Posts Tagged ‘banking’

Monday, March 5th, 2018

| Dieses Buch zu rezensieren ist für uns ein echtes Ärgernis, da so viele Stränge und Einzelheiten darin unserem bahn-brechenden Werk über die Thyssens entlehnt sind, welches ein Jahrzehnt zuvor erschien, Derix uns nichtsdestotrotz keine einzige Nennung gewährt. Es ist erstaunlich, dass sie nicht genug berufsethisches Gefühl aufbringt, unseren Beitrag zur Thyssenschen Geschichtsschreibung an zu erkennen; vor allem wo sie doch auf einer Konferenz 2009 ausdrücklich erklärt haben soll, dass nicht-akademische Betrachtungsweisen, denen gegenüber die Fachwelt häufig Unbehagen empfände (und Berührungsängste mit der Angst vor Statusverlust im Kampf um Deutungshoheit), einen immer größeren Raum einnehmen.

Frau Derix selbst ist natürlich nicht vom ängstlichen Typ, auch wenn sie ziemlich scheinheilig wirkt. Sie scheint vorauseilenden Gehorsam an den Tag zu legen und voller Hingabe, die Erwartungen ihrer vermutlich parteiischen Zahlmeister in Gestalt der Fritz Thyssen Stiftung erfüllen zu wollen. Leider ist sie offensichtlich auch nicht die vorausschauendste Person, da sie z.B. schreibt, Heinrich Lübke, Direktor der August Thyssen Bank (er starb 1962) sei später Bundespräsident Deutschlands gewesen (jener Heinrich Lübke war in dieser Position bis 1969).

Aber die intellektuellen Unzulänglichkeiten der Simone Derix sind weitaus gravierender als es simple Sachfehler wären, die ohnehin mindestens einem ihrer zwei langjährigen Mitarbeiter, drei Projektleiter, vier akademischen Mentoren und sechs wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiter hätten auffallen müssen. Sie versucht uns allen Ernstes zu erzählen, dass die Erforschung der Lebenswelten von reichen Personen ein vollkommen neuer Zweig der akademischen Forschung sei, und dessen illustrer Pionier sie selbst. Weiss sie denn nicht, dass Geschichtsschreibung klassischerweise ausschließlich von Reichen, über Reiche und für Reiche getätigt wurde? Hat sie bereits vergessen, dass selbst einfachstes Lesen und Schreiben bis vor hundert fünfzig Jahren Privilegien der wenigen Mitglieder der oberen Schichten waren?

Gleichzeitig erscheint sie, im Gegensatz zu uns, keine persönlichen Erfahrungen mit außergewöhnlich reichen Menschen erworben zu haben. Ihre Förderung, während eines früheren Vorhabens, durch die finanzstarke Gerda Henkel Stiftung war vermutlich gleichermaßen auf Armeslänge. Reiche Leute verkehren nur mit reichen Leuten, und es gibt keinerlei Anzeichen dafür, dass Derix sich irgendwie für ernst zu nehmende Kommentare über deren Lebensstil qualifiziert hätte, es sei denn, sie wurde für ihr vorliegendes Werk pro Wort bezahlt…

Was allerdings tatsächlich neu ist, ist dass der weg gefegte Feudalismus durch etablierte demokratische Gesellschaften ersetzt wurde, in denen Wissen allgemein zugänglich ist und die Gleichheit vor dem Gesetz Priorität hat. Ja, Derix hat Recht, wenn sie sagt, dass es schwierig ist, die Archive von Ultra-Reichen einzusehen. Diese wollen immer nur glorreiche Dinge über sich verbreiten und die Realitäten hinter ihrem überwältigenden Reichtum verbergen. Aber es ist grotesk so zu tun, als hätten die Thyssens jetzt auf einmal beschlossen, sich in Ehrlichkeit zu üben und offiziellen Historikern großzügig zu erlauben, ihre privatesten Dokumente zu sichten. Der einzige Grund, weshalb Simone Derix nunmehr einige kontroverse Fakten über die Thyssens publiziert, ist, dass wir diese bereits publiziert haben. Der Unterschied liegt darin, dass sie unsere Belege mit ausgesprochen positiven Termini neu umspannt, um dem allgemeinen Programm der Schadensbegrenzung dieser Serie gerecht zu werden.

Derix scheint zu glauben, auf diese Weise auf zwei Hochzeiten tanzen zu können; ein Balanceakt der dadurch drastisch erleichtert wird, dass sie bereits zu Anfang ihrer Studie jegliche Erwägungen bezüglich Ethik und Moral kategorisch ausschließt. Die Tatsache, dass die Thyssens ihre deutschen Firmen (inklusive derer, die Waffen produzierten und Zwangsarbeiter verwendeten) hinter internationalen Strohmännern tarnten (mit dem zusätzlichen Bonus der groß angelegten Umgehung deutscher Steuern) wird von Derix als irreführende Beschreibung dargestellt, welche “eine staatliche Perspektive impliziert” und angewandt wird, um “eine gewünschte Ordnung zu etablieren, nicht eine bereits gegebene Ordnung abzubilden”. Als ob “der Staat” eine Art hinterhältige Einheit sei, die bekämpft werden müsse, und nicht das gemeinschaftliche Unterstützungswesen für alle gleichgestellten, rechtstreuen Bürger, so wie wir Demokraten ihn verstehen.

Dies ist nur eine von vielen Äußerungen, die zu zeigen scheinen, wie sehr die möglicherweise als autoritär zu beschreibende Einstellung ihrer Sponsoren auf Derix abgefärbt hat. Die Tatsache, dass Akademiker, die bei öffentlich geförderten Universitäten angestellt sind, in solch einer Weise von den eigennützigen Institutionen Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, Stiftung zur Industriegeschichte Thyssen und ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archiv als Public Relations Vermittler missbraucht werden, ist äusserst fragwürdig; v.a. wenn man angeblich akademische Maßstäbe anlegt. Und vor allem wenn von diesen behauptet wird, sie seien unabhängig.

****************

In der Welt von Simone Derix werden die Thyssens immer noch (!) v.a. als „Opfer“, „(Steuer-)flüchtlinge“, als „enteignet“ und „entrechnet“ beschrieben; selbst wenn sie ein oder zwei Mal über 500 Seiten hinweg kurz zugeben muss, dass es ihnen in der “langfristigen Perspektive (…) gelungen zu sein (scheint), Vermögen stets zu sichern und für sich verfügbar halten zu können”.

Was ihre Beziehung zum Nationalsozialismus angeht, so nennt sie sie damit „verwoben“, „verquickt“, sagt, dass sie in ihm „präsent“ waren, in ihm „lebten“. Mit zwei oder drei Ausnahmen werden die Thyssens nie richtiger Weise als handelnde, profitierende, u.v.a. zum Bestand des Regimes beitragende Akteure beschrieben. Stattdessen wird die Schuld wiederum, genau wie in Band 2 („Zwangsarbeit bei Thyssen“), weitgehendst den Managern zugeschrieben. Dies ist für die Thyssens sehr praktisch, da die Familien dieser Männer nicht die Mittel haben, gleichwertige Gegendarstellungen zu publizieren, um ihre Lieben zu rehabilitieren.

Wenn Simone Derix jedoch davon spricht, dass „aus einer nationalstaatlichen Perspektive (…) diese Männer als Ganoven erscheinen (mussten)“, dann überschreitet sie bei Weitem die Grenzen der fairen Kommentierung. Die Ungeheuerlichkeit ihrer Behauptung verschlimmert sich dadurch, dass sie es unterlässt, Beweise beizufügen, so wie in unserem Buch geschehen, die zeigen, dass alliierte Ermittler klar aussprachen, dass sie die Thyssens selbst, nicht ihre Mitarbeiter, für die wahren Täter und Verdunkler hielten.

Und dennoch gibt Derix in ihrem Streben nach Thyssen Glanz vor, deutsche Größe, Ehre und Vaterlandsliebe zu beschwören. Immer wieder und auf bombastische Weise behauptet sie z.B., dass die Grablege / Gruft in Schloss Landsberg bei Mülheim-Kettwig „zukünftig die Präsenz der Familie und ihre Verbundenheit mit dem Ruhrgebiet garantieren (würde)“, und dass es im Falle der Thyssens einen „(unauflösbaren) (…) Zusammenhang von Familie, Unternehmen, Region und Konfession“ gibt. Dabei stuft sie die Thyssens nicht, wie es richtig wäre, im Rahmen der Industriellen-Familien Krupp, Quandt, Siemens und Bosch ein, sondern zieht es vor, ihren Namen übertreibend mit denen der Herrscherhäuser Bismarck, Hohenzollern, Thurn und Taxis und Wittelsbach zu umgeben.

In Wirklichkeit wählten viele der Thyssen-Erben eine Abkehr von Deutschland und ein transnationales Leben im Ausland. Ihr Mausoleum ist noch nicht einmal öffentlich frei zugänglich. Im Gegensatz zu dem was Derix andeutet, ist der starke, symbolische Name, der so eine Anhänglichkeit in Deutschland hervorruft, einzig der der Aktiengesellschaft Thyssen (jetzt ThyssenKrupp AG), als einem der Hauptarbeitgeber im Land. Dies hat überhaupt nichts mit Respekt für die Abkömmlinge des herausragenden August Thyssen zu tun, die aufgrund ihrer gewählten Abwesenheit in ihrer Mehrzahl in Deutschland absolut unbekannt sind.

****************

In diesem Zusammenhang ist es bezeichnend, dass Simone Derix die Thyssens als „altreich“ sowie „arbeitende Reiche“ kategorisiert. Obwohl Friedrich Thyssen Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts bereits ein Bankier war, so waren es doch erst seine Söhne August (75% Anteil) und Josef (25% Anteil), die ab 1871 (und mit den Profiten aus zwei Weltkriegen) durch ihre unermüdliche Arbeit, und die ihrer Arbeiter und Angestellten, das enorme Thyssen-Vermögen schufen. Ihresgleichen ward in den nachfolgenden Thyssen-Generationen nie wieder gesehen.

