Posts Tagged ‘Bavaria’

Monday, March 5th, 2018

| Reviewing this book is a huge aggravation to us, as so much of it has been derived from our groundbreaking work on the Thyssens, published a decade earlier, for which the author grants us not a single credit. It is surprising that Simone Derix does not have the respect for professional ethics to acknowledge our historiographic contribution; especially since she stated in a 2009 conference that non-academic works, whilst creating feelings of fear amongst academics of losing their prerogative to interpret history, are taking on increasing importance.

Ms Derix herself is not the fearful type of course, though somewhat hypocritical. She appears to be preemptively obedient and committed to pleasing her presumably partisan paymasters, in the form of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. Alas, she is clearly not the smartest person either; writing, for instance, that Heinrich Lübke, Director of the August Thyssen Bank (he died in 1962), was the same Heinrich Lübke who was President of Germany (in that position until 1969).

But Ms Derix’s intellectual shortcomings are much more serious than simple factual errors, which should, in any case, have been picked up by at least one of her two associate writers, three project leaders, four academic mentors and six research assistants. She is in all seriousness trying to convince us that research into the lives of wealthy persons is a brand new branch of academia, and that she is its most illustrious, pioneering proponent. Does she not know that recorded history has traditionally been by the rich, of the rich and for the rich only? Has she forgotten that even basic reading and writing were privileges of the few until some hundred and fifty years ago?

At the same time, contrary to us, Derix does not appear to have had any first hand experience of exceptionally rich people at all, particularly Thyssens. Her sponsorship, earlier in her studies, by the well-endowed Gerda Henkel Foundation, was presumably an equally ‘arm’s length’ relationship. Rich people only mix with rich people, and unless Derix got paid by the word, there is no evidence that she ever in any way qualified for serious comment on their modus operandi.

What is new, of course, is that feudalism has been swept away and replaced by democratic societies, where knowledge is broadly accessible and equality before the law is paramount. Yes, her assertion that super-rich people’s archives are difficult to access is true. They only ever want you to know glorious things about them and keep the realities cloaked behind their outstanding wealth. To suggest that this series is being issued because the Thyssens have suddenly decided to engage in an exercise of honesty, generously letting official historians browse their most private documents, however, is ludicrous. The only reason why Simone Derix is revealing some controversial facts about the Thyssens is because we already revealed them. The difference is that she repackages our evidence in decidedly positive terms, so as to comply with the series’ overall damage limitation program.

Thus, Derix seems to believe she can run with the fox and hunt with the hounds; a balancing act made considerably easier by her pronouncement, early on, that any considerations of ethics or morality are to be categorically excluded from her study. The fact that the Thyssens camouflaged their German companies (including those manufacturing weapons and using forced labour) behind international strawmen, with the benefit of facilitating the large-scale evasion of German taxes, is re-branded by Derix as being a misleading description ‘made from a state perspective’ and which ‘tried to establish a desired order rather than depict an already existing order’. As if ‘the state’, as we democrats understand it, is some kind of devious entity that needs fending off, rather than the collective support mechanism of all equal, law-abiding citizens.

It is just one of the many statements that appears to show how much the arguably authoritarian mindset of her sponsors may have rubbed off on her. The fact that academics employed by publicly funded universities should be used thus as PR-agents for the self-serving entities that are the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the Thyssen Industrial History Foundation and the ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archive is highly questionable by any standards, but particularly by supposedly academic ones. Especially when they claim to be independent.

****************

In Derix’s world, the Thyssens are still (!) mostly referred to as ‘victims’, ‘(tax) refugees’, ‘dispossessed’ and ‘disenfranchised’, even if she admits briefly, once or twice in 500 pages, that ‘in the long-term it seems that they were able always to secure their assets and keep them available for their own personal needs’.

As far as the Thyssens’ involvement with National Socialism is concerned, she calls them ‘entangled’ in it, ‘related’ to it, being ‘present’ in it and ‘living in it’. With two or three exceptions they are never properly described as the active, profiting contributors to the existence and aims of the regime. Rather, as in volume 2 (‘Forced Labour at Thyssen’), the blame is again largely transferred to their managers. This is very convenient for the Thyssens, as the families of these men do not have the resources to finance counter-histories to clear their loved ones’ names.

But for Simone Derix to say that ‘from the perspective of nation states these (Thyssen managers) had to appear to be hoodlums’ really oversteps the boundaries of fair comment. The outrageousnness of her allegation is compounded by the fact that she fails to quote evidence, as reproduced in our book, showing that allied investigators made clear reference to the Thyssens themselves being the real perpetrators and obfuscators.

Yet still, Derix purports to be invoking German greatness, honour and patriotism in her quest for Thyssen gloss. She alleges bombastically that the mausoleum at Landsberg Castle in Mülheim-Kettwig ‘guarantees (the family’s) presence and attachment to the Ruhr’ and that there is an ‘indissoluble connection between the Thyssen family, their enterprises, the region and their catholic faith’. But she fails to properly range them alongside the industrialist families of Krupp, Quandt, Siemens and Bosch, preferring to surround their name hyperbolically with those of the Bismarck, Hohenzollern, Thurn und Taxis and Wittelsbach ruling dynasties.

In reality, many Thyssen heirs chose to turn their backs on Germany and live transnational lives abroad. Their mausoleum is not even accessible to the general public. Contrary to what Derix implies, the iconic name that engenders such a strong feeling of allegiance in Germany is that of the public Thyssen (now ThyssenKrupp) company alone, as one of the main national employers. This has nothing whatsoever to do with any respect for the descendants of the formidable August Thyssen, most of whom are, for reason of their chosen absence, completely unknown in the country.

****************

In this context, it is indicative that Simone Derix categorises the Thyssens as ‘old money’, as well as ‘working rich people’. But while in the early 19th century Friedrich Thyssen was already a banker, it was only his sons August (75% share) and Josef (25% share), from 1871 onwards (and with the ensuing profits from the two world wars) who created through their relentless work, and that of their employees and workers, the enormous Thyssen fortune. Their equal was never seen again in subsequent Thyssen generations.

Thus the Thyssens became ‘ultra-rich’ and were completely set apart from the established aristocratic-bourgeois upper class. They could hardly be called ‘old money’ and neither could their heirs, despite trying everything in their power to adopt the trappings of the aristocracy (which beggars the question why volume 6 of the series is called ‘Fritz and Heinrich Thyssen – Two bourgeois lives in the public eye’). This included marrying into the Hungarian, increasingly faux aristocracy, whereby, even Derix has to admit, by the 1920s every fifth Hungarian citizen pretended to be an aristocrat.

The line of Bornemiszas, for instance, which Heinrich married into, were not the old ‘ruling dynastic line’ that Derix still pretends they were. The Thyssen-Bornemiszas came to be connected with the Dutch royals not because Heinrich’s wife Margit was such a (self-styled) ‘success’ at court, but because the Thyssens had important business interests in that country. Thus Heinrich became a banker to the Dutch royal household, as well as a personal friend of Queen Wilhelmina’s husband Prince Hendrik.

The truth is: apart from such money-orientated connections, neither the German nor the English or any other European nobility welcomed these parvenus into their immediate ranks (religion too played a role, of course, as the Thyssens were and are catholics). Until, that is, social conventions had moved on enough by the 1930s and their daughters were able to marry into the truly old Hungarian dynasties of Batthyany and Zichy.

But until that time, based on their outstanding wealth, this did not stop the brothers from adopting many of the domains of grandeur for themselves. Fritz Thyssen, according to Derix, even spent his time in the early 1900s importing horses from England, introducing English fox hunting to Germany and owning a pack of staghounds. He also had his servant quarters built lower down from his own in his new country seat, specifically to signal class distinction.

These are indeed remarkable new revelations showing that the traditional image put out by the Thyssen organisation of bad cop German, ‘temporarily’ fascist industrialist Fritz Thyssen, good cop Hungarian ‘nobleman’ Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza is even more misleading than we always thought.

****************

Truly lamentable are Derix’s attempts to portray Fritz Thyssen as a devout, christian peacenik and centrist party member. And so are her lengthy contortions in presenting Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza as the perfectly assimilated Hungarian country squire. She does, however, report that Heinrich’s wife had stated he did not speak a word of the language, which does not stop Felix de Taillez in volume 6 writing that he did speak Hungarian. ‘If you can’t beat them, confuse them’ was Heini Thyssen’s motto. Clearly, it has also become the motto of these Thyssen-financed academics.

Meanwhile, Derix’s book is the first work supported by the Thyssen organisation to confirm that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza did retain his German (then Prussian) citizenship. She also does venture to state that his adoption of the Hungarian nationality ‘might’ have been ‘strategic’. But these gems of truthfulness are swamped under the fountains of her gushing propaganda designed to make the second generation Thyssens look better than they were. This includes her development of August Junior’s role from black sheep of the family to committed businessman.

