

End of Translation (copyright Caroline Schmitz)

|

Margit Batthyany-Thyssen |