So wurden die Thyssens ultravermögend und spalteten sich komplett von der etablierten adelig-bürgerlischen Oberschicht ab. Sie können wirklich nicht als „altreich“ bezeichnet werden, und ihre Erben auch nicht, auch wenn diese alles in ihrer Macht taten, um sich die äußere Aufmachung der Aristokratie anzueignen. (Hier stellt sich die dringende Frage, wieso Band 6 der Serie ausgerechnet „Fritz und Heinrich Thyssen – Zwei Bürgerleben in der Öffentlichkeit betitelt wurde). Dies beinhaltete die Einheiratung in den ungarischen, zunehmend falschen Adel, wonach, so muss es sogar Derix zugeben, mit dem Anbruch der 1920er Jahre jeder fünfte Ungar behauptete, der Aristokratie des Landes anzugehören.

Die Linie der Bornemiszas, in die Heinrich einheiratete z.B. waren eben nicht das alte „Herrschergeschlecht“ der Bornemiszas, auch wenn Derix das immer noch so wiederholt. Die Thyssen-Bornemiszas hatten Verbindung zum niederländischen Königshaus, nicht weil Heinrich’s Frau Margit bei Hofe selbsternannt „besondere Beachtung“ fand, sondern weil Heinrich in jenem Land wichtige Geschäftsinteressen vertrat. Dadurch wurde Heinrich Thyssen zum Bankier für das niederländische Königshaus und ein persönlicher Bekannter seines Namensvettern Heinrich, des Prinzgemahls der Königin Wilhelmina.

Außer für solche wirtschaftlichen Beziehungen wollten weder der deutsche, noch der englische oder irgend ein anderer europäischer Adel in Wirklichkeit diese Aufsteiger in ihren engeren Reihen willkommen heissen (Religion spielte natürlich auch eine Rolle, denn die Thyssens waren und sind katholisch). Das heisst, bevor nicht gesellschaftliche Konventionen mit Beginn der 1930er Jahre sich weit genug geändert hatten und ihre Töchter in die tatsächlich alten ungarischen Dynastien der Batthyanys und Zichys einheiraten konnten.

Aber bis dahin ließen sich die Brüder, basierend auf ihrem hervorragenden Reichtum, nicht davon abhalten, sich viele der erhabenen Sphären selbst zu erschließen. Laut Derix verbrachte Fritz Thyssen Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts sogar Zeit damit, Pferde aus England zu importieren, die englische Fuchsjagd in Deutschland einzuführen und sich eine Hundemeute zur Hetzjagd auf Hirsche zuzulegen. Weiterhin ließ er anscheinend den Trakt für Dienstpersonal seines neu gebauten Hauses in Mülheim niedriger halten, um die „Differenz und Distanz zwischen Herrschaft und Personal“ zu signalisieren.

Dies sind tatsächlich erstaunliche, neue Offenbarungen, die zeigen, dass das traditionelle Bild, welches die Thyssen Organisation bisher herausgab, nämlich das des „Bad Cop“ Fritz Thyssen (deutscher Industrieller, „temporärer“ Faschist), „Good Cop“ Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza (Ungar, „Adeliger“) sogar noch irreführender ist, als wir bisher angenommen hatten.

****************

Wirklich bedauernswert sind die Versuche von Derix, Fritz Thyssen als gläubigen Peacenik und Mitglied einer gemäßigten Partei darzustellen. Und genauso sind es ihre lang anhaltenden Verrenkungen, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza als perfekt assimilierten, ungarischen Gutsherren zu portraitieren. Sie berichtet allerdings, dass Heinrich’s Frau erwähnt hatte, dass er kein Wort der Sprache beherrschte; was allerdings Felix de Taillez in Band 6 nicht davon abhält, zu behaupten, er habe Ungarisch gesprochen. „Wenn Sie sie nicht schlagen können, dann müssen Sie sie verwirren“ war eines von Heini Thyssen’s Mottos. Es ist offensichtlich auch das Motto dieser Thyssen-finanzierten Akademiker geworden.

Währenddessen ist das Buch von Derix das erste von der Thyssen Organisation unterstützte Werk, das bestätigt, dass Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza eben doch seine deutsche (damals preussische) Staatsangehörigkeit beibehielt. Derix traut sich sogar soweit hervor, zu sagen, dass die ungarische Staatsangehörigkeit „von Heinrich möglicherweise aus funktionalen Gründen gewählt“ worden war. Doch diese Perlen der Aufrichtigkeit werden unter den Springbrunnen ihrer überschwänglichen Propaganda rasch erstickt, die darauf abzielt, die Thyssens der zweiten Generation besser dastehen zu lassen, als sie waren. Dies erstreckt sich auch darauf, die Rolle des August Thyssen Junior von der des schwarzen Schafs der Familie auf die des engagierten Unternehmers um zu schreiben.

Andererseits unterlässt es die Autorin immer noch, irgendwelche unternehmerischen Details zum Leben des weitaus wichtigeren Heinrich Thyssen in England um die Jahrhundertwende zu liefern (Stichworte: Banking und Diplomatie). Wie genau machte die Familie die enge Bekanntschaft von Menschen wie Henry Mowbray Howard (britischer Verbindungsoffizier beim französischen Marineministerium) oder Guy L’Estrange Ewen (Sonderbotschafter der Britischen Monarchen)? Eine große Chance zur echten Transparenz wurde hier vergeudet.

Derix unterlässt es weiterhin, das Augenmerk darauf zu richten, dass die Familienzweige August Thyssen und Josef Thyssen sich in sehr unterschiedliche Richtungen entwickelten. August’s Erben nützten Deutschland aus, verließen und verrieten es und waren ausgesprochen „neureich“, außer Heinrich’s Sohn Heini Thyssen-Bornemisza und dessen Sohn Georg Thyssen, die sich tatsächlich mit dem Management ihrer Firmen befassten.

Im Unterschied dazu verblieben Josef Thyssen’s Erben Hans Thyssen und Julius Thyssen in Deutschland (bzw. waren bereit dorthin aus der Schweiz zurück zu kehren, als in den 1930er Jahren Devisenbeschränkungen erlassen wurden), zahlten ihre Steuern, arbeiteten im Thyssen Konzern, bevor sie in den 1940er Jahren ihre Anteile verkauften, ihre Resourcen bündelten und berufliche Karrieren einschlugen. Nur Erben Josef Thyssen’s sind auf der Liste der 1001 reichsten Deutschen des Manager Magazins aufgeführt, aber aus unerklärten Gründen lässt Derix diese tatsächlich „arbeitenden reichen“ Thyssens in ihrer Studie weitgehenst unerwähnt.

****************

Glücklicherweise konzentriert Simone Derix nicht all ihre Kräfte auf schöpferische Erzählungen und Plagiarisierung, sondern bietet auch wenigstens einige politökonomische Fakten an. So legt sie offen, dass Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza bis 1933 ein Mitglied des Aufsichtsrats der Vereinigten Stahlwerke in Düsseldorf war, also bis nach Adolf Hitler’s Machtergreifung. Dies, in Kombination mit ihrer Aussage, dass sich Heinrich „bereits 1927/8 (von Scheveningen in den Niederlanden) dauerhaft nach Berlin orientiert zu haben (scheint)“ widerlegt eine der größten Thyssenschen Dienlichkeitslegenden, nämlich die, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza habe ab 1932 seinen Hauptwohnsitz in der neutralen Schweiz gehabt (i.e. praktischerweise vor Hitler’s Machtergreifung); nachdem er „Deutschland noch rechtzeitig verlassen hatte“; obschon dies Derix nicht davon abhält, auch diese Täuschung danach gleichfalls noch zu wiederholen (- „Wenn Sie sie nicht schlagen können, dann müssen Sie sie verwirren“ -).

Tatsache ist, dass Heinrich Thyssen, obwohl er 1932 die Villa Favorita in Lugano (Schweiz) kaufte, weiterhin den Großteil seiner Zeit in verschiedenen Hotels verbrachte, v.a. aber in einer permanenten Hotelsuite in Berlin und ausserdem einen Wohnsitz in Holland beibehielt (wo Heini Thyssen fast allein, bis auf das Personal, aufwuchs). („Sein Tessiner Anwalt Roberto van Aken musste ihn 1936 daran erinnern, dass er immer noch nicht seine permanente Aufenthaltsbewilligung in der Schweiz beantragt hatte. Erst im November 1937 wurden Heinrich Thyssen und seine Frau mit je einem Ausländerausweis der Schweiz ausgestattet“ – Die Thyssen-Dynastie, Seite 149).

Derix justiert auch den alten Thyssen Mythos neu, wonach Fritz Thyssen und Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza geschäftlich kurz nach ihrer Erbschaft von ihrem Vater, der 1926 starb, geschäftlich getrennte Wege gegangen seien. Wir haben stets gesagt, dass die beiden Brüder bis tief in die zweite Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts eng miteinander verbunden blieben. Und simsalabim plötzlich gibt Derix nunmehr an: „Bisher wird davon ausgegangen, dass die Separierung des Vermögens von Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza und Fritz Thyssen 1936 abgeschlossen war“. Sie fügt hinzu: „Trotz aller Versuche, die Anteile von Fritz Thyssen und Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza voneinander zu separieren, blieben die Vermögen von Fritz und Heinrich (vertraglich geregelt) bis in die Zeit nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg miteinander verschränkt“.

Aber es ist ihr folgender Satz, der am ärgerlichsten ist: „Außenstehende konnten diesen Zusammenhang offenbar nur schwer erkennen“. In Wahrheit war die Situation deshalb so undurchsichtig, weil die Thyssens und ihre Organisation erhebliche Anstrengungen unternahmen und alles ihnen Mögliche taten, um die Dinge zu verschleiern, v.a. da dies bedeutete, dass sie die gemeinsame Unterstützung des Naziregimes durch die Thyssen Brüder tarnen konnten.

****************

Unter der großen Anzahl der Berater der Thyssens stellt die Autorin insbesondere den Holländer Hendrik J Kouwenhoven vor, und zwar als die Hauptverbindung zwischen den beiden Brüdern Fritz und Heinrich. „Er tat Chancen auf und erdachte Konstruktionen“, so schreibt sie. Kouwenhoven arbeitete seit 1914 bei der Handels en Transport Maatschappij Vulcaan der Thyssens und danach bei ihrer Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart (BVHS) in Rotterdam seit ihrer offiziellen Gründung 1918 bis zu seiner Entlassung durch Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza im zweiten Weltkrieg.