On the other hand, the author still fails to explain any business-related details on the much more important Heinrich Thyssen’s life in England at the turn of the century (cues: banking and diplomacy). How exactly did the family come to be closely acquainted with the likes of Henry Mowbray Howard (British liaison officer at the French Naval Ministry) or Guy L’Estrange Ewen (special envoy to the British royals)? A huge chance of genuine transparency was wasted here.

Derix also fails to draw attention to the fact that the August Thyssen and Josef Thyssen branches of the family developed in very different ways. August’s heirs exploited, left and betrayed Germany and were decidedly ‘nouveau riche’, except for Heinrich’s son Heini Thyssen-Bornemisza and his son Georg Thyssen, who really did involve themselves in the management of their companies.

By contrast, Josef’s heirs Hans and Julius Thyssen stayed in Germany (respectively were prepared to return there in the 1930s from Switzerland when foreign exchange restrictions came into force), paid their taxes, worked in the Thyssen Konzern before selling out in the 1940s, pooling their resources and adopting careers in the professions. Only the Josef Thyssen side of the family is listed in the German Manager Magazine Rich List; but for unexplained reasons Derix leaves these truly ‘working rich’ Thyssens largely unmentioned in her book.

****************

Fortunately, Derix does not concentrate all her efforts in creative fiction and plagiarisation, but manages to provide at least some substantive politico-economic facts as well. So she reveals that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza was a member of the supervisory board of the United Steelworks of Düsseldorf until 1933, i.e. until after Adolf Hitler’s assumption of power. This, combined with her statement that ‘Heinrich seems to have orientated himself towards Berlin on a permanent basis as early as 1927/8 (from Scheveningen in The Netherlands)’ pokes a hole in one of the major Thyssen convenience legends, that of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza having had his main residence in neutral Switzerland from 1932 onwards (i.e. conveniently from before Hitler’ assumption of power; having ‘left Germany just in time’); though this does not stop Derix from subsequently repeating that fallacy just the same (- ‘If you can’t beat them, confuse them’-).

Fact is that, despite buying Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland in 1932, Heinrich Thyssen continued to spend the largest amounts of his time living a hotel life in a permanent suite in Berlin and elsewhere and also kept a main residence in Holland (where Heini Thyssen grew up almost alone, except for the staff). His Ticino lawyer Roberto van Aken had to remind him in 1936 that he still had not applied for permanent residency in Switzerland. It was not until November 1937 that Heinrich Thyssen and his wife Gunhilde received their Swiss foreigner passes (see ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, page 116).

Derix also readjusts the old Thyssen myth that Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza went their separate ways in business as soon as they inherited from their father, who died in 1926. We always said that the two brothers remained strongly interlinked until well into the second half of the 20th century. And hey presto, here we have Simone Derix alleging now that ‘historians so far have always assumed that the separation had been concluded by 1936’. She adds ‘despite all attempts at separating the shares of Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, the fortunes of Fritz and Heinrich remained interlocked (regulated contractually) well into the time after the second world war’.

But it is her next sentence that most infuriates: ‘Obviously it was very difficult for outsiders to recognise this connection’. The truth of the matter is that the situation was opaque because the Thyssens and their organisation went to extraordinary lengths and did everything in their power to obfuscate matters, particularly as it meant hiding Fritz Thyssen’s and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s joint involvement in supporting the Nazi regime.

****************

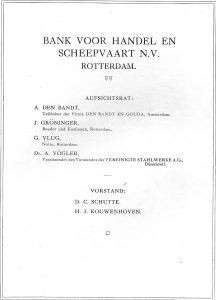

Amongst the Thyssens’ many advisors, the author introduces Dutchman Hendrik J Kouwenhoven as the main connecting link between the brothers, who ‘opened up opportunities and thought up financial instruments’. He worked from 1914 at the family’s Handels en Transport Maatschappij Vulcaan and then at their Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart (BVHS) in Rotterdam from its official inception in 1918 to his sacking by Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza during the second world war.

The asset management or trust company of BVHS was called Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor (RTK), which Derix describes as ‘repository for the finance capital of the Thyssen enterprises, as well as for the Thyssens’ private funds’. She does not say when it was created. ‘Its offices and all the important papers that Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza had lodged (at RTK) were all destroyed in a German aerial bombardment of Rotterdam on 14.05.1940’, according to Derix. To us this sounds like a highly suspicious piece of information.

Of the files of BVHS she curtly says that ‘a complete set of source materials is not available’. How convenient, especially since no-one outside the Thyssen organisation will ever be able to verify this claim truly independently; or at least until the protective mantle of Professor Manfred Rasch, head of the ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archive, retires.

Derix alludes to ‘the early internationalisation of the Thyssen Konzern from 1900’, ascribing her knowledge of its bases in raw material purchases and the implementation of a Thyssen-owned trading and transport network to Jörg Lesczenski, who published two years after us (and whose work, like that of Derix herself, was backed by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation). But she leaves cross-references aside concerning the first tax havens (including that of The Netherlands) which were set up in the outgoing 19th century, conveniently referring this area to ‘research that should be carried out in the future’.

Derix names the 1906 Transportkontor Vulkan GmbH Duisburg-Hamborn with its Rotterdam branch (see above) and the 1913 Deutsch-Überseeische Handelsgesellschaft der Thyssenschen Werke mbH of Buenos Aires (by the way: to this day ThyssenKrupp AG is a major trader in raw materials). She also states that American loans to the Thyssen Konzern started in 1919 via the ‘Vulcaan Coal Company’ (failing to mention that this company was based in London).

****************

According to Derix, August Thyssen began transferring his shares in the Thyssen companies to his sons Fritz and Heinrich in 1919, first those of Thyssen & Co. and from 1921 onwards those of the August Thyssen smelting works. She then adds that existing Thyssen institutions outside of Germany were used in order to carry out this transfer.

From 1920 onwards, Fritz Thyssen began to buy real estate in Argentina. Meanwhile, the Thyssens’ Union Banking Corporation (UBC), founded in 1924 in the Harriman Building on New York’s Broadway, is described solely in the language of the ‘transnational dimension of the Thyssens’ financial network’ and as being ‘the American branch of the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart’.

We had already detailed in our book how Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, via Hendrik Kouwenhoven, set up in Switzerland the Kaszony Family Foundation in 1926 to lodge his inherited participations and the Rohoncz Collection Foundation in 1931 to place art works he bought as easily movable capital investments from 1928 onwards. Now Derix writes that the Rohoncz Foundation too was founded in 1926. This is astonishing, since it means that this entity was set up a whole two years prior to Heinrich Thyssen buying the first painting to find its way into what he called the ‘Rohoncz Castle Collection’ (despite the fact that none of the pictures ever went anywhere near his Hungarian, then Austrian castle, in which he had stopped living in 1919).

The timing of the creation of this offshore instrument just proves how contrived Heinrich’s reinvention as a ‘fine art connaisseur and collector’ really was.

Derix even freely admits that these Thyssen family foundations were ‘antagonists of states and governments’. However, just like Johannes Gramlich in volume 3 (‘The Thyssens as Art Collectors’), she too leaves the logistics of the transfer of some 500 paintings by Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza into Switzerland in the 1930s completely unmentioned, including the fact that this represented a method of massive capital flight out of Germany. The associated topics of tax evasion and tax avoidance stay completely off her academic radar; ignoring our documented proof.

****************

In another bold rewriting of official Thyssen history the author states that the Thyssen brothers frequently acted in parallel in their financial affairs. And so it was that the Pelzer Foundation and Faminta AG came to be created , by Kouwenhoven, in Switzerland, on behalf of Fritz Thyssen and his immediate family. (Derix is hazy about exact dates. We published: 1929 for Faminta AG and the late 1930s for the Pelzer Foundation).

Derix points out that these two instruments also allowed secret transactions between the Thyssen brothers. She adds enigmatically that ‘Faminta protected the foreign assets of the August Thyssen smelting works from a possible confiscation by the German authorities’, whilst withholding any reference to a time scale of when such a confiscation might have been on the cards (is she suggesting a possibility prior to Fritz Thyssen’s flight in September 1939, i.e. anytime during the period 1929-1939?).

At the same time, in the 1920s, Fritz and Amelie Thyssen established a firm base in the south of the German Reich, namely in Bavaria – far away from the Thyssen heartland of the Ruhr – which Derix brands as a fact which has ‘so far been almost completely ignored by historians’. Of course, not only was this most royalist of German states close to Switzerland, but it was also, at that time, the cradle of the Nazi movement. Adolf Hitler also much preferred Munich to Berlin.

All the family’s financial instruments, meanwhile, continued to be administrated by Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor in The Netherlands. ‘These new Thyssen banks, companies, holdings and foundations created since the 1920s were connected to the Thyssen industrial enterprises (in Germany) through participations’, Derix continues.

These enterprises etc. were also supportive of the rising Nazi movement of course, such as when their Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart around 1930 demonstrably made a loan of some 350,000 RM to the Nazi party, at a time when both Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza had controlling interests in BVHS.

According to Derix, it was starting in 1930 that Heinrich Thyssen sold his shares in the United Steelworks to Fritz while Fritz sold his Dutch participations to Heinrich and as a result Heinrich Thyssen alone was in control of the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart from 1936 onwards.

Specifically, it was a Thyssen entity called Holland-American Investment Corporation (HAIC) which facilitated Fritz Thyssen’s capital flight from Germany. According to Derix, ‘(in the autumn of 1933, the Pelzer Foundation acquired) shares in HAIC from Fritz and therefore his Dutch participations which were pooled therein. This was done in agreement with the German authorities who knew of HAIC. But in 1940, the Germans found out that there was a considerable discrepancy between the 1,5 million Reichsmark of Dutch participations held in HAIC as had been stated and the actual, true value, which turned out to be 100 to 130 million RM.’

This is staggering, as the modern day equivalent is many hundreds of millions of Euros!

Considering that Heinrich’s wife stated that he had taken some 200 million Swiss Francs of his assets into neutral countries, this would mean that, together, the Thyssen brothers possibly succeeded in extracting from Germany the cash equivalent of close to the complete monetary value of the Thyssen enterprises! This is not, however, a conclusion drawn by Simone Derix.

One begins to wonder what there was actually left to confiscate from Fritz Thyssen once he fled Germany at the onset of war in 1939. Derix admits that his flight happened not least because he preferred to complete his self-interested financial transactions from the safety of Switzerland, with the help of Heinrich Blass at Credit Suisse in Zurich.

Although we had managed to unearth several leads, we did not know that the real overall extent of the Thyssen brothers’ capital flight was quite this drastic. For Simone Derix to point this out on behalf of the Thyssen organisation is significant; even if she fails to draw any appropriate conclusions, as they would most likely be at odds with her blue-sky remit.

Truly, and in the words of the far more experienced Harald Wixforth no less: for these ‘mega-capitalist(s) (…) the profit of their enterprises (i.e. their own) always assumed far greater priority than the public’s welfare’.

Needless to say that we await Harald Wixforth’s and Boris Gehlen’s volumes on the Thyssen Bornemisza Group 1919-1932, respectively 1932-1947 with great interest.

****************

In this readjusted official light, Derix’s admission that Fritz and Amelie Thyssen’s ‘expropriation’ in late 1939 ‘did not directly result in any curtailment of their way of life’ no longer comes as any surprise.

The author also finally reveals for the first time official departure details of Fritz Thyssen’s daughter Anita, her husband Gabor and their son Federico Zichy to Argentina. Apparently they travelled from Genua, sailing on 17.02.1940 on board the ship Conte Grande, bound for Buenos Aires. In order to provide her with befitting financial support, shares in Faminta AG had been transferred to the Übersee-Trust of Vaduz shortly beforehand, of which Anita Zichy-Thyssen, a Hungarian national, was the sole beneficiary.

Derix then states that by April 1940, Fritz Thyssen ‘used his political knowledge on the German Reich and the German armaments industry as an asset that he could use in exchange for support for his personal wishes’. But what exactly were those wishes? The hubristically delusional Fritz obviously thought he could get rid of Hitler as easily as he had helped him get into power. For this, he was prepared to share German state secrets with French Foreign Minister Alexis Leger and Armament Minister Raoul Dautry in Paris. But for Derix, rather than being anything as contentious as active treason or an expression of power, his behaviour is nothing more than an ultra-rich man’s legitimate right to express his elevated lifestyle choices.

While all previous Thyssen biographers, apart from us, have purported that Fritz and Amelie Thyssen suffered tremendous ‘excrutiations’ during their time in concentration camps, Derix confirms our information that they spent most of their German captivity in the comfortable, private sanatorium of Dr Sinn in Berlin-Neubabelsberg. She writes that they were kept there ‘on Hitler’s personal orders’ and ‘on trust’, though Fritz and Heinrich’s personal friend Hermann Göring, during his post-war allied interrogations, stated that their privileged treatment had been down to his initiative. After Neubabelsberg, they were taken to different concentration camps, but Derix is now forced to admit that they enjoyed ‘a special status’ which is retraceable ‘for each and every location’. Which makes one wonder, why German historians previously felt the need to misrepresent these facts.

Derix’s list of Fritz Thyssen’s allied, post-war interrogations is particularly noteworthy. It illustrates the seriousness in which he was considered to have been guilty of (albeit blue collar) war crimes, which should have been punishable by incarceration:

In July 1945 he was taken to Schloss Kransberg near Bad Nauheim, namely to the so-called ‘US/UK Dustbin Centre for scientists and industrialists’. In August, he went on to Kornwestheim before being taken, in September, to the 7th Army Interrogation Center in Augsburg.

Derix also vagely asserts that Fritz Thyssen was interrogated at some point ‘in 1945’ by Robert Kempner, chief prosecutor of the Nuremberg trials.

Thyssen suffered a collapse and had to go into medical care. He was taken to the US prisoners’ camp of Seckenheim, then to Oberursel. His health deteriorated. From April to November 1946 he went through various hospitals and convalescent homes between Königstein (where he made a surprise recovery) and Oberursel. From November 1946 onwards, he was at the Nuremberg follow-up trials as a witness (one presumes in the cases of Alfried Krupp and Friedrich Flick amongst others), while receiving continuous hospital treatment in Fürth.

On 15.01.1947 Fritz Thyssen was released to join his wife Amelie in Bad Wiessee. This was followed by his German denazification proceedings in Königstein, where he and Amelie lived at the sanatorium of Dr Amelung. In that court, as befitting his insincere character, Fritz Thyssen described himself as penniless.

Meanwhile, according to Derix, Anita Zichy-Thyssen made contact with Edmund Stinnes, who lived in the US and his brother-in-law Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, a close collaborator of US-secret service chief Allen Dulles. In the spring of 1947, ‘hoping to facilitate exit permits for her parents to go to America’, she met former US-senator Burton K Wheeler in Argentina, who travelled to Germany in 1948 ‘in order to help Fritz Thyssen out of his denazification problems’. It is certainly an aspect of high-level influence which we documented even more intensively, but which, astonishingly, Johannes Bähr in volume 5 (‘Thyssen in the Adenauer Period’) of the series has totally rejected.

****************

Another Thyssen who should have had problems with his denazification, but didn’t, was Heinrich’s son Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza.

While his brother Heini Thyssen went to the German school in The Hague, Stephan had boarded at the Lyceum Alpinum in Zuoz, Switzerland, where most pupils were from German speaking Switzerland, The Netherlands and the German Reich, respectively were Germans living abroad. Consequently, the school ran three houses named ‘Teutonia’, ‘Orania’ and ‘Helvetia’. After studying chemistry in Zurich and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he became an assistant at a research laboratory of the Shell Petroleum Company in St Louis. He then wrote his dissertation at Budapest University and began working in natural resources deposit research.

Since 1932, whilst living in Hanover, Stephan worked for Seismos GmbH, a prospecting company founded in 1921 by Deutsch-Lux, Phoenix, Hoesch, Rheinstahl and Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks AG. Derix writes: ‘From 1927 Gelsenkirchener, which belonged to the United Steelworks founded in 1926, was the main shareholder, holding 50% of the shares. This means Seismos came under Fritz Thyssen’s part of the family inheritance. (…) In the 1920s, prospecting groups of Seismos worked for oil companies such as Royal Dutch Shell or Roxana Petroleum in Texas, Louisiana and Mexico, looking for Oil. (…) Its radius then extended to the Near East, South-Eastern Europe and England’.

In 1937, Seismos was bought for 1.5 million RM by Heinrich Thyssen and incorporated into his Thyssensche Gas- and Waterworks. During the war, according to Derix, the company was ‘involved in the exploitation of raw materials in the (Nazi) occupied territories (…) During their withdrawal from the Eastern Ukraine during the 1943 tank battle of Kursk they had to leave behind much equipment’.

So, of no little importance for a company which so far, in Thyssen-backed histories, had been portrayed, if at all, as being of little consequence.

And not for the secretive Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza either, whose son Heini Thyssen shortly after the war would get his Swiss lawyer Roberto van Aken to lie to the US visa application department thus: ‘From the advent of the Nazis’ rise to power, and particularly from 1938 onwards, Dr Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’s (…) corporations were directed with the definitive purpose of minimising the Nazi armament efforts’ (The Thyssen Art Macabre, page 207).