Vermögensverwaltungsgesellschaft und Trust Department der BVHS war das Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor (RTK), welches Derix als „Lagerstätte für das Finanzkapital der (Thyssen) Unternehmen wie für die privaten Gelder (der Thyssens)“ beschreibt. Sie sagt nicht, in welchem Jahr diese Gesellschaft gegründet wurde. Laut Derix wurden „das Gebäude der Vermögensverwaltung, der Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza alle wichtigen Papiere anvertraut hatte (…), am 14. Mai 1940 bei einem Luftangriff auf Rotterdam (…) vollständig zerstört“. Für uns klingt das wie eine höchst fragwürdige Information.

Über die Akten der BVHS sagt Derix knapp: „Von der BVHS ist kein geschlossener Quellenbestand erhalten“. Wie praktisch, insbesondere da niemand außerhalb der Thyssen Organisation jemals in der Lage sein wird, diese Aussage wahrhaft unabhängig zu überprüfen; zumindest nicht bevor der Schutzmantel des Professor Manfred Rasch, Leiter des ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archivs, sich in den Ruhestand verabschiedet.

Derix spielt auf die „frühe Internationalisierung des (Thyssen) Konzerns“ ab 1900 an, und rechnet ihre Kenntnisse über Rohstoffankäufe und den „Aufbau eines eigenen Handels- und Transportnetzes“ Jörg Lesczenski zu, der zwei Jahre nach uns publizierte, und dessen Buch ebenfalls, so wie das von Derix, durch die Fritz Thyssen Stiftung unterstützt wurde. Aber sie unterlässt Querverweise auf die ersten Steueroasen (inklusive der der Niederlande), die sich zum Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts hin entwickelten und überlässt diesen Bereich bequem zukünftiger Forschung, die „weitaus intensiver“ ausfallen müsse „als dies bislang vorliegt“.

Derix nennt die Transportkontor Vulkan GmbH Duisburg-Hamborn von 1906 mit ihrer Filiale in Rotterdam (siehe oben) und die Deutsch-Überseeische Handelsgesellschaft der Thyssenschen Werke mbH in Buenos Aires von 1913 (übrigens: bis zum heutigen Tage ist die ThyssenKrupp AG im großen Stil im Rohmaterialhandel aktiv). Sie schreibt auch, dass die US-Amerikanischen Kredite für den Thyssen Konzern 1919 via der Vulcaan Coal Company begannen (verschweigt jedoch, dass diese Firma in London angesiedelt war).

****************

Nach Angaben von Simone Derix begann August Thyssen 1919 damit, seine Anteile an den Thyssen Unternehmen an seine Söhne Fritz und Heinrich zu übertragen, zunächst die von Thyssen & Co. und ab 1921 die der August Thyssen Hütte. Sie fügt hinzu, dass „bestehende Thyssen Einrichtungen im Ausland für Tausch und Umschichtung von Beteiligungen“ genutzt wurden.

Ab 1920 kaufte Fritz Thyssen in Argentinien Land. Die Thyssensche Union Banking Corporation (UBC), 1924 im Harriman Building am Broadway, New York, gegründet, wird währenddessen allein in der Sprache der „transnationalen Dimension des Thyssenschen Finanzgeflechts“ beschrieben und als „die American branch“ der Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart.

Wir hatten bereits in unserem Buch beschrieben, wie Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, über Hendrik Kouwenhoven, in der Schweiz 1926 die Kaszony Stiftung institutierte, um seine ererbten Firmenanteile zu deponieren; und 1931 die Stiftung Sammlung Schloss Rohoncz, als Depot für seine Kunstgegenstände, die er ab 1928 als leicht bewegliche Kapitalanlagen kaufte. Jetzt schreibt Derix, dass letztere ebenfalls bereits 1926 gegründet worden sei. Dies ist estaunlich, da es bedeutet, dass dieses Finanzinstrument ganze zwei Jahre bevor Heinrich Thyssen das erste Gemälde kaufte, gegründet wurde, das seinen Weg in die Sammlung fand, die er „Sammlung Schloss Rohoncz“ nannte (obwohl keines der Bilder jemals auch nur in die Nähe seines ungarischen, dann österreichischen Schlosses fand, in dem er ab 1919 nicht mehr lebte).

Die Terminierung der Bildung dieses Offshore-Instruments zeigt einmal mehr wie gekünstelt Heinrich Thyssen’s Neuerfindung als „Kunstkenner und Sammler“ tatsächlich war.

Derix gibt sogar freimütig zu, dass die Thyssenschen Familienstiftungen als „Gegenspieler (…) von Staat und Regierung auftraten“. Jedoch versäumt sie es, genauso wie Johannes Gramlich in Band 3 („Die Thyssens als Kunstsammler“) die Logistik des Transfers von ca. 500 Bildern durch Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza in die Schweiz in den 1930er Jahren zu beschreiben, inklusive der Tatsache, dass dies eine Methode der großangelegten Kapitalflucht aus Deutschland heraus darstellte. Die assoziierten Themen der Steuerflucht und Steuerumgehung bleiben vollständig außerhalb ihres akademischen Radars, und sie lässt damit z.B. unsere dokumentierten Belege aus.

****************

In einer weiteren, wagemutigen Um-Schreibung der offiziellen Thyssen Historie erklärt die Autorin, dass die Thyssen Brüder in ihren Finanzangelegenheiten oft parallel agierten. Und so kam es, dass die Pelzer Stiftung und Faminta AG von Kouwenhoven für Fritz Thyssen’s Seite in der Schweiz gegründet wurden. (Derix bleibt vage bestreffs genauer Daten. Wir haben veröffentlicht: 1929 für Faminta AG und die späten 1930er Jahre für die Pelzer Stiftung).

Derix weist darauf hin, dass diese beiden Finanzinstrumente auch geheime Transaktionen zwischen den zwei Thyssen Brüdern erlaubten. Vage bleibend fügt sie hinzu, sie hätten auch „das Auslandsvermögen der August Thyssen Hütte vor einer möglichen Beschlagnahmung durch deutsche Behörden (gesichert)“. Dabei verschweigt sie jegliche Referenz betreffs Zeitskala, und demnach wann genau solch eine Beschlagnahmung im Raum getanden haben soll (gibt sie hier etwa zu verstehen, dass diese bereits vor Fritz Thyssen’s Flucht aus Deutschland im September 1939, also im Zeiraum 1929-1939 zu erwarten gewesen sein könnte?).

Gleichzeitig etablierten Fritz und Amelie Thyssen einen festen Standort in den 1920er Jahren im Süden des deutschen Reiches, und zwar in Bayern (weit weg vom Thyssenschen Kerngebiet der Ruhr), welchen Derix als „bisher von der Forschung wenig beachtet“ darstellt. Natürlich war dieser monarchistischste aller deutschen Staaten nicht nur nah an der Schweiz, sondern er war zu jener Zeit auch die Wiege der Nazi Bewegung. Auch Adolf Hitler zog München Berlin vor.

Alle Finanzinstrumente der Familie wurden währenddessen weiter durch die Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor in den Niederlanden verwaltet. Diese „neu geschaffenen Banken, Gesellschaften, Holdings und Stiftungen wurden über Beteiligungen mit den produzierenden Thyssenschen Unternehmen verknüpft“, so Derix weiter.

Diese Unternehmen usw. waren aber ebenso mit der aufsteigenden Nazi Bewegung verknüpft, so z.B. durch einen Kredit von ca. 350,000 Reichsmark, den ihre Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart ca. 1930 der NSDAP gewährte, zu einer Zeit, als sowohl Fritz Thyssen als auch Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza beherrschende Anteile an der BVHS hatten.

Laut Derix war es im Jahr 1930, dass Heinrich Thyssen anfing, seine Anteile an den Vereinigten Stahlwerken an Fritz zu verkaufen, während Fritz seine holländischen Anteile an Heinrich verkaufte. In der Nachfolge war Heinrich Thyssen dann allein in Kontrolle der Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart, und zwar von 1936 an.

Insbesondere war es eine Thyssen Firma mit Namen Holland-American Investment Corporation (HAIC), die Fritz Thyssen’s Kapitalflucht aus Deutschland ermöglichte. Laut Derix erwarb die Pelzer Stiftung „im Herbst 1933 von Fritz Aktien der HAIC und damit seine darin zusammengefassten niederländischen Beteiligungen. Dieses Geschäft geschah mit Zustimmung der deutschen Behörden, die von der HAIC wussten. Aber 1940 sahen die Deutschen, dass eine erhebliche Diskrepanz bestand zwischen 1,5 Millionen Reichsmark der niederländischen Beteiligungen in HAIC wie angegeben, und dem tatsächlichen Wert von 100 bis 130 Millionen RM.“

Dies ist überwältigend, da der heutige Wert dieser Summe bei vielen hundert Millionen Euros liegt!

Wenn man bedenkt, dass Heinrich’s Frau angab, dass er ca. 200 Millionen Schweizer Franken seines Vermögens in neutrale Länder gebracht hatte, dann würde dies bedeuten, dass die Thyssen Brüder es möglicherweise geschafft hatten, zusammen einen Gegenwert in Bar aus Deutschland abzuziehen, der fast dem gesamten Geldwert der Thyssen Unternehmen entsprach! Dies aber ist keine Schlussfolgerung, die Simone Derix zieht.

Man beginnt, sich zu wundern, was eigentlich zur Beschlagnahmung übrig gewesen sein soll, nachdem Fritz Thyssen bei Kriegsbeginn 1939 Deutschland verließ. Derix räumt ein, dass seine Flucht nicht zuletzt deshalb stattfand, weil er seine eigennützigen Finanztransaktionen lieber von der sicheren Schweiz aus, mit Hilfe des Heinrich Blass bei der Schweizerischen Kreditanstalt in Zurich, vervollständigen wollte.

Obwohl wir einige Hinweise auf Summen herausarbeiten konnten, so hatten wir doch keine Ahnung, dass das Gesamtausmaß der Kapitalflucht durch die Gebrüder Thyssen so dramatisch war. Dass Simone Derix diesen Punkt im Namen der Thyssen Organisation anspricht ist beachtenswert; selbst wenn sie es unterlässt, die angemessenen Schlussfolgerungen zu ziehen – möglicherweise da diese ihrem „Blue-Sky“ Auftrag zuwiderlaufen würden.

Fürwahr und in den Worten des weitaus erfahreneren Harald Wixforth steht für diese „Großkapitalist(en) (…) tatsächlich (…) das Profitinteresse des Unternehmens immer über dem Volkswohl“.

Es versteht sich von selbst, dass wir die Bände von Harald Wixforth und Boris Gehlen über die Thyssen Bornemisza Gruppe 1919-1932 und 1932-1947 mit Interesse erwarten.