It is, if anything, in that same obfuscating spirit that Derix still conceals the fact that the Seismos company moved its headquarters from Hanover to the Harz mountains during the war, where the Nazis’ weapons of mass destruction program (V-rockets) would come to be based.

Derix reveals that Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza was a member of the Nazi Aircorps and confirms he was a contributing member of the SS. Nazi officials apparently declared Stephan Thyssen’s political stance to be ‘beyond all doubt’. But Derix cannot bring herself to even mention, let alone detail his additional involvement with another company, namely Maschinen- und Apparatebau AG (MABAG) of Nordhausen, also in the Harz.

We had already established that Stephan Thyssen had become chairman of the supervisory board of MABAG in the early years of the war. This company, in conjunction with IG Farben, ‘had built a vast network of caves and tunnels in the Kohnstein mountain near Nordhausen equipped with tanks and pumps (…). From Februar 1942, Armaments and Munitions Minister Albert Speer recommended all possible support for the development of rockets. This represented massively ambitious armaments manufacturing plans and a great deal more work for MABAG, who, under the control of the Wehrmacht, were now also producing turbo fuel pumps for V-rockets’ (The Thyssen Art Macabre, page 160).

We had speculated that Stephan’s position of chairman of MABAG must have been due to a major investment made by his father Heinrich. While Simone Derix entirely fails to address any aspects of this topic, the lawyer and historian Frank Baranowski has unearthed a highly important document and explains on his website:

‘In 1940, the Deutsche Petroleum Konzern, following a change in their management, divested itself of all its works which did not fit into their framework of petroleum and coal extraction, including MABAG. Deutsche Bank negotiated the transfer of the share capital of 1 million Reichsmark into various hands. The majority was acquired by the solicitor and notary Paul Langkopf of Hanover (590,000 RM), which was most likely done on the orders of a client who wished to remain anonymous. Smaller share parcels were held by the Deutsche Bank in Leipzig (158,000 RM) and in Nordhausen (14,000 RM) as well as by Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza in Hanover (50,000 RM). On 14.09.1940 MABAG elected its new supervisory board: Director Schirner, Paul Langkopf, Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza and the Leipzig bank director Gustav Köllmann. (MABAG came to see itself as a company entirely geared to the production of armaments, …..including grenades, grenade launchers …….and turbo pumps for the A4-rockets)’.

It just so happens that Paul Langkopf was a professional whose services had been engaged by various members of the Thyssen family over the years. It can be presumed with near certainty that the ‘anonymous’ shareholder was Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza. The secrecy of the transaction fits his style completely. And while Baranowski’s and our views on the use of forced labour by MABAG differ, his evidence is another indication towards the fact that Heinrich was definitely 100% pro-Nazi during the war, even while he was apparently retiring from the world, far away in his Swiss safehaven, pretending to have nothing to do with anything.

The great Simone Derix, meanwhile, prefers to concentrate on relatively trivial revelations such as the fact that Stephan’s mother Margit also lived in Switzerland with her second husband, the ‘germanophile’, ‘antisemitic’ Janos Wettstein von Westersheimb, who lost his job at the Hungarian embassy in Berne when the war turned in 1943. Apparently, she lobbied ‘for Stephan to be allowed out of Germany (after the war) via Heinrich Rothmund, who during the war had been responsible in large parts for the anti-Jewish asylum policies of Switzerland’.

****************

Finally Simone Derix covers two other important topics in her book – as did we, albeit to a different degree -; namely: 1.) The Thyssens’ pre-war London gold deposits and their fate during, respectively after the war and 2.) the removal of the Thyssens’ and Dutch royals’ share certificates from the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart in Rotterdam to the August Thyssen Bank in Berlin during the war, and their return to Rotterdam after the war, through an illegal act by a Dutch Military Mission, code named ‘Operation Juliana’. We will analyse the coverage of those topics more adequately in our reviews of Jan Schleusener’s, Harald Wixforth’s and Boris Gehlen’s forthcoming volumes.

In both matters, members and associates of the Thyssen family played questionable roles, using their high-level (diplomatic and other) positions, to help the Thyssens play off one host nation against another, in their pursuit of limitless personal advantage. Simone Derix only takes her critical analysis as far as to say that these interferences allowed smaller states such as The Netherlands or Switzerland to pressurise victorious powers of the second world war in order to safeguard their own national interests in the Thyssens’ fortune.

While our book has been called a possible ‘handbook for revolution’, Derix describes hers as ‘a model showing the way concerning the central, investigative strands for a history of the infrastructures of wealth’. She evokes the driving forces of ‘jealousy’ à la Ralf Dahrendorf, by the general public towards the super-rich, while ignoring the concept of ‘anger’ at their selfish sense of perennial legal immunity, as described by many such as Tom Wohlfahrt.

Simone Derix’s writing style is very clear and during her book presentation at the Historisches Kolleg in Munich, the suave voice of the specially engaged Bavarian Radio reader made the passages sound like high literature, marinated in integrity. However, this academic, who was introduced to the audience by Professor Margit Szöllösi-Janze as ‘elite researcher’, definitely arrogates to herself a greater authority in broadcasting historical judgements than she is currently entitled to.

At the subsequent podium conversation with the historian and journalist Dr Joachim Käppner of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Derix rejected the concepts of power and of guilt unequivocally on behalf of the Thyssen family. In doing so, however, she had to be coaxed by Käppner repeatedly to focus her extremely hesitant flow of answers, which gave every impression, nevertheless, of having been pre-agreed.

Let’s hope Simone Derix does not remain the only contributor of the series to formulate answers to these important questions – But with more honesty, hopefully, if not greater independence from the questionable role of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. |

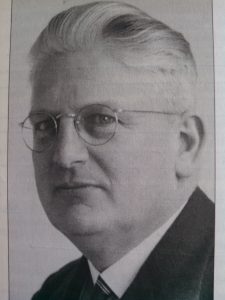

Fritz Thyssen and Hermann Göring in Essen, copyright Stiftung Ruhr Museum Essen, Fotoarchiv  Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza and Hermann Göring at the German Derby, 1936, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Batthyany-Clan, ca. 1930s, third from left Ivan Batthyany, husband of Margit Thyssen-Bornemisza, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Hendrik J. Kouwenhoven, general representative of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, copyright Stadsarchief Rotterdam  Three Thyssen brothers in harmony: from left Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, August Thyssen Junior, Fritz Thyssen, Villa Favorita, Lugano, September 1938, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield

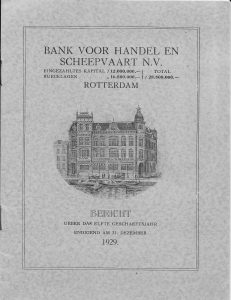

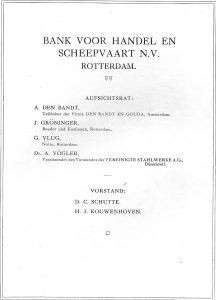

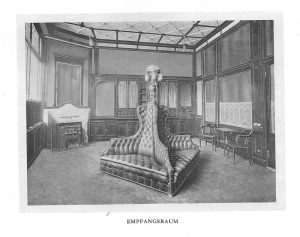

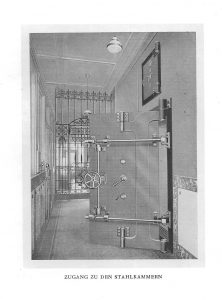

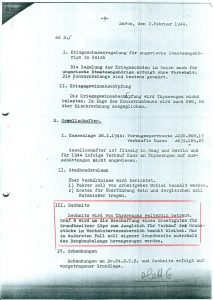

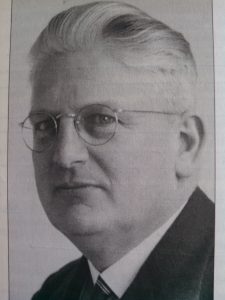

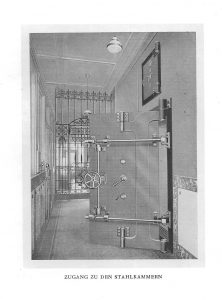

Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza with his wife Ingeborg, Hanover, ca. 1940s (Foto Alice Prestel-Hofmann, Hanover), copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, Year End Report 1929, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, Supervisory Board and Management Board 1929, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, Bank Counters, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, 1929, Reception Room, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield  Thyssen Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart Rotterdam, 1929, Steel Vaults, copyright Archive David R L Litchfield

|

|

Tags: "Operation Juliana", 7th Army Interrogation Centre, A4-rockets, Adolf Hitler, advisors, aerial bombardment, Albert Speer, Alexis Leger, Alfried Krupp, Allen Dulles, allied interrogations, allied investigators, Amelie Thyssen, American loans, anger, Anita Zichy-Thyssen, antagonists of states, anti-Jewish asylumc policies, antisemitic, Argentina, Armament Minister, art works, asset management, August Thyssen, August Thyssen Bank, August Thyssen smelting works, Bad Nauheim, Bad Wiessee, Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart, banking, Batthyany, Bavaria, Bavarian Radio, beneficiary, Berlin, Berne, Bismarck, Boris Gehlen, Bornemiszas, Bosch, Broadway, Budapest University, Buenos Aires, capital flight, capital investments, catholics, centrist party, class distinction, concentration camps, confisation, Conte Grande, contributing member of the SS, country seat, Credit Suisse, denazification problems, denazification proceedings, deposit research, Deutsch-Lux, Deutsch-Überseeische Handelsgesellschaft der Thyssenschen Werke mbH, Deutsche Bank, Deutsche Petroleum Konzern, diplomacy, Dr Amelung, Dr Joachim Käppner, Duisburg-Hamborn, Düsseldorf, Dustbin Centre for scientists and industrialists, Dutch Military Mission, Dutch participations, early internationalisation, Edmund Stinnes, England, envy, established aristocratic-bourgeois upper class, ethics, exploitation of raw materials, expropriation, Faminta AG, fascist, faux aristocracy, Federico Zichy, Felix de Taillez, finance capital, fine art, Forced Labour, Forced Labour at Thyssen, foreign assets of the August Thyssen smelting works, foreign exchane restrictions, fox hunting, Frank Baranowski, French Foreign Minister, French Naval Ministry, Friedrich Flick, Friedrich Thyssen, Fritz and Heinrich Thyssen - Two bourgeois lives in the public eye, Fritz Thyssen, Fritz Thyssen Foundation, Gelsenkirchener Bergwerks AG, Genoa, Georg Thyssen, Gerda Henkel Foundation, German armaments industry, German historians, German Manager Magazine, German state secrets, Germans living abroad, Germany, Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz, grenade launchers, grenades, Gustav Köllmann, Guy L'Estrange Ewen, Handels en Transport Maatschappij Vulcaan, Harald Wixforth, Harriman Building, Harz mountains, Heini Thyssen, Heinrich Blass, Heinrich Lübke, Heinrich Rothmund, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Helvetia, Hendrik J. Kouwenhoven, Henry Mowbray Howard, Hermann Göring, Historisches Kolleg, Hoesch, Hohenzollern, holdings, Holland American Investment Corporation, Hungarian citizen, Hungarian embassy, Hungarian nationality, IG Farben, Jan Schleusener, Janos Wettstein von Westersheimb, Johannes Bähr, Johannes Gramlich, Jörg Lesczenski, Josef Thyssen, Julius Thyssen, Kaszony Family Foundation, Kohnstein, Königstein, Kornwestheim, Krupp, Landsberg Castle, Leipzig, lifestyle, London, Louisiana, Lugano, Lyceum Alpinum, MABAG, Management, managers, Maschinen- und Apparatebau AG, Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Mausoleum, Mexico, morality, Mülheim-Kettwig, Munich, nation states, national socialism, natural resources, Nazi Aircorps, Nazi occupied territories, Nazi regime, Near East, Neubabelsberg, New York, Nordhausen, nouveau riche, Nuremberg Trials, Oberursel, offshore-Instrument, Orania, oustanding wealth, Paris, participations, Paul Langkopf, Pelzer Foundation, permanent residency, perpetrators, petroleum and coal extraction, Phoenix, plagiarisation, post-war interrogations, pre-war London gold deposits, production of armaments, Professor Manfred Rasch, Professor Margit Szöllösi-Janze, propaganda, public welfare, Quandt, Queen Wilhelmina, Ralf Dahrendorf, Raoul Dautry, raw material purchases, real estate in Argentina, refugees, Reichsmark, Rheinstahl, Robert Kempner, Roberto van Aken, Rohoncz Castle Collection, Rohoncz Collection Foundation, Rotterdam, Rotterdamsch Trustees Kantoor, Roxana Petroleum, Royal Dutch Shell, royalist, Ruhr, Sanatorium, Scheveningen, Schloss Kransberg, Second World War, secrecy, Seismos GmbH, Shell Petroleum Company, Siemens, Simone Derix, St. Louis, Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Swiss foreigner passes, Switzerland, tank battle of Kursk, tax avoidance, tax evasion, tax haven, taxes, Teutonia, Texas, The Hague, the Netherlands, The Thyssen Art Macabre, The Thyssens as Art Collectors, Thurn und Taxis, Thyssen & Co, Thyssen biographers, Thyssen Bornemisza Group, Thyssen enterprises, Thyssen Family, Thyssen family foundations, Thyssen fortune, Thyssen in the Adenauer Period, Thyssen Industrial History Foundation, Thyssen institutions outside of Germany, Thyssen Konzern, Thyssen-owned trading and transport network, ThyssenKonzern, ThyssenKrupp AG, ThyssenKrupp Konzern Archive, Thyssens' financial network, Thyssensche Gas- und Wasserwerke, Ticino, Tom Wohlfahrt, transnational lives, transparency, Transportkontor Vulkan GmbH, treason, trust company, turbo fuel pumps, Übersee-Trust Vaduz, ultra-rich, Union Banking Corporation, United Steelworks, US prisoners' camp of Seckenheim, US visa application department, US-secret service chief, US-senator Burton K. Wheeler, V-rockets, victims, Villa Favorita, Vulcaan Coal Company, war, war crimes, weapons, weapons of mass destruction, Wittelsbach, Zichy, Zuoz, Zurich

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Art, Thyssen Corporate, Thyssen Family Comments Off on Book Review: Thyssen in the 20th Century – Volume 4: ‘The Thyssens. Family and Fortune’, by Simone Derix, published by Schöningh Verlag, Germany, 2016

Thursday, August 17th, 2017

|

The Thyssens have always avoided revealing the details of their Nazi past, relying on a mixture of denial, obfuscation and bribery. But with the publication of our book ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’ in 2007 and revelations concerning the appalling Rechnitz massacre, this philosophy was becoming increasingly difficult to uphold. Finally they decided to recruit ten academics, via the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, to rewrite their personal, social, political and industrial past (a series called ‘Family – Enterprises – Public. Thyssen in the 20th Century’) in an attempt to burnish their reputation.

Sometimes this has been successful and sometimes not, as, despite their best laid plans, the books have often revealed more than the Thyssens might have liked, either directly or through the exposure of contradictions.

As the Thyssen-sponsored treatises have been published, we have reviewed each one in turn, in some considerable detail, and intend to do the same with their latest offering, ‘The Thyssens. Family and Fortune’ by Simone Derix. First, though, we want to examine the book’s one unique feature as, a whole decade after our revelations, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation has finally helped issue the first official Thyssen publication that contains a description of the dynasty’s involvement in Rechnitz life and in the ‘Rechnitz massacre’ of 24/25 March 1945 in particular – because this is a subject which we feel particularly passionate about.

Unfortunately, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation has chosen to allow Simone Derix to include the mere seven pages (of a 500-page book, derived from her habilitation thesis) in a manifesto that is as much a work of public relations on behalf of the Thyssens, as of Derix’s ambitious self-promotion within the ‘new’ field of ‘research into the wealthy’; the bottom line being that the Thyssens should be celebrated for their outstanding wealth, while they must be pitied for their victimisation at the hands of journalists, advisors, authorities, relatives, Bolshevists, National Socialists, etc., etc.

This makes Derix the kind of apologist of whom Ralph Giordano said that they will not tire of ‘turning victims into perpetrators and perpetrators into victims’. The fact that the Association of German Historians has seen fit to award Derix’s work the Carl-Erdmann-Prize (named after a genuine victim of Nazi persecution) is furthermore troubling.

* * *

Germany was a late developer in both its industrialisation and nationhood and emerged onto the international stage with an explosive energy that was to become catastrophic. While the extraordinarily hard-working, middle-class brothers August and Josef Thyssen created their family’s vast, late 19th century industrial fortune, August’s sons Fritz Thyssen and Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, influenced by their socially ambitious mother, turned their backs on bourgeois life and used their inherited wealth to ascend into a new-style, deeply reactionary landed gentry.

Derix describes how, in the early 20th century, far away from the original Thyssen base in the Ruhr, Fritz leased Rittergut Gleina near Naumburg/Saale, bought and sold Rittergut Götschendorf in Uckermark and bought Rittergut Neu Schlagsdorf near Schwerin, as well as Schloss Puchhof in Bavaria. Of course we already knew that Heinrich acquired, amongst others, the Landswerth horse racing stables near Vienna, the Erlenhof stud farm near Bad Homburg, with racing stables in Hoppegarten near Berlin, and the Rechnitz estate in Burgenland/Austria (formerly in Hungary).