****************

In diesem korrigierten offiziellen Licht überrascht Derix’s Zugeständnis, dass Fritz und Amelie Thyssen’s „Enteignung (…) jedoch nicht unmittelbar mit einer Einschränkung der Lebensführung verbunden (war)“ nun wirklich überhaupt nicht mehr.

Die Autorin gibt auch zum ersten Mal offizielle Abreisedaten für Fritz Thyssen’s Tochter Anita, ihren Ehemann Gabor und ihren Sohn Federico Zichy nach Argentinien bekannt. So fuhren sie anscheinend am 17.02.1940 an Bord des Schiffs Conte Grande von Genua in Richtung Buenos Aires. Um sie mit der standesgemäßen finanziellen Rückendeckung auszustatten waren kurz zuvor Anteile der Faminta AG in den Übersee-Trust Vaduz transferiert worden, dessen einzige Begünstigte Anita Zichy-Thyssen war, die die ungarische Staatsbürgerschaft besaß.

Derix schreibt sodann, dass Fritz Thyssen im April 1940 „sein politisches Wissen über das Deutsche Reich und die deutsche Rüstungsindustrie als ein Gut (einbrachte), das er im Tausch gegen die Unterstützung seiner Anliegen anbieten konnte“. Was aber genau waren diese Anliegen? Der hochmütig wahnhafte Fritz glaubte offensichtlich, dass er Hitler genauso einfach loswerden könne, wie er ihm einstmals zur Macht verholfen hatte. Dafür war er bereit, deutsche Staatsgeheimnisse mit dem französischen Außenminister Alexis Leger und dem Rüstungsminister Raoul Dautry in Paris zu teilen. Aber für Derix ist dieses Verhalten keinesfalls etwas Strittiges wie z.B. aktiver Landesverrat oder ein Ausdruck der Macht, sondern nichts weiter als das legitime Recht eines Ultra-Reichen, die Wahlmöglichkeiten seines gehobenen Lebensstils auszudrücken.

Während alle vorangegangene Thyssen Biografen, mit Ausnahme von uns, behauptet haben, die Thyssens hätten unausprechliche „Qualen“ während ihrer Inkarzeration in Konzentrationslagern erlebt, bestätigt Derix nunmehr unsere Information, dass sie die meiste Zeit ihrer Inhaftierung in Deutschland im bequemen, privaten Sanatorium des Dr Sinn in Berlin-Neubabelsberg verbrachten. Derix schreibt, sie seien dort „auf Befehl des Führers“ und „auf Ehrenwort“ gewesen. Dabei gab Fritz und Heinrich’s persönlicher Freund Hermann Göring während seiner alliierten Befragungen nach dem Krieg an, er habe diese privilegierte Behandlung initiiert. Nach Neubabelsberg wurden sie in verschiedene Konzentrationslager gebracht, aber Derix ist nunmehr gezwungen einzugestehen, dass sie sich jeweils eines Sonderstatuses erfreuten, der „an allen Aufenthaltsorten belegbar“ sei. Was die Frage aufwirft, warum deutsche Historiker es in der Vergangenheit für nötig erachtet haben, diese Fakten falsch darzustellen.

Derix’s Liste der alliierten Befragungen des Fritz Thyssen nach dem Krieg ist besonders bemerkenswert. Sie illustriert, mit welchem Ernst er der, wenn auch Unternehmens-bedingten, Kriegsverbrechen beschuldigt wurde; genug um ihn mit Inhaftierung zu bestrafen:

Im Juli 1945 wurde er ins Schloss Kransberg nahe Bad Nauheim gebracht, und zwar zum sogenannten Dustbin Zentrum für Wissenschaftler und Industrielle der amerikanischen und britischen Besatzungsmächte. Im August kam er nach Kornwestheim, und im September zum 7th Army Interrogation Center in Augsburg.

Derix erwähnt auch vage, Fritz Thyssen sei irgendwann 1945 durch Robert Kempner, Chefankläger bei den Nürnberger Prozessen, befragt worden.

Thyssen erlitt einen Kollaps und musste sich in ärztliche Behandlung begeben. Er wurde ins US Gefangenenlager Seckenheim gebracht, danach nach Oberursel. Sein Gesundheitszustand verschlimmerte sich. Von April bis November 1946 war er in verschiedenen Krankenhäuser und Kuranstalten zwischen Königstein (wo er eine unerwartete Besserung erlebte) und Oberursel. Ab November 1946 war Fritz Thyssen als Zeuge bei den Nürnberger Nachfolgeprozessen (man nimmt an, in den Fällen von Alfried Krupp und Friedrich Flick) geladen, während er weiterhin ständig Krankenhausbehandlungen erhielt, diesmal in Fürth.

Am 15.01.1947 wurde Fritz Thyssen entlassen und vereinigte sich wieder mit seiner Frau Amelie in Bad Wiessee. Danach kam sein deutscher Entnazifizierungsprozess in Königstein, wo er und Amelie im Sanatorium des Dr Amelung wohnten. In diesem Gericht, wie es seinem unaufrichtigen Charakter entsprach, gab Fritz Thyssen an, keinen Heller zu besitzen.

Währenddessen, so Derix, trat Anita Zichy-Thyssen mit Edmund Stinnes in Kontakt, der in den USA lebte, und mit dessen Schwager Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, einem engen Mitarbeiter des US Geheimdienstchefs Allen Dulles. Im Frühjahr 1947 traf sie sich, um „eine Ausreisegenehmigung ihrer Eltern nach Amerika zu erwirken“, mit dem früheren US-Senator Burton K Wheeler in Argentinien, der 1948 nach Deutschland reiste „um Fritz Thyssen aus seinen Denazifizierungsschwierigkeiten zu helfen“. Dies ist sicherlich ein Aspekt einer Einflussnahme auf höchster Ebene, die wir mit weitaus größeren Einzelheiten in unserem Buch präsentiert haben, die aber Johannes Bähr in seinem Band 5 der Serie („Thyssen in der Adenauerzeit“) erstaunlicherweise vollkommen unterschlägt.

****************

Ein anderer Thyssen, der Probleme mit seiner Entnazifizierung gehabt haben sollte, dies aber nicht tat, war Heinrich’s Sohn Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Während sein Bruder Heini Thyssen im Deutschen Realgymnasium in Den Haag erzogen wurde, war Stephan auf das Internat Lyceum Alpinum in Zuoz, Schweiz, gegangen, wo die meisten Schüler aus der deutsch-sprachigen Schweiz, den Niederlanden und dem deutschen Reich stammten, bzw. Auslandsdeutsche waren. Demnach gab es in diesem Internat drei Schülerhäuser, mit den Namen „Teutonia“, „Orania“ und „Helvetia“. Nachdem er in Zurich und am Massachusetts Institute of Technology studiert hatte wurde er Assistent in einem Forschungslabor der Shell Petroleum Company in St. Louis. Dann schrieb er an der Universität Budapest seine Doktorarbeit und begann in der Lagerstättenforschung zu arbeiten.

Ab 1932, während er in Hannover lebte, arbeitete Stephan für die Seismos GmbH, eine Firma, die sich mit der Suche nach Bodenschätzen befasste. Sie wurde 1921 durch die Deutsch-Lux, Phoenix, Hoesch, Rheinstahl und die Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks AG gegründet. Derix schreibt: „Ab 1927 war die Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks AG, die wiederum zur 1926 gegründeten Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG gehörte, mit 50 Prozent der Anteile der Haupteigner des Unternehmens. Damit fiel Seismos unter Fritz Thyssens Teil des familialen Erbes. (…) In den 1920er Jahren waren die Messtrupps der Seismos für Ölfirmen wie Royal Dutch Shell oder Roxana Petroleum in Texas, Louisiana und Mexiko auf der Suche nach Öl. (…) Ihr Aktionsradius (weitete) sich auch auf den Nahen Osten, Südeuropa und England aus“.

1937 kaufte Heinrich Thyssen die Seismos für 1.5 Millionen Reichsmark und gliederte sie seinen Thyssenschen Gas- und Wasserwerken an. Während des Krieges, so Derix, war die Firma „an der Erschließung der Rohstoffe in den besetzten Gebieten beteiligt. (…) Beim Verlassen der Ostukraine im Zuge der Panzerschlacht von Kursk 1943 (musste sie) zahlreiches Gerät (…) zurücklassen“.

Hier liegt also einiges an Bedeutung vor für eine Firma, von der bisherige offizielle Thyssen Historien, wenn überhaupt, wenig Relevantes zu berichten hatten.

Und einiges an Bedeutung auch für den verschwiegenen Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, dessen Sohn Heini Thyssen kurz nach Kriegsende seinen Schweizer Rechtsanwalt Roberto van Aken zu folgender Falschaussage gegenüber der US amerikanischen Visabehörde veranlasste: „Seit dem Aufstieg der Nazis an die Macht, insbesondere seit 1938, waren Dr Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemiszas niederländische Unternehmen angehalten, die Aufrüstungsbestrebungen der Nazis zu unterlaufen.“ (Die Thyssen-Dynastie, Seite 265)

Es ist fast in diesem gleichen, verschleiernden Geiste, dass Derix immer noch die Tatsache verbirgt, dass Seismos während des Kriegs sein Hauptquartier von Hannover in den Harz verlegte, wo das Nazi Programm der Massenvernichtungswaffen (V-Waffen) sein Zentrum finden sollte.

Derix deckt auf, dass Stephan ein Mitglied des NS-Fliegerkorps war und bestätigt seine Rolle als förderndes Mitglied der SS. Seine politische Haltung war anscheinend als „ohne jeden Zweifel“ beschrieben worden. Doch bringt es Derix nicht fertig, seine Involvierung in eine weitere Firma, nämlich die Maschinen- und Apparatebau AG (MABAG) Nordhausen auch nur zu erwähnen, geschweige denn dabei ins Detail zu gehen, die ebenfalls im Harz ansässig war.