Our research has shown that the brothers hunted at each other’s estates which discredits the spurious allegation repeated again and again by this academic series, including Derix, that Fritz and Heinrich Thyssen did not get on. A claim which is designed to obfuscate the synergies in the two men’s business dealings and particularly those benefitting the Nazi regime.

Both men adopted the behaviour of feudal overlords, enjoying the supplies of cheap and forced labour afforded their enterprises by the suppression of labour movements as well as armed international conflicts, which they fuelled with their factories’ weapons and munitions. The Thyssen brothers self-servingly meddled in politics, overtly (Fritz) or behind the scenes, through discrete diplomatic and society channels (Heinrich) – though the latter is denied vehemently by Derix and her academic associates.

Both Thyssen brothers helped bring about the eventual enthronement of the Nazis in 1933. Yet Simone Derix tries to reinvent them as the guiltlessly entrapped, illustrious captains of industry they never were in the first place.

By 1933 Heinrich’s daughter Margit (who had been born and had grown up at Rechnitz castle), corrupted by her ambitious father and anti-semitic mother, as well as her pseudo-pious Sacré Coeur education, had managed to elevate the family by marrying into Hungarian aristocracy (Ivan Batthyany) – as had Fritz Thyssen’s daughter Anita (Gabor Zichy).

On 8th April 1938, one week after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza gave his Rechnitz estate, which had once been in the Batthyany family for centuries from 1527 to 1871, to Margit, according to our research apparently so that he, ensconced in his Swiss hide-away on the shores of Lake Lugano, would not be seen to own any property in the German Reich.

Simone Derix alleges this was instead done for tax reasons.

All his Ruhr factories being owned by Dutch financial instruments, the Swiss authorities, who until the turning point of the war in 1943 were pro-German but whose ultimate stance was one of political neutrality, were satisfied that Heinrich would not become a political problem to them.

Through his company Thyssensche Gas- und Wasserwerke (later Thyssengas), Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza discreetly continued to fund both Rechnitz castle and the Batthyany matrimony. During WWII, the Walsum coal mine belonging to Thyssengas in the Ruhr used forced labour to the tune of two thirds of its labour force; a record in German industry. In the Rechnitz area, some mining interests were being exploited by the Thyssengas company.

* * *

For centuries the huge Rechnitz castle, in whose courtyard, it was said, an entire husars regiment could perform its drill, had been the power centre of Rechnitz. How exactly did this situation develop after the Nazis took charge of the country? Where in Rechnitz did the party and its organisations install themselves?

Simone Derix does not furnish any answers to these important questions, despite pretending to do so, by help of much verbose flourish. Instead, she writes in a vague, evasive manner: ‘The Batthyanys got along by mutual agreement (they found a consensual livelihood) at Rechnitz Castle during World War Two with representatives of the Nazi party and the Nazi regime’.

In 1934, 170 Jews lived in Rechnitz. On 1st November 1938, a week before Reichs Crystal Night, Rechnitz was declared ‘free of Jews’, a situation that members of the Thyssen family would have welcomed (see here). But Simone Derix pointedly refuses to acknowledge the anti-semitism of key Thyssens and instead reserves this characteristic for marginal characters.

In the spring of 1939, according to Derix, Hans-Joachim Oldenburg, whose father was a senior engineer at Thyssen and who himself had worked on agricultural estates owned by the Thyssen family, was sent to Rechnitz Castle to take charge of its estate management, which was soon relying on forced labourers from all over Nazi-occupied Europe.

That summer, Franz Podezin arrived in Rechnitz as a civil servant of the Gestapo border post. He had been an SA-member since 1931 and later became SS-Hauptscharführer. He also became the leader of the Nazi party in Rechnitz.

Simone Derix comments that „both posts of Podezin were in different locations“, but fails to pinpoint them. Stefan Klemp of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre has written that the Rechnitz Gestapo was headquartered in Rechnitz castle all along. Either his statement is correct or Derix is right when she alleges that Podezin only came to take up offices in the castle in the autum of 1944 when he became Nazi party head of subsection I of section VI (Rechnitz) of the South-East Earth Wall building works.

By avoiding clarity on these points, Derix fudges the issue and contributes to the vindication of culprits – particularly of the Thyssens as owners, funders and residents of the castle.

The activities on this reinforced defense system designed to hold up the Red Army were coordinated by the organisation Todt (run by Armaments Minister Albert Speer), by the Wehrmacht major-general Wilhelm Weiss and, in the section in question, by the Gauleiter of Styria, to which Burgenland then belonged, Sigfried Uiberreither.

Locals as well as forced labourers from different nations were employed, whose treatment depended on their position within the racial hierarchies proclaimed by Nazi ideology. Bottom of the heap and therefore having to endure the worst conditions and abuses, were Slavs, Russians and nationals of the states of the Soviet Union. But none of them were as badly treated as the Jews.

* * *

How exactly did Margit Batthyany-Thyssen spend these 12 years of Nazi tyranny?

The Countess took on the mantle of her grand-mother and mother as ‘Queen of Rechnitz’, while continuing to travel widely within the Reich. Having inherited her father’s interest in horses, she monitored Thyssen horse breeding and racing in Bad Homburg near Frankfurt, Hoppegarten/Berlin and Vienna, frequented races in various European cities and collected trophies on behalf of her father, who no longer wished to be seen to be leaving his Ticino safehaven.

In 1942, their Erlenhof stud Ticino won the Austrian Derby in Vienna-Friedenau and the German Derby in Hamburg. In 1944, their Erlenhof stud Nordlicht achieved the same feats, though the German Derby was held in Berlin that year due to the allied bombing damage on Hamburg.

At these public gatherings, Margit Batthyany mixed with and was feted by Nazi officials, who looked up to her as a member of the highest-level Nazi-state elite. It is clear that for her the war presented no change in her privileged lifestyle.

Each such event would have been a very public expression of support and legitimisation of the Nazi regime on behalf of the Thyssen and Batthyany families, but any reference to this function is absent from Derix’s treatise.

Margit also travelled regularly to Switzerland during the war, where she met her brother Heini and her father Heinrich in either Lugano, Zurich, Davos or Flims. They clearly sanctioned her life-style. Again, this is not mentioned by Derix.

During her war-time life in Rechnitz, Margit Batthyany apparently had affairs with both Hans Joachim Oldenburg (confirmed by the Batthyany family) and Franz Podezin (as stated by a castle staff member and mentioned by Simone Derix) – thereby confirming details relayed to us by Heini Thyssen’s Hungarian lawyer, Josi Groh, many years ago. Members of the Thyssens’ staff would have been in an ideal position to witness such things, as they cleaned rooms, served breakfast in bed or procured items of daily life of a private nature.

Strangely, Simone Derix still feels the need to proclaim such details as being mere „speculations“, thereby intimating that they are applied artificially to shed an undeservedly bad light on a Thyssen.

The only reason why we highlighted Margit Batthyany’s particular sexual penchant, was because it symbolises so powerfully the Thyssens’ intimate relationship with the Nazi regime, which will take on a particularly poignant dimension in terms of the post-war Aufarbeitung of the Rechnitz war crimes.

Academics such as Simone Derix and Walter Manoschek in particular, as well as members of the Refugius commemoration association have been at great pains to exclaim that we have somehow damaged the historiography of this chapter by „decontextualising“ it into a tabloid „sex & crime“ saga. The only thing that is achieved by these misguided accusations is that once again the Thyssens and Batthyanys are shielded from having to accept their responsibilities which they have so far, apart from Sacha Batthyany, shirked.

* * *

By 1944, the Nazi dream was turning sour. In March, the German army occupied Hungary and installed a Sondereinsatzkommando under Adolf Eichmann who organised the deportation of its 825,000 Jews. By July, some 320,000 had been exterminated in the gas chambers at Auschwitz concentration camp and ca. 60,000 became forced labourers in Austria. In October, when the Hungarian fascists took over from the authoritarian Miklos Horthy, the 200,000 Budapest Jews were targeted.

According to Eva Schwarzmayer, ca. 35,000 Hungarian Jews were used for wood and trench works on building the South-East Earth Wall. Of these up to 6,000 would come to work on the Rechnitz section and be housed in four different camps: the castle cellars and store rooms, the so-called Schweizermeierhof near Kreuzstadl, a baracks camp named ‘Woodland’ or ‘South’, and the former synagogue. Meanwhile, the Nazi Volkssturm (last ditch territorial army) had been constituted of which Hans Joachim Oldenburg became a member.

None of this is mentioned by Simone Derix.

In early 1945, with the Western and Soviet armies closing in on Hitler’s Germany, so-called ‘end-phase crimes’ were committed as part of the Nazi policy of ‘scorched earth’. This involved both getting rid of any incriminating evidence, including camp inmates, and to strike equally at any members of the home-grown population expressing doubts that Germany could still win the war.

This attitude lasted beyond Germany’s capitulation when witnesses willing to destify against Nazi war criminals were silenced through political, conspiratorial murders, as would happen repeatedly in Rechnitz.

Now began the so-called ‘death marches’ evacuating Nazi victims from their prisons ahead of the advancing Allies, only to see many of them die or be killed en route by members of the SA, SS, Volkssturm, Hitler Youth, local police forces etc. guarding them, in the open, under the eyes of the general public.

All in all, at least 800 Jews seem to have been killed in Rechnitz in this last phase of the war. The so-called ‘Rechnitz Massacre’ of some 180 Jews during the night of 24/25 March is in fact only one of several murderous events. Simone Derix mentions briefly that ‘shootings on the castle estate were already evidenced before 24 March 1945’, but she does not give any details of those other Rechnitz massacres.

Annemarie Vitzthum of Rechnitz gave evidence, during the 1946/8 People’s Court proceeding, that in February 1945 eight hundred Jews had arrived in Rechnitz on foot and that Franz Podezin ‘welcomed’ the exhausted people by trampling around on them on his horse.

According to Austrian investigators, 220 Hungarian Jews were shot in Rechnitz at the beginning of March.

Franz Cserer of Rechnitz stated that around mid-March eight sick Jews had been brought from Schachendorf to Rechnitz and that Franz Podezin shot them dead near the Jewish cemetery.

Josef Mandel of Rechnitz gave evidence that on 17 or 19 March a transport of 800 Jews arrived in Rechnitz from Bozsok (Poschendorf). The survivor Paul Szomogyi gave evidence that on 26 March, 400 Jews from his group of forced labourers had been killed in Rechnitz.

But not a single mention is made by Derix of the sheer scale of these additional crimes.

Eleonore Lappin-Eppel writes: ‘Paul Karl Szomogyi was transferred from Köszeg to the Rechnitz section on 22 or 23 March together with 3-5,000 co-prisoners’. Otto Ickowitz reported that sick prisoners from a group coming from the Bucsu camp were murdered in a wood near Rechnitz.

Unbelievably, Simone Derix deals with this accelerating horror by using the following technocratic language: ‘During the last months of the war very different types of camp communities with their own specific experiences collided and amalgamated with the local structure of domination’.

It almost sounds like a line from the pen of Adolf Eichmann himself.

* * *

On the night of 24/25 March 1945, the people involved in the massacre and/or the party seem to have included: the Nazi party leader of the Oberwart district Eduard Nicka and other functionaries from the same party HQ, various Styrian SA-men, Franz Podezin, his secretary Hildegard Stadler, Hans-Joachim Oldenburg, the SS-member Ludwig Groll, the leader of subsection II of section VI of the South-East Earth Wall building works Josef Muralter, Stefan Beigelböck, Johann Paal (Transport), Franz Ostermann (Transport) and Hermann Schwarz (Transport).

Derix adds: ‘The alleged perpetrators were recruited from the circle of this party society, which Margit and Ivan Batthyany also formed part of’.

Margit Batthyany would later help the two main alleged perpetrators, Podezin and Oldenburg, flee and avoid prosecution. If she had had nothing to do with the Rechnitz massacre and had found the actions reprehensible, it seems logical that she would have helped bring about the just punishment of the people involved rather than help them evade justice.

Simone Derix seems intent on absolving the Thyssens, even going as far as conjuring up the possibility that Margit might have helped victims – withouth, however, furnishing any evidence.

During the post-war proceedings Josef Muralter was said to have organised the ‘comradeship evening’ of 24 March 1945 at Rechnitz castle. Various academics have placed great emphasis on this fact in order to show that Margit Batthyany was not in fact the hostess of the event, as we had stated.

But as long as there are no documents forthcoming proving that any Nazi Party organisation paid for the festivities (and Derix does not furnish any), the fact remains that it was Margit Batthyany who was the overall hostess, as it was her family who paid for the castle and anything happening within its walls and grounds, for which documentary evidence is available (see here).

Simone Derix acknowledges the central role played by the conglomerate of people based at the Batthyany-Thyssen castle in the terrible abuses taking place in Rechnitz during WWII. She even acknowledges that some people might feel that there is room for directing questions of moral and legal responsibility at its owners. But she never implicates the Thyssens and Batthyanys in any responsibility or guilt and instead intimates that they probably did not ‘see anything’.

It is the same kind of defence as used by Albert Speer, when he lied to Hugh Trevor-Roper saying that he did not know about the programme of the final solution, because it was ‘so difficult to know this secret, even if you were in the government’. It is a tactic designed to shield powerful individuals and blame the general public.

As in previous volumes of this series, it is the Thyssen managers that get apportioned the full responsibility and in this case this falls on Hans-Joachim Oldenburg. He is said to have ‘extended his authority to exert power vis-a-vis his employers’, to have ‘taken an active part in producing a national socialist Volksgemeinschaft’ and to have ‘acted in a racist and anti-Semitic manner’, though Derix once again produces not a single piece of evidence to prove any of her allegations.

If Margit Batthyany had had a problem with this kind of behaviour, it would have been easy for her to leave the location and settle in any European hotel for the duration of the war. But she did not. So one must assume that she agreed with the racial and political victimisations that took place. Derix, however, fails to draw this obvious conclusion.

Margit chose to be part of the Rechnitz regime of terror. Derix chooses to use the less negative sounding description of “Volksgemeinschaft” instead.

Only when the Russians finally drew close to Rechnitz did Margit Batthyany, together with Hans Joachim Oldenburg and some of her staff, flee the scene in private cars, thereby leaving everyone else in the lurch; as did Franz Podezin.

Emmerich Cserer of Rechnitz said that on 28 and 29 March big transports of several hundreds of forced labourers left Rechnitz. Josef Muralter stated that he left the castle on 29 March with 400 castle cellar inmates.

* * *

The people of Rechnitz had to endure the final confrontation with the Red Army, the burning down as part of the Nazi scorched-earth policy of their central, 600-year-old castle, the post-war criminal justice investigations and the stigmatisation of the town that continues to this day. A stigmatisation which is not, however, due to the case having been ‘scandalised’ by media reports including ours, but which developed because, based on the deviousness of the escapees, the crime(s) could never be properly investigated and punished.

The people of Rechnitz did their duty by giving much evidence to judge the perpetrators. Nonetheless they were later accused by academics and some media outlets of maintaining a silence on the issue. When we went to Rechnitz as english-speaking outsiders, people talked to us unprompted and freely about the matter. Especially the town historian, Josef Hotwagner, who was recommended to us by townspeople as their spokesman. They did not hide what had happened in any way.

* * *

Having fled Rechnitz, Simone Derix explains, Margit Batthyany installed herself in April 1945 in a house in Düns in Vorarlberg/Austria. During the summer she went ‘travelling’. What Derix does not say is that Margit Batthyany entered Switzerland for the first time after the war, without any apparent difficulties in July 1945. It is inconceivable that Swiss authorities would not have been aware of what had happened in Burgenland only a few months earlier.

According to Derix, from November onwards Batthyany was working for the French military government in Feldkirch/Austria, in other words, she managed to access the western allies’ administrative set-up, likely because of her family’s overall high-level contacts and because she could offer intelligence on a region which was now under Soviet occupation. Derix, however, does not give any explanations for this sudden ‘assignment’.

A year later, in July 1946, Margit is said to have visited her brother Stephan Thyssen-Bornemisza in Hanover. This was a man who had been a financially contributing member of the SS and involved in various industrial activities using forced labour for the German war effort throughout WWII, though he subsequently flatly denied this. Derix does not mention Stephan Thyssen’s pro-Nazi activities at this stage.

According to Derix, Margit Batthyany, financially dependent on her father as she was, moved into his Villa Favorita in Lugano in August 1946.

Our research revealed that in November 1946, Margit wrote to her sister Gaby Bentinck: ‘So as not to be obvious, I have agreed with O.(ldenburg), that he will first of all go to South America on his own for two years. I am expecting to receive visa for him, what do you say?’. This evidence was provided by us to Sacha Batthyany and used in his newspaper article (but not his book!). But Simone Derix ignores it and writes simply that Margit had ‘plans, in November 1946, to leave Europe’.

The fact that Margit Batthyany could at this point in time envisage a transfer of assets between countries and even continents shows again how privileged her situation was in comparison to that of the vast majority. She could certainly also rely on investments that the family had already made in South America before the war.