Wir hatten bereits herausgefunden, dass Stephan Thyssen in den ersten Kriegsjahren Aufsichtsratsvorsitzender der MABAG geworden war. Diese Firma hatte, zusammen mit der IG Farben, „die Anlage eines ausgedehnten Höhlen- und Tunnelsystems im Kohnstein, einem Berg bei Nordhausen (begonnen), ausgestattet mit Tanks und Pumpen (…) Ab Februar 1942 empfahl Reichminister für Bewaffnung und Munition Albert Speer, den Bau von Raketen mit allen Mitteln zu unterstützen. Das war ein extrem ehrgeiziger Waffenherstellungsplan und bedeutete erheblich mehr Aufträge für die MABAG, die unter Aufsicht der Wehrmacht jetzt auch Turbopumpen für die V-Waffen produzierte“. (Die Thyssen Dynastie, S. 203).

Wir hatten angenommen, dass Stephan’s Position als Vorsitzender der MABAG mit einer größeren Investition seitens seines Vaters zusammengehangen haben muss. Simone Derix spricht das Thema überhaupt nicht an, aber der Rechtsanwalt und Historiker Frank Baranowski hat ein sehr wichtiges Dokument gefunden und erklärt auf seiner Webseite:

„1940 stieß der Deutsche Erdöl-Konzern nach einem Wechsel an der Spitze alle seine Werke, die nicht direkt in den Rahmen der Mineralöl- und Kohlegewinnung passten ab, darunter auch die MABAG. Von der Deutschen Bank vermittelt, ging das Aktienkapital von einer Million RM in verschiedene Hände über. Die Mehrheit erwarb Rechtsanwalt und Notar Paul Langkopf aus Hannover (590.000 RM), und zwar vermutlich im Auftrag eines Mandanten, der ungenannt bleiben wollte. Kleinere Anteile hielten die beiden Außenstellen der Deutsche Bank in Leipzig (158.000 RM) und Nordhausen (14.000 RM) sowie Stephan Baron von Thyssen-Bornemisza in Hannover (50.000 RM). Am 14. September 1940 wählte die MABAG ihren neuen Aufsichtsrat: (…) Direktor Schirner (…), Paul Langkopf, Stephan Baron von Thyssen-Bornemisza und der Leipziger Bankdirektor Gustav Köllman (…) (Die MABAG sah sich ……..als reiner Rüstungslieferant und produzierte…… u.a. Granaten, Granatwerker …………und Turbopumpen für die A4-Raketen).“

Wie durch Zufall ist Paul Langkopf nun ausgerechnet ein Mann, dessen Dienste verschiedene Mitglieder der Familie über die Jahre in Anspruch genommen hatten. Es kann davon ausgegangen werden, dass der „anonyme“ Aktionär Stephans Vater Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza war. Die Geheimhaltung der Transaktion entspricht komplett seinem Stil. Und während Baranowskis Ansichten über die Verwendung von Zwangsarbeitern bei der MABAG und unsere auseinander gehen, so ist dieses von ihm erschlossenen Dokument doch ein weiterer Hinweis dafür, dass Heinrich während des Krieges definitiv 100% pro-Nazi war; während er sich anscheinend aus der Welt verabschiedet hatte und weit weg in seinem sicheren, Schweizer Hafen weilte, so wirkend, als hätte er mit gar nichts etwas zu tun.

Die große Simone Derix zieht es während dessen vor, sich auf relativ Triviales zu konzentrieren, so wie die Tatsache dass Stephan’s Mutter Margit ebenfalls, mit ihrem zweiten Mann, dem „germanophilen“, „antisemitischen“ Janos Wettstein von Westersheimb (der nach der Kriegswende 1943 seinen Job bei der Ungarischen Botschaft in Bern plötzlich verlor) während des Kriegs in der Schweiz lebte. Anscheinend hat sie sich nach dem Krieg für Stephans Ausreise aus Deutschland eingesetzt, und zwar bei keinem Geringeren als Heinrich Rothmund, der während des Kriegs für weite Teile der anti-jüdischen Asylpolitik der Schweiz verantwortlich war.

****************

Schließlich bearbeitet Simone Derix noch zwei Themen in ihrem Buch – die wir auch behandelt haben, wenn auch zu einem verschiedenen Grad -; nämlich 1.) Die Golddeponierung der Thyssens in London vor dem Krieg und was damit während bzw. nach dem Krieg geschah und 2.) Die Entfernung der Thyssenschen und niederländisch königlichen Aktienzertifikate aus der Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart in Rotterdam, deren Unterbringung in der August Thyssen Bank in Berlin während des Krieges und ihre Rückführung nach Rotterdam nach dem Krieg, in einer illegalen Aktion durch eine Niederländischen Militärmission unter der Tarnbezeichung „Operation Juliana“. Wir werden diese Themen angemessener bei unseren Besprechungen der Bände von Jan Schleusener, Harald Wixforth und Boris Gehlen analysieren.

In beiden Fällen spielten Mitglieder und Mitarbeiter der Thyssen Familie fragwürdige Rollen, indem sie ihre hochrangigen (diplomatischen und anderweitigen) Positionen ausnutzten, um es den Thyssens zu ermöglichen, in ihrer Gier nach grenzenlosem persönlichen Vorteil, eine Gastnation gegen die andere auszuspielen. Simone Derix führt ihre kritische Analyse hier nur so weit, dass sie sagt, diese Einmischungen hätten es kleineren Staaten wie den Niederlanden oder der Schweiz erlaubt, Siegermächte des zweiten Weltkriegs unter Druck zu setzen, um ihre eigenen nationalen Interessen am Vermögen der Thyssens zu wahren.

Während unser Buch ein mögliches „Handbuch der Revolution“ genannt worden ist, beschreibt Derix ihres als Model, bei dem „Die Thyssens (…) den Weg (…) für zentrale Suchrichtungen einer (…) Geschichte der Infrastruktur des Reichtums (weisen können)“. Sie lässt die Antriebskraft des „Neids“ à la Ralf Dahrendorf anklingen, während sie das Konzept der „Wut“ der Öffentlichkeit an der ständigen Inanspruchnahme rechtlicher Immunität durch die Super-Reichen außer Acht lässt, wie sie z.B. von Tom Wohlfahrt beschrieben worden ist.

Simone Derix’s Schreibstil ist sehr klar und während der Lesung im Historischen Kolleg in München verwandelte die sonore Stimme der speziell engagierten Sprecherin des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Passagen zu anscheinend tief in Rechtschaffenheit eingelegter Literatur. Aber diese Akademikerin, die von Professor Margit Szöllösi-Janze dem Publikum als „Spitzenforscherin“ angepriesen wurde, gibt sich selbst definitiv mehr Autorität darin, historische Urteile zu fällen, als es ihr gegenwärtig zusteht.

Während des nachfolgenden Podiumsgesprächs mit dem Historiker und Journalisten Dr Joachim Käppner von der Süddeutschen Zeitung, wies Derix die Konzepte von Macht und Schuld im Namen der Thyssens kategorisch zurück. Während sie dies tat, musste sie allerdings wiederholt durch Käppner vorangeleitet werden, um ihre äusserst stockenden Antworten zu fokussieren, die, nichtsdestotrotz, den Anschein gaben, vorher abgesprochen worden zu sein.

Wir hoffen, dass Simone Derix nicht die einzige Mitwirkende der Serie bleibt, die Antworten zu diesen Fragen formuliert – Aber dann vielleicht mit mehr Aufrichtigkeit, wenn nicht größerer Unabhängigkeit von der möglicherweise befangenen Fritz Thyssen Stiftung. |

Fritz Thyssen und Hermann Göring in Essen, copyright Stiftung Ruhr Museum Essen, Fotoarchiv  Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza und Hermann Göring beim Deutschen Derby, 1936, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Batthyany-Clan, ca. 1930er Jahre, dritter von links Ivan Batthyany, Ehemann von Margit Thyssen-Bornemisza, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Hendrik J. Kouwenhoven, Bevollmächtigter für Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, copyright Stadsarchief Rotterdam  Drei Thyssen Brüder vereint: von links Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, August Thyssen Junior, Fritz Thyssen, Villa Favorita, Lugano, September 1938, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield

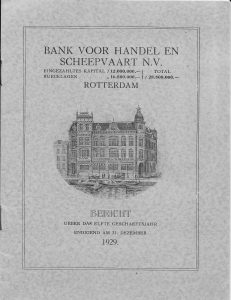

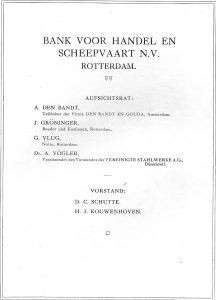

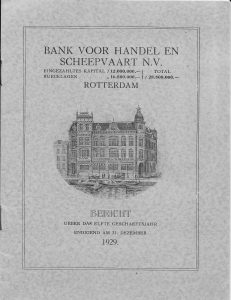

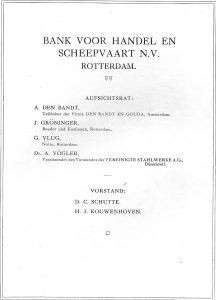

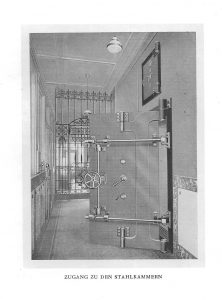

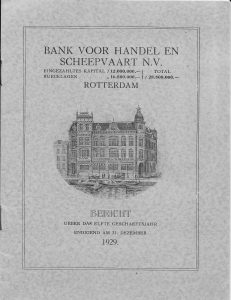

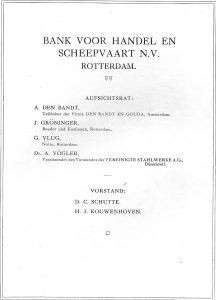

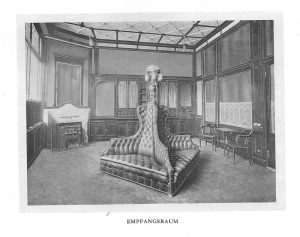

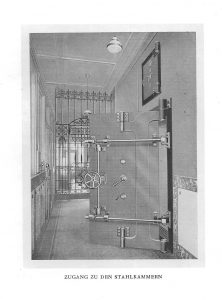

Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza mit Ehefrau Ingeborg, Hannover, ca. 1940er Jahre (Foto Alice Prestel-Hofmann, Hannover), copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, Jahresbericht 1930, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, Aufsichtsrat und Verwaltungsrat 1929, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, Schalterraum, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, 1929, Empfangsraum, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, 1929, Stahlkammern, copyright Archiv David R L Litchfield

|

|

Tags: "Operation Juliana", 7th Army Interrogation Center, A4-Raketen, Adolf Hitler, Akademiker, Aktien, Aktienzertifikate, Albert Speer, Alexis Leger, Alfried Krupp, Allen Dulles, alliierte Ermittler, altreich, Amelie Thyssen, Anita Zichy-Thyssen, arbeitende Reiche, Argentinien, Aristokratie, Aufenthaltsbewilligung, Augsburg, August Thyssen, August Thyssen Hütte, August Thyssen Junior, Ausländerausweis der Schweiz, Auslandsdeutsche, Auslandsvermögen, Ausreisegenehmigung, Bad Nauheim, Bad Wiessee, Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart, banking, Batthyany, Bayern, Berlin, Besatzungsmächte, Beschlagnahmung, besetzte Gebiete, Beteiligungen, Bismarck, Boris Gehlen, Bornemisza, Bosch, Broadway, Buenos Aires, Burton K. Wheeler, Conte Grande, Deusche Bank, Deutsch-Lux, Deutsch-Überseeische Handelsgesellschaft der Thyssenschen Werke mbH, deutsche Rüstungsindustrie, Deutsche Schule Den Haag, Deutschland, Devisenbeschränkungen, Die Thyssen-Dynastie, Die Thyssens als Kunstsammler, Dienlichkeitslegenden, Diplomatie, Distanz zwischen Herrschaft und Personal, Dr Amelung, Dr Joachim Käppner, Duisburg-Hamborn, Düsseldorf, Dustbin Zentrum für Wissenschaftler und Industrielle, Edmund Stinnes, England, Entnazifizierung, Erschließung der Rohstoffe, Ethik, Faminta AG, Faschist, Federico Zichy, Felix de Taillez, Finanzkapital, Flüchtlinge, förderndes Mitglied der SS, Forschung, Frank Baranowski, Friedrich Flick, Friedrich Thyssen, Fritz Thyssen, Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, Fritz und Heinrich Thyssen. Zwei Bürgerleben in der Öffentlichkeit, Fuchsjagd, Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks AG, Genua, Georg Thyssen, Gerda Henkel Stiftung, Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, Geschichtsschreibung, Golddeponierung, Granaten, Granatwerfer, Guy L'Estrange Ewen, Handels en Transport Maatschappij Vulcaan, Hannover, Hans Thyssen, Harald Wixforth, Harriman Building, Harz, Hauptwohnsitz, Heini Thyssen, Heini Thyssen-Bornemisza, Heinrich Blass, Heinrich Lübke, Heinrich Thyssen, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Helvetia, Hendrik J. Kouwenhoven, Henry Mowbray Howard, Hermann Göring, Hetzjagd, Hoesch, Hohenzollern, Holland American Investment Corporation, Hundemeute, IG Farben, Internationalisierung, Jan Schleusener, Janos Wettstein von Westersheimb, Johannes Bähr, Johannes Gramlich, Jörg Lesczenski, Josef Thyssen, Julius Thyssen, Kapitalanlagen, Kapitalflucht, Kaszony Stiftung, Kohnstein, Königin Wilhelmina, Königstein, Konzentrationslager, Kornwestheim, Kriegsverbrechen, Krupp, Lagerstättenforschung, Landesverrat, Lebensstil, London, Louisiana, Luftangriff, Lugano, Lyceum Alpinum, MABAG, Macht, Machtergreifung, Management, Manager Magazin, Marineministerium, Maschinen- und Apparatebau, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massenvernichtungswaffen, Mausoleum, Mexiko, Mineralöl- und Kohlegewinnung, Moral, Mülheim-Kettwig, München, Nationalsozialismus, Neid, Neubabelsberg, neureich, neutrale Länder, New York, Nordhausen, NSDAP, Nürnberg, Nürnberger Nachfolgeprozesse, Oberursel, Offshore-Instrumente, Opfer, Orania, Panzerschlacht von Kursk, Paris, Paul Langkopf, Pelzer Stiftung, Phoenix, Plagiarisierung, Professor Manfred Rasch, Professor Margit Szöllösi-Janze, propaganda, public relations, Quandt, Quellenbestand, Ralf Dahrendorf, Raoul Dautry, Reichtum, Rheinstahl, Robert Kempner, Roberto van Aken, Rohmaterialhandel, Rohstoffankäufe, Rotterdam, Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor, Roxana Petroleum, Royal Dutch Shell, Ruhrgebiet, Rüstungslieferant, Sammlung Schloss Rohoncz, Sanatorium, Scheveningen, Schloss Kransberg, Schloss Landsberg, Schuld, Schweiz, Schweizerische Kreditanstalt, Seismos GmbH, Shell Petroleum Company, Siemens, Simone Derix, St. Louis, Staatsangehörigkeit, Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza, Steuerflucht, Steuern, Steueroasen, Steuerumgehung, Stiftung Sammung Schloss Rohoncz, Stiftung zur Industriegeschichte Thyssen, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Tarnbezeichung, Täter, Teutonia, Texas, Thurn und Taxis, Thyssen & Co, Thyssen Biografen, Thyssen in der Adenauerzeit, Thyssen Konzern, Thyssen Organisation, Thyssen-Bornemisza Gruppe, Thyssen-Mythos, ThyssenKrupp Konzern-Archiv, Tom Wohlfahrt, transnationales Leben, Transparenz, Transportkontor Vulkan GmbH, Trust Department, Turbopumpen, Übersee-Trust Vaduz, ultravermögend, ungarische Staatsbürgerschaft, Ungarn, Union Banking Corporation, Universität Budapest, US Gefangenenlager Seckenheim, US-Amerikanische Kredite, US-Senator, V-Waffen, Vaterlandsliebe, Vereinigte Stahlwerke, Vermögen, Vermögensverwaltungsgesellschaft, Villa Favorita, Volkswohl, Vulcaan Coal Company, Waffen, Wehrmacht, Wittelsbach, Wut, Zichy, Zuoz, Zurich, Zwangsarbeit bei Thyssen, Zwangsarbeiter

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Art, Thyssen Corporate, Thyssen Family Comments Off on Buchrezension: Thyssen im 20. Jahrhundert – Band 4: ‘Die Thyssens. Familie und Vermögen’, von Simone Derix, erschienen im Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn, 2016 (scroll down for english version)

Monday, March 5th, 2018

| Reviewing this book is a huge aggravation to us, as so much of it has been derived from our groundbreaking work on the Thyssens, published a decade earlier, for which the author grants us not a single credit. It is surprising that Simone Derix does not have the respect for professional ethics to acknowledge our historiographic contribution; especially since she stated in a 2009 conference that non-academic works, whilst creating feelings of fear amongst academics of losing their prerogative to interpret history, are taking on increasing importance.

Ms Derix herself is not the fearful type of course, though somewhat hypocritical. She appears to be preemptively obedient and committed to pleasing her presumably partisan paymasters, in the form of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. Alas, she is clearly not the smartest person either; writing, for instance, that Heinrich Lübke, Director of the August Thyssen Bank (he died in 1962), was the same Heinrich Lübke who was President of Germany (in that position until 1969).

But Ms Derix’s intellectual shortcomings are much more serious than simple factual errors, which should, in any case, have been picked up by at least one of her two associate writers, three project leaders, four academic mentors and six research assistants. She is in all seriousness trying to convince us that research into the lives of wealthy persons is a brand new branch of academia, and that she is its most illustrious, pioneering proponent. Does she not know that recorded history has traditionally been by the rich, of the rich and for the rich only? Has she forgotten that even basic reading and writing were privileges of the few until some hundred and fifty years ago?

At the same time, contrary to us, Derix does not appear to have had any first hand experience of exceptionally rich people at all, particularly Thyssens. Her sponsorship, earlier in her studies, by the well-endowed Gerda Henkel Foundation, was presumably an equally ‘arm’s length’ relationship. Rich people only mix with rich people, and unless Derix got paid by the word, there is no evidence that she ever in any way qualified for serious comment on their modus operandi.

What is new, of course, is that feudalism has been swept away and replaced by democratic societies, where knowledge is broadly accessible and equality before the law is paramount. Yes, her assertion that super-rich people’s archives are difficult to access is true. They only ever want you to know glorious things about them and keep the realities cloaked behind their outstanding wealth. To suggest that this series is being issued because the Thyssens have suddenly decided to engage in an exercise of honesty, generously letting official historians browse their most private documents, however, is ludicrous. The only reason why Simone Derix is revealing some controversial facts about the Thyssens is because we already revealed them. The difference is that she repackages our evidence in decidedly positive terms, so as to comply with the series’ overall damage limitation program.

Thus, Derix seems to believe she can run with the fox and hunt with the hounds; a balancing act made considerably easier by her pronouncement, early on, that any considerations of ethics or morality are to be categorically excluded from her study. The fact that the Thyssens camouflaged their German companies (including those manufacturing weapons and using forced labour) behind international strawmen, with the benefit of facilitating the large-scale evasion of German taxes, is re-branded by Derix as being a misleading description ‘made from a state perspective’ and which ‘tried to establish a desired order rather than depict an already existing order’. As if ‘the state’, as we democrats understand it, is some kind of devious entity that needs fending off, rather than the collective support mechanism of all equal, law-abiding citizens.

It is just one of the many statements that appears to show how much the arguably authoritarian mindset of her sponsors may have rubbed off on her. The fact that academics employed by publicly funded universities should be used thus as PR-agents for the self-serving entities that are the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the Thyssen Industrial History Foundation and the ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archive is highly questionable by any standards, but particularly by supposedly academic ones. Especially when they claim to be independent.

****************

In Derix’s world, the Thyssens are still (!) mostly referred to as ‘victims’, ‘(tax) refugees’, ‘dispossessed’ and ‘disenfranchised’, even if she admits briefly, once or twice in 500 pages, that ‘in the long-term it seems that they were able always to secure their assets and keep them available for their own personal needs’.

As far as the Thyssens’ involvement with National Socialism is concerned, she calls them ‘entangled’ in it, ‘related’ to it, being ‘present’ in it and ‘living in it’. With two or three exceptions they are never properly described as the active, profiting contributors to the existence and aims of the regime. Rather, as in volume 2 (‘Forced Labour at Thyssen’), the blame is again largely transferred to their managers. This is very convenient for the Thyssens, as the families of these men do not have the resources to finance counter-histories to clear their loved ones’ names.

But for Simone Derix to say that ‘from the perspective of nation states these (Thyssen managers) had to appear to be hoodlums’ really oversteps the boundaries of fair comment. The outrageousnness of her allegation is compounded by the fact that she fails to quote evidence, as reproduced in our book, showing that allied investigators made clear reference to the Thyssens themselves being the real perpetrators and obfuscators.

Yet still, Derix purports to be invoking German greatness, honour and patriotism in her quest for Thyssen gloss. She alleges bombastically that the mausoleum at Landsberg Castle in Mülheim-Kettwig ‘guarantees (the family’s) presence and attachment to the Ruhr’ and that there is an ‘indissoluble connection between the Thyssen family, their enterprises, the region and their catholic faith’. But she fails to properly range them alongside the industrialist families of Krupp, Quandt, Siemens and Bosch, preferring to surround their name hyperbolically with those of the Bismarck, Hohenzollern, Thurn und Taxis and Wittelsbach ruling dynasties.

In reality, many Thyssen heirs chose to turn their backs on Germany and live transnational lives abroad. Their mausoleum is not even accessible to the general public. Contrary to what Derix implies, the iconic name that engenders such a strong feeling of allegiance in Germany is that of the public Thyssen (now ThyssenKrupp) company alone, as one of the main national employers. This has nothing whatsoever to do with any respect for the descendants of the formidable August Thyssen, most of whom are, for reason of their chosen absence, completely unknown in the country.

****************

In this context, it is indicative that Simone Derix categorises the Thyssens as ‘old money’, as well as ‘working rich people’. But while in the early 19th century Friedrich Thyssen was already a banker, it was only his sons August (75% share) and Josef (25% share), from 1871 onwards (and with the ensuing profits from the two world wars) who created through their relentless work, and that of their employees and workers, the enormous Thyssen fortune. Their equal was never seen again in subsequent Thyssen generations.

Thus the Thyssens became ‘ultra-rich’ and were completely set apart from the established aristocratic-bourgeois upper class. They could hardly be called ‘old money’ and neither could their heirs, despite trying everything in their power to adopt the trappings of the aristocracy (which beggars the question why volume 6 of the series is called ‘Fritz and Heinrich Thyssen – Two bourgeois lives in the public eye’). This included marrying into the Hungarian, increasingly faux aristocracy, whereby, even Derix has to admit, by the 1920s every fifth Hungarian citizen pretended to be an aristocrat.

The line of Bornemiszas, for instance, which Heinrich married into, were not the old ‘ruling dynastic line’ that Derix still pretends they were. The Thyssen-Bornemiszas came to be connected with the Dutch royals not because Heinrich’s wife Margit was such a (self-styled) ‘success’ at court, but because the Thyssens had important business interests in that country. Thus Heinrich became a banker to the Dutch royal household, as well as a personal friend of Queen Wilhelmina’s husband Prince Hendrik.

The truth is: apart from such money-orientated connections, neither the German nor the English or any other European nobility welcomed these parvenus into their immediate ranks (religion too played a role, of course, as the Thyssens were and are catholics). Until, that is, social conventions had moved on enough by the 1930s and their daughters were able to marry into the truly old Hungarian dynasties of Batthyany and Zichy.

But until that time, based on their outstanding wealth, this did not stop the brothers from adopting many of the domains of grandeur for themselves. Fritz Thyssen, according to Derix, even spent his time in the early 1900s importing horses from England, introducing English fox hunting to Germany and owning a pack of staghounds. He also had his servant quarters built lower down from his own in his new country seat, specifically to signal class distinction.

These are indeed remarkable new revelations showing that the traditional image put out by the Thyssen organisation of bad cop German, ‘temporarily’ fascist industrialist Fritz Thyssen, good cop Hungarian ‘nobleman’ Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza is even more misleading than we always thought.

****************

Truly lamentable are Derix’s attempts to portray Fritz Thyssen as a devout, christian peacenik and centrist party member. And so are her lengthy contortions in presenting Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza as the perfectly assimilated Hungarian country squire. She does, however, report that Heinrich’s wife had stated he did not speak a word of the language, which does not stop Felix de Taillez in volume 6 writing that he did speak Hungarian. ‘If you can’t beat them, confuse them’ was Heini Thyssen’s motto. Clearly, it has also become the motto of these Thyssen-financed academics.

Meanwhile, Derix’s book is the first work supported by the Thyssen organisation to confirm that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza did retain his German (then Prussian) citizenship. She also does venture to state that his adoption of the Hungarian nationality ‘might’ have been ‘strategic’. But these gems of truthfulness are swamped under the fountains of her gushing propaganda designed to make the second generation Thyssens look better than they were. This includes her development of August Junior’s role from black sheep of the family to committed businessman.

On the other hand, the author still fails to explain any business-related details on the much more important Heinrich Thyssen’s life in England at the turn of the century (cues: banking and diplomacy). How exactly did the family come to be closely acquainted with the likes of Henry Mowbray Howard (British liaison officer at the French Naval Ministry) or Guy L’Estrange Ewen (special envoy to the British royals)? A huge chance of genuine transparency was wasted here.

Derix also fails to draw attention to the fact that the August Thyssen and Josef Thyssen branches of the family developed in very different ways. August’s heirs exploited, left and betrayed Germany and were decidedly ‘nouveau riche’, except for Heinrich’s son Heini Thyssen-Bornemisza and his son Georg Thyssen, who really did involve themselves in the management of their companies.

By contrast, Josef’s heirs Hans and Julius Thyssen stayed in Germany (respectively were prepared to return there in the 1930s from Switzerland when foreign exchange restrictions came into force), paid their taxes, worked in the Thyssen Konzern before selling out in the 1940s, pooling their resources and adopting careers in the professions. Only the Josef Thyssen side of the family is listed in the German Manager Magazine Rich List; but for unexplained reasons Derix leaves these truly ‘working rich’ Thyssens largely unmentioned in her book.

****************

Fortunately, Derix does not concentrate all her efforts in creative fiction and plagiarisation, but manages to provide at least some substantive politico-economic facts as well. So she reveals that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza was a member of the supervisory board of the United Steelworks of Düsseldorf until 1933, i.e. until after Adolf Hitler’s assumption of power. This, combined with her statement that ‘Heinrich seems to have orientated himself towards Berlin on a permanent basis as early as 1927/8 (from Scheveningen in The Netherlands)’ pokes a hole in one of the major Thyssen convenience legends, that of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza having had his main residence in neutral Switzerland from 1932 onwards (i.e. conveniently from before Hitler’ assumption of power; having ‘left Germany just in time’); though this does not stop Derix from subsequently repeating that fallacy just the same (- ‘If you can’t beat them, confuse them’-).

Fact is that, despite buying Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland in 1932, Heinrich Thyssen continued to spend the largest amounts of his time living a hotel life in a permanent suite in Berlin and elsewhere and also kept a main residence in Holland (where Heini Thyssen grew up almost alone, except for the staff). His Ticino lawyer Roberto van Aken had to remind him in 1936 that he still had not applied for permanent residency in Switzerland. It was not until November 1937 that Heinrich Thyssen and his wife Gunhilde received their Swiss foreigner passes (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, page 116).

Derix also readjusts the old Thyssen myth that Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza went their separate ways in business as soon as they inherited from their father, who died in 1926. We always said that the two brothers remained strongly interlinked until well into the second half of the 20th century. And hey presto, here we have Simone Derix alleging now that ‘historians so far have always assumed that the separation had been concluded by 1936’. She adds ‘despite all attempts at separating the shares of Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, the fortunes of Fritz and Heinrich remained interlocked (regulated contractually) well into the time after the second world war’.

But it is her next sentence that most infuriates: ‘Obviously it was very difficult for outsiders to recognise this connection’. The truth of the matter is that the situation was opaque because the Thyssens and their organisation went to extraordinary lengths and did everything in their power to obfuscate matters, particularly as it meant hiding Fritz Thyssen’s and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s joint involvement in supporting the Nazi regime.

****************

Amongst the Thyssens’ many advisors, the author introduces Dutchman Hendrik J Kouwenhoven as the main connecting link between the brothers, who ‘opened up opportunities and thought up financial instruments’. He worked from 1914 at the family’s Handels en Transport Maatschappij Vulcaan and then at their Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart (BVHS) in Rotterdam from its official inception in 1918 to his sacking by Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza during the second world war.

The asset management or trust company of BVHS was called Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor (RTK), which Derix describes as ‘repository for the finance capital of the Thyssen enterprises, as well as for the Thyssens’ private funds’. She does not say when it was created. ‘Its offices and all the important papers that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza had lodged (at RTK) were all destroyed in a German aerial bombardment of Rotterdam on 14.05.1940’, according to Derix. To us this sounds like a highly suspicious piece of information.

Of the files of BVHS she curtly says that ‘a complete set of source materials is not available’. How convenient, especially since no-one outside the Thyssen organisation will ever be able to verify this claim truly independently; or at least until the protective mantle of Professor Manfred Rasch, head of the ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archive, retires.

Derix alludes to ‘the early internationalisation of the Thyssen Konzern from 1900’, ascribing her knowledge of its bases in raw material purchases and the implementation of a Thyssen-owned trading and transport network to Jörg Lesczenski, who published two years after us (and whose work, like that of Derix herself, was backed by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation). But she leaves cross-references aside concerning the first tax havens (including that of The Netherlands) which were set up in the outgoing 19th century, conveniently referring this area to ‘research that should be carried out in the future’.

Derix names the 1906 Transportkontor Vulkan GmbH Duisburg-Hamborn with its Rotterdam branch (see above) and the 1913 Deutsch-Überseeische Handelsgesellschaft der Thyssenschen Werke mbH of Buenos Aires (by the way: to this day ThyssenKrupp AG is a major trader in raw materials). She also states that American loans to the Thyssen Konzern started in 1919 via the ‘Vulcaan Coal Company’ (failing to mention that this company was based in London).

****************

According to Derix, August Thyssen began transferring his shares in the Thyssen companies to his sons Fritz and Heinrich in 1919, first those of Thyssen & Co. and from 1921 onwards those of the August Thyssen smelting works. She then adds that existing Thyssen institutions outside of Germany were used in order to carry out this transfer.

From 1920 onwards, Fritz Thyssen began to buy real estate in Argentina. Meanwhile, the Thyssens’ Union Banking Corporation (UBC), founded in 1924 in the Harriman Building on New York’s Broadway, is described solely in the language of the ‘transnational dimension of the Thyssens’ financial network’ and as being ‘the American branch of the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart’.

We had already detailed in our book how Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, via Hendrik Kouwenhoven, set up in Switzerland the Kaszony Family Foundation in 1926 to lodge his inherited participations and the Rohoncz Collection Foundation in 1931 to place art works he bought as easily movable capital investments from 1928 onwards. Now Derix writes that the Rohoncz Foundation too was founded in 1926. This is astonishing, since it means that this entity was set up a whole two years prior to Heinrich Thyssen buying the first painting to find its way into what he called the ‘Rohoncz Castle Collection’ (despite the fact that none of the pictures ever went anywhere near his Hungarian, then Austrian castle, in which he had stopped living in 1919).

The timing of the creation of this offshore instrument just proves how contrived Heinrich’s reinvention as a ‘fine art connaisseur and collector’ really was.

Derix even freely admits that these Thyssen family foundations were ‘antagonists of states and governments’. However, just like Johannes Gramlich in volume 3 (‘The Thyssens as Art Collectors’), she too leaves the logistics of the transfer of some 500 paintings by Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza into Switzerland in the 1930s completely unmentioned, including the fact that this represented a method of massive capital flight out of Germany. The associated topics of tax evasion and tax avoidance stay completely off her academic radar; ignoring our documented proof.

****************

In another bold rewriting of official Thyssen history the author states that the Thyssen brothers frequently acted in parallel in their financial affairs. And so it was that the Pelzer Foundation and Faminta AG came to be created , by Kouwenhoven, in Switzerland, on behalf of Fritz Thyssen and his immediate family. (Derix is hazy about exact dates. We published: 1929 for Faminta AG and the late 1930s for the Pelzer Foundation).

Derix points out that these two instruments also allowed secret transactions between the Thyssen brothers. She adds enigmatically that ‘Faminta protected the foreign assets of the August Thyssen smelting works from a possible confiscation by the German authorities’, whilst withholding any reference to a time scale of when such a confiscation might have been on the cards (is she suggesting a possibility prior to Fritz Thyssen’s flight in September 1939, i.e. anytime during the period 1929-1939?).

At the same time, in the 1920s, Fritz and Amelie Thyssen established a firm base in the south of the German Reich, namely in Bavaria – far away from the Thyssen heartland of the Ruhr – which Derix brands as a fact which has ‘so far been almost completely ignored by historians’. Of course, not only was this most royalist of German states close to Switzerland, but it was also, at that time, the cradle of the Nazi movement. Adolf Hitler also much preferred Munich to Berlin.

All the family’s financial instruments, meanwhile, continued to be administrated by Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor in The Netherlands. ‘These new Thyssen banks, companies, holdings and foundations created since the 1920s were connected to the Thyssen industrial enterprises (in Germany) through participations’, Derix continues.

These enterprises etc. were also supportive of the rising Nazi movement of course, such as when their Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart around 1930 demonstrably made a loan of some 350,000 RM to the Nazi party, at a time when both Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza had controlling interests in BVHS.

According to Derix, it was starting in 1930 that Heinrich Thyssen sold his shares in the United Steelworks to Fritz while Fritz sold his Dutch participations to Heinrich and as a result Heinrich Thyssen alone was in control of the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart from 1936 onwards.

Specifically, it was a Thyssen entity called Holland-American Investment Corporation (HAIC) which facilitated Fritz Thyssen’s capital flight from Germany. According to Derix, ‘(in the autumn of 1933, the Pelzer Foundation acquired) shares in HAIC from Fritz and therefore his Dutch participations which were pooled therein. This was done in agreement with the German authorities who knew of HAIC. But in 1940, the Germans found out that there was a considerable discrepancy between the 1,5 million Reichsmark of Dutch participations held in HAIC as had been stated and the actual, true value, which turned out to be 100 to 130 million RM.’

This is staggering, as the modern day equivalent is many hundreds of millions of Euros!

Considering that Heinrich’s wife stated that he had taken some 200 million Swiss Francs of his assets into neutral countries, this would mean that, together, the Thyssen brothers possibly succeeded in extracting from Germany the cash equivalent of close to the complete monetary value of the Thyssen enterprises! This is not, however, a conclusion drawn by Simone Derix.

One begins to wonder what there was actually left to confiscate from Fritz Thyssen once he fled Germany at the onset of war in 1939. Derix admits that his flight happened not least because he preferred to complete his self-interested financial transactions from the safety of Switzerland, with the help of Heinrich Blass at Credit Suisse in Zurich.

Although we had managed to unearth several leads, we did not know that the real overall extent of the Thyssen brothers’ capital flight was quite this drastic. For Simone Derix to point this out on behalf of the Thyssen organisation is significant; even if she fails to draw any appropriate conclusions, as they would most likely be at odds with her blue-sky remit.

Truly, and in the words of the far more experienced Harald Wixforth no less: for these ‘mega-capitalist(s) (…) the profit of their enterprises (i.e. their own) always assumed far greater priority than the public’s welfare’.

Needless to say that we await Harald Wixforth’s and Boris Gehlen’s volumes on the Thyssen Bornemisza Group 1919-1932, respectively 1932-1947 with great interest.

****************

In this readjusted official light, Derix’s admission that Fritz and Amelie Thyssen’s ‘expropriation’ in late 1939 ‘did not directly result in any curtailment of their way of life’ no longer comes as any surprise.

The author also finally reveals for the first time official departure details of Fritz Thyssen’s daughter Anita, her husband Gabor and their son Federico Zichy to Argentina. Apparently they travelled from Genua, sailing on 17.02.1940 on board the ship Conte Grande, bound for Buenos Aires. In order to provide her with befitting financial support, shares in Faminta AG had been transferred to the Übersee-Trust of Vaduz shortly beforehand, of which Anita Zichy-Thyssen, a Hungarian national, was the sole beneficiary.

Derix then states that by April 1940, Fritz Thyssen ‘used his political knowledge on the German Reich and the German armaments industry as an asset that he could use in exchange for support for his personal wishes’. But what exactly were those wishes? The hubristically delusional Fritz obviously thought he could get rid of Hitler as easily as he had helped him get into power. For this, he was prepared to share German state secrets with French Foreign Minister Alexis Leger and Armament Minister Raoul Dautry in Paris. But for Derix, rather than being anything as contentious as active treason or an expression of power, his behaviour is nothing more than an ultra-rich man’s legitimate right to express his elevated lifestyle choices.

While all previous Thyssen biographers, apart from us, have purported that Fritz and Amelie Thyssen suffered tremendous ‘excrutiations’ during their time in concentration camps, Derix confirms our information that they spent most of their German captivity in the comfortable, private sanatorium of Dr Sinn in Berlin-Neubabelsberg. She writes that they were kept there ‘on Hitler’s personal orders’ and ‘on trust’, though Fritz and Heinrich’s personal friend Hermann Göring, during his post-war allied interrogations, stated that their privileged treatment had been down to his initiative. After Neubabelsberg, they were taken to different concentration camps, but Derix is now forced to admit that they enjoyed ‘a special status’ which is retraceable ‘for each and every location’. Which makes one wonder, why German historians previously felt the need to misrepresent these facts.

Derix’s list of Fritz Thyssen’s allied, post-war interrogations is particularly noteworthy. It illustrates the seriousness in which he was considered to have been guilty of (albeit blue collar) war crimes, which should have been punishable by incarceration:

In July 1945 he was taken to Schloss Kransberg near Bad Nauheim, namely to the so-called ‘US/UK Dustbin Centre for scientists and industrialists’. In August, he went on to Kornwestheim before being taken, in September, to the 7th Army Interrogation Center in Augsburg.

Derix also vagely asserts that Fritz Thyssen was interrogated at some point ‘in 1945’ by Robert Kempner, chief prosecutor of the Nuremberg trials.

Thyssen suffered a collapse and had to go into medical care. He was taken to the US prisoners’ camp of Seckenheim, then to Oberursel. His health deteriorated. From April to November 1946 he went through various hospitals and convalescent homes between Königstein (where he made a surprise recovery) and Oberursel. From November 1946 onwards, he was at the Nuremberg follow-up trials as a witness (one presumes in the cases of Alfried Krupp and Friedrich Flick amongst others), while receiving continuous hospital treatment in Fürth.

On 15.01.1947 Fritz Thyssen was released to join his wife Amelie in Bad Wiessee. This was followed by his German denazification proceedings in Königstein, where he and Amelie lived at the sanatorium of Dr Amelung. In that court, as befitting his insincere character, Fritz Thyssen described himself as penniless.

Meanwhile, according to Derix, Anita Zichy-Thyssen made contact with Edmund Stinnes, who lived in the US and his brother-in-law Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, a close collaborator of US-secret service chief Allen Dulles. In the spring of 1947, ‘hoping to facilitate exit permits for her parents to go to America’, she met former US-senator Burton K Wheeler in Argentina, who travelled to Germany in 1948 ‘in order to help Fritz Thyssen out of his denazification problems’. It is certainly an aspect of high-level influence which we documented even more intensively, but which, astonishingly, Johannes Bähr in volume 5 (‘Thyssen in the Adenauer Period’) of the series has totally rejected.

****************

Another Thyssen who should have had problems with his denazification, but didn’t, was Heinrich’s son Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza.

While his brother Heini Thyssen went to the German school in The Hague, Stephan had boarded at the Lyceum Alpinum in Zuoz, Switzerland, where most pupils were from German speaking Switzerland, The Netherlands and the German Reich, respectively were Germans living abroad. Consequently, the school ran three houses named ‘Teutonia’, ‘Orania’ and ‘Helvetia’. After studying chemistry in Zurich and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he became an assistant at a research laboratory of the Shell Petroleum Company in St Louis. He then wrote his dissertation at Budapest University and began working in natural resources deposit research.

Since 1932, whilst living in Hanover, Stephan worked for Seismos GmbH, a prospecting company founded in 1921 by Deutsch-Lux, Phoenix, Hoesch, Rheinstahl and Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks AG. Derix writes: ‘From 1927 Gelsenkirchener, which belonged to the United Steelworks founded in 1926, was the main shareholder, holding 50% of the shares. This means Seismos came under Fritz Thyssen’s part of the family inheritance. (…) In the 1920s, prospecting groups of Seismos worked for oil companies such as Royal Dutch Shell or Roxana Petroleum in Texas, Louisiana and Mexico, looking for Oil. (…) Its radius then extended to the Near East, South-Eastern Europe and England’.