Meanwhile, in Burgenland in 1946 eighteen people were accused of having committed war crimes in Rechnitz, seven of whom were indicted in a Peoples’ Court, including, in absentia, Franz Podezin and Hans Joachim Oldenburg. But only two would receive sentences, which were eventually quashed in early 1950s Austrian amnesties. The proceedings took two whole years and in fact were only finally closed 20 years later in 1965 in Germany.

On 7 January 1947 Margit Batthyany was questioned for the first and last time in the matter by the Swiss cantonal police in Buchs (Swiss State Security File, entry C.2.16505). She never had to appear as a witness at the Austrian court, a fact that has been denounced on the information plaques of the Rechnitz memorial unveiled in 2012 (in the smaller English and Hungarian version only, not, for some reason, in the main German version).

Was Margit Batthyany-Thyssen ever summoned to appear in court? If not, why not? Did the neutrality of her host country Switzerland play a role in this failure? Or was the protection afforded her simply down to her highly advantageous social position?

Simone Derix alleges that the Countess ‘tried’ to give Oldenburg an alibi during her questioning. In reality she did give him an alibi by saying that he had not left the party at any time of the night. Sacha Batthyany’s conclusion in both his article and his subsequent book is more forceful: ‘She protects him, her lover, because Oldenburg has been seen by witnesses at the massacre’.

In the summer of 1948, as per our research, Margit wrote another letter to her sister Gaby Bentinck: ‘O.(ldenburg) has a fantastic offer to go to Argentina and join the biggest dairy farm. He will be there by August’. This evidence was once again provided by us and published by Sacha Batthyany, but is not mentioned by Simone Derix, who also failed to consult certain family archives in London.

On 13 August 1948, the court noted that according to a verbal message from the constabulary in Oberwart, both Franz Podezin and Hans-Joachim Oldenburg were living in Switzerland and intended to emigrate with Margit Batthyany to South America, thereby following her husband, who had already gone there. On 30 August 1948, Interpol Vienna informed the Lugano authorities by telegram:

‘There is the danger that (Podezin and Oldenburg) will flee to South America. Please arrest them’. The arrest warrants against the two evaders were published in the Swiss Police Gazette of 30.08.48, page 1643, art. 16965. But no arrests took place. All this has been investigated and published by Sacha Batthyany. Simone Derix fails to mention it.

Eleonore Lappin-Eppel summarises the 1946/8 proceedings thus: ‘Because of the flight of the two alleged ringleaders Podezin and Oldenburg the court had considerable difficulties in establishing the truth’.

Sacha Batthyany comments: ‘(Margit) helped the alleged mass murderer (Oldenburg), flee’.

But the line taken by Simone Derix is once again one of protecting Margit Batthyany-Thyssen when she says: ‘It remained unclear what role Margit had played when two main perpetrators were able to avoid an interrogation by the Austrian authorities and thus a possible punishment.’

Simone Derix also alleges that Franz Podezin was questioned in the matter. But this is untrue. Podezin was never once questioned about his alleged involvement in the Rechnitz massacre.

Thus Derix is not only clearly engaged in practices of exoneration on behalf of the Thyssen family, her publication is also lagging ‘behind’ in terms of the stage of advancement of research on this subject, as well as grossly inaccurate on a crucial point.

* * *

Margit Batthyany-Thyssen and her husband Ivan Batthyany did come to live between 1948 and 1954 on a farm they had bought in Uruguay. What became of Podezin’s and Oldenburg’s travel plans is less clear.

Simone Derix explains that by 1950 Hans Joachim Oldenburg was working on the Obringhoven agricultural estate, which was owned by Thyssengas, a fact that has never before been revealed. It is a rare, valuable new contribution to the Rechnitz case made by Derix.

This shows that the Thyssen family was happy to continue employing this farm manager, who had been indicted for war crimes in an Austrian court. The Thyssens thus provided Hans Joachim Oldenburg not only with a livelihood but as well, it seems, with protection from further investigation.

Yet Derix fails to comment critically on this important issue.

As far as Franz Podezin is concerned, according to Stefan Klemp of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, he had gone underground as an agent for the Western allies in East Germany. Apparently, he was arrested in the Soviet zone of occupation because of his activities for allied intelligence services and condemned to 25 years in prison, but released after 11 years and sent to Western Germany, where he came to live as an insurance salesman in Kiel.

In 1958, the Central Office of the County Judicial Administrations for the Clearing up of Nazi Crimes was instituted in Ludwigsburg. In 1963, it filed murder investigation proceedings against Franz Podezin and Hans Joachim Oldenburg. A letter dated 18.02.1963 makes clear that the prosecutor was aware that Podezin was so heavily incriminated that he needed to be arrested, yet he delayed proceedings. Oldenburg was questioned by the Central Office in Dortmund on 26.03.1963.

When police eventually moved in to arrest Podezin on 10 May, he had fled to Denmark. Kurt Griese, an ex SS-Hauptscharführer and now governmental criminal investigator, further blocked proceedings according to Klemp, making it possible for Podezin to travel to Switzerland, where he blackmailed Margit Batthyany-Thyssen into facilitating his flight to South Africa. There he worked for Hytec, a company associated with Thyssen AG, as Stefan Klemp established.

Sacha Batthyany writes: ‘Did Aunt Margit, nee Thyssen, help (Podezin) flee in the sixties and then also procured him the job in South Africa?’. But the topic is ignored by Simone Derix.

As the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported in addition to our 2007 article, although one of the German investigators reported to the Austrian Justice Ministry in 1963 that Margit Batthyany was suspected of having aided the two Rechnitz murderers flee, charges were never pressed against her. Why not? Derix does not mention this and thus furnishes no explanations.

According to Eva Holpfer, the proceedings against Hans Joachim Oldenburg were closed on the orders of the prosecutor on 21.09.1965 due to a lack of evidence.

By the 1960s Margit Batthyany was back at the Austrian Derby in Vienna collecting trophies on behalf of the winner Settebello whom she had bred. She also regularly returned to Rechnitz (where she died in 1989), especially for the hunting season, spreading largesse in the form of plots of land and other gifts to locals, as relayed to us by Rechnitz people and confirmed by Sacha Batthyany.

In 1970 Margit Batthyany-Thyssen was accorded the Swiss citizenship papers she had tried to obtain ever since the end of the war. The same year Horst Littmann of the German War Graves Commission began digs in Rechnitz but had to stop because permission from the Austrian Ministry of the Interior was not forthcoming.

* * *

In the 1980s, the anti-fascist Hans Anthofer initiated the first Rechnitz memorial for the Jewish victims. But in the early 1990s the Jewish cemetery in Rechnitz was still being defaced and according to Eva Schwarzmayer even during the memorial year of 2005 people in public positions still said that it was unsure whether the Kreuzstadl massacre had really happened.

Then, in 2012, the Rechnitz memorial became extended into a museum, which was opened by the Austrian President Heinz Fischer who assured the listeners that ‘everything will still be undertaken to find the bodies of the victims’.

The Refugius commemorative association has spoken of a ‘change of attitude’ that has taken place in Rechnitz. At the same time, they disparage on one of the museum’s information panels that ‘the active remembrance and commemoration work still does not meet with a general popular consensus’.

What is noticeable is that, contrary to their avowed intentions of wanting to establish the truth and honour the victims (see footnote), none of the Thyssens have actually ever manifestly taken part in the annual commemorations of the Rechnitz massacre.

The Office of the Burgenland County Government has told us that ‘The Thyssen respectively Batthyany Family do not play any role whatsoever in the remembrance culture and Aufarbeitung of the past of that area or of Austria as a whole’.

Why do they not?

Sacha Batthyany has reported that he got threatened by members of his family because of his attempts to clarify their history during the Nazi era.

As far as the people of Rechnitz are concerned, they are understandably fragmented on the issue and it would be very odd were it otherwise.

But with the Thyssens there is no such fragmentation. They seem unitedly unapologetic and non-participating. This is now presumably reinforced by their belief that the academics they commissioned have come to the conclusion that they are blameless.

The truth, however, is that they are not blameless and it is now high time for the Thyssens to express clearly which side of the fascist / anti-fascist dividing line they stand on.

Only if the Thyssens (and the Batthyanys as their local ‘representatives’) assume their position as role models can the commemoration culture of the Rechnitz massacre become consensual for the rest of the population.

By attending the next commemorative event in Rechnitz in late March 2018 – and being reported in the media to have done so – members of the Thyssen dynasty can make a truly public statement in this regard and meet their historical responsibility transparently and effectively.

After all the prevarications of the past, the informed public now expects these families finally to do their fair share in the matter of the Rechnitz Massacre and show REAL solidarity in the honouring of the dead and maimed of those catastrophic events.

* * *

Footnote: The following statements were made in the past: