October 21st, 2009

| Four or five years ago, a member of the Thyssen family told me his brother Georg was selling off their manufacturing companies and concentrating on investment services. Apparently, he had already been getting a regular 10% return on family money when the best anyone else was getting was 5 or 6%.

Well, it appears Georg was probably getting as much as 15 or 16% and taking the margin as profit. It was obviously good business. So good that he managed to sell the deal to others. So far, so good. But then the source of his miraculous return ceased to be so miraculous, as Bernie Madoff’s dark little secret became very, very public.

Quite rapidly those who had used the services of the Thyssen-Bornemisza company ‘Thybo Advisory’ realised that the chances of getting their money back from Bernie were non-existent, especially when he was awarded a 150-year jail sentence, so they (US-Trustee Irving Picard and the Belgian Investor Representative Deminor) decided to take Thybo Advisory to court. Judging by the fact that Thybo’s secretive Monaco offices were recently the subject of a police raid, one has to assume there may have been a certain lack of transparency somewhere down the line.

This is obviously bad news for the Thyssens, and all those who invested in Thybo. It appears that the amount lost may have been a great deal more than originally thought. The Monegasque authorities are also particularly allergic to these kind of goings on and may soon be asking the family to relocate. Perhaps the Thyssens will join many others in learning that the reluctance to pay tax and the desire to make a profit without working inevitably ends in tears. |

The Monaco headquarters of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Group and Thybo Advisory on Boulevard Princesse Charlotte |

Tags: Bernie Madoff, Georg Thyssen-Bornemisza, Monaco, Thybo Advisory, Thyssen Bornemisza Group, Thyssen Family, Thyssen-Bornemisza

October 5th, 2009

Tags: Bronzino, Thyssen-Bornemisza

September 2nd, 2009

| “Readers of my book should be all too aware of my questioning of the authenticity of many of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection’s claimed master pieces, but only now, finally, has a major art historian supported my claim by insisting that the ‘Dürer’ ‘Jesus Among the Scribes’ in the Madrid Museo Thyssen is a fake”.

http://www.nnonline.de/artikel.aspart=1079333&kat=48&man=3

Translation by Caroline Schmitz of the article by Birgit Ruf in the Nürnberger Nachrichten of 02.09.2009.

”Dürer would have been ashamed of this work”

Nürnberg art historian raises doubts concerning the authenticity of a Dürer painting

Thomas Schauerte, the new head of the Nürnberg Albrecht-Dürer-House and an expert on the work of the famous artist has dared to proclaim an explosive theory. He is convinced that the painting ‘Christ Among the Scribes’, a main attraction in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, is not by Albrecht Dürer’s hand.

Thomas Schauerte had his first doubts concerning the authenticity of the painting – which was allegedly painted by Dürer in 1506 on poplar wood – in 2003 when he visited the big Dürer retrospective at the Albertina in Vienna. As a long-standing researcher on Dürer, who wrote his dissertation on the artist and participated in the publication of the full catalogue of his prints, Schauerte viewed the Albertina exhibition through the eyes of an expert. There, for the first time in many years, the famous painting was shown together with five existing drawings, showing details of the overall composition. It is a representation of the 12-year-old Christ in discussion with the scribes inside the Temple.

Crass decline in quality

“When one compares the Dürer drawings directly with the painting, one can see a crass decline in quality”, says Schauerte. Compared to the brilliant drawings the painting, he says, is “simply bad”. Clear words, which the art historian backs up by demonstrating various inconsistencies. “The head of Christ was originally planned in much too small a size”, he says and, using a reproduction of the painting, points towards a “shadowy area” where the head was subsequently “increased in size” through the addition of more hair.

And in Schauerte’s opinion another mistake, namely on the scribe positioned on the very left, would “never have been made” by the great master: the noble elder is possibly 70 or 80 years old, but he has the hands of a young man – no wrinkles, no age spots, no veins can be seen. “But Dürer above all people required in his teachings that a figure has to be harmonious and that the details must all fit together”, says Schauerte.

A mix of references

Apart from these details, he has some things to criticise concerning the overall composition as well. He says that the heads have simply been cut off at the upper edge of the painting, that the people in the work do not get into any kind of relationship with each other through visual contact and that no coherent image space is being created. Based on all these observations, Schauerte concludes: The painting is a product in the style of Dürer from the early 17th century, a pastiche, a mix of references. At the time there was a veritable Dürer-boom, so that everything that came from the master sold mit reißerischem Absatz. Therefore, those were also good times for Dürer-copyists and falsifiers.

If you listen to the 42-year old, you wonder very quickly why nobody else before him noticed the inconsistencies. As Thomas Eser, head of the Dürer-Research-Centre at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, confirms, no other scientist has ever raised doubts as to the authenticity of the Madrid painting, which surfaced for the first time in 1642 in a private collection in Rome and was sold to the Thyssen Collection in 1934. “The painting is not documented anywhere before 1642. That is unusual for Dürer”, states Schauerte, who recently moved from Trier University to the Dürer House in Nürnberg. When the painting was sold around 1930, “the critical awareness was not yet so much in existence”. And that people in Madrid “are not very keen to open this box” is something one can comprehend.

Only in private collections

Eser explains: “Since the painting was known, there was a consensus amongst Dürer researchers that it is a Dürer. But as it only used to hang in private collections and not in world museums, it “hasn’t been critically examined often enough until now”. Eser welcomes the fact that his research-colleague Schauerte has now done so: “He adds to the knowledge by suggesting alternative viewpoints”. Schauerte’s “heretical theory”, which he has worked six years to back up, will now be published in time for the Book Fair in the series “Dürer-Research” by GNM-Verlag (German National Museum Publishers).

“The painting has no coherent spatial-narrative composition, but is, rather, a juxtaposition of Dürer-heads at close quarter”, Eser agrees with Schauerte’s observations. The latter asserts in his essay that almost all the heads of the scribes in this painting have models in other works by Dürer, but that most of them appear after the year 1506, which is the year inscribed on the tableau, next to the AD-monogram.

Like a medley

Eser draws a very graphic comparison: “If it were a pop song, one would say it is a medley. There are many Dürer themes placed in it, but only a few bars of each of them”. Eser thinks that Dürer himself would have made higher demands as to the “coherence of the description of space.” Schauerte expresses it even more drastically and insolently: “Dürer would have been ashamed of this work”.

Speaking of ashamed: That’s what the Thyssen Collection might prove to be if Schauerte is right. He has not yet spoken to the people in charge in Madrid about his “radical theory”. The Nürnberg researcher knows: “If I’m right, it would be a catastrophe for the collection”. The painting would then only be worth a fraction of its original worth. But Schauerte has also been in this business long enough to know: “It’s a very long process for new research results to become acknowledged”.

http://www.nz-online.de/artikel.asp?art=1080338&kat=49 |

Art historian Thomas Schauerte, Director of the Albrecht Dürer Haus in Nürnberg (photo: Karlheinz Daut, Nürnberger Nachrichten)  'Jesus Among the Scribes', attributed by the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid to Albrecht Dürer, but claimed by Thomas Schauerte to be the work of an early 17th century copyist. |

Tags: Albertina Wien, Albrecht Dürer, Albrecht Dürer Haus, Dürer-Forschungsstelle, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Jesus Among the Doctors, Jesus unter den Schriftgelehrten, Museo Thyssen, Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Nürnberg, Nürnberger Nachrichten, Thomas Eser, Thomas Schauerte, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

July 14th, 2009

| I recently came across an article about August Thyssen in the summer series on famous scions of the Lower Rhine region, published by the Rheinische Post newspaper, under the promising headline ‘A Globaliser From The Start’. But it contained the sentence ‘After the World War, August Thyssen lost his foreign participations’. As somebody who has studied the Thyssens for some fourteen years now, it was the kind of throw-away remark that sharply reminded me once again of the systematic manipulation of history that has accompanied this dynasty’s personal and corporate affairs for a very long time.

If you wish to get a very basic idea of what I’m talking about, go to German Wikipedia and check out the entries for Alfred Krupp, Hugo Stinnes, Friedrich Flick and August Thyssen; all four legendary German industrialists of similar status and place in history. Krupp warrants 5 illustrated pages, Stinnes 11, Flick 10, but Thyssen barely manages to make three quarters of a page! Why should this be so? The chief publicist and archivist of ThyssenKrupp, Professor Manfred Rasch, is more than capable of producing lengthy features on the founder of the Thyssen empire at opportune moments in local publications, such as Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, which are hugely sympathetic to the image of a company that still remains one of the major employers in the Ruhr area, as well as far beyond. So why does he not ensure that extensive and accurate information is available on a more general level?

The answer is: because there are many black holes in this dynasty’s history which would be too difficult to broach. Instead, gloss-overs and simplifications have been produced over the years by the official guardians of the Thyssen legacy and reproduced by unwitting journalists and historians. But even the most consistently spin-doctored histories are eventually bound to come unravelled. This is particularly true in times of bust such as today, when money becomes scarce and people re-examine their loyalties; as long, of course, as they can enjoy the freedom of democracy rather than being forced into the shackles of authoritarian rule so admired by the likes of Ecclestone, Mosley & Co.

One reason why the Thyssens have always purported to have ‘lost everything’ in the war (for the family members tend to ‘go the extra mile’, insisting all was lost, not just the foreign assets) is to excuse their involvement in arming the German Empires of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Adolf Hitler respectively. If it were shown that they actually profited from those regimes, the Thyssens would receive far less sympathy and respect than they do when portrayed as the sacrificial victims of the conflicts, who had to rebuild their fortunes each time from scratch by the sweat of their own brows. The latter being very much the picture painted on the new website of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

In actual fact, while other industrialists were punished for their support of the Reich, the Thyssens were not. They were even compensated for their losses. After World War I, this included their Lorraine ore mines and steel works, which the French insisted they give up. Heini Thyssen himself admitted to David and myself that far from his family losing, for instance, his grand-father’s Brazilian interests after 1918, he was able to liquidate some of them in the 1970s at vast profit. Despite such good fortune, ‘foreign assets’ have always been a particularly contentious issue in the Thyssen historiography, not least because this most quintessential of German dynasties, whose name still remains one of those inextricably linked with the fatherland’s deepest sense of national prosperity, honour and pride, has continuously reaped the benefits of German industry, while simultaneously refusing to admit allegiance to the country.

While the destruction of August Thyssen’s personal files after his death in 1926 ensured the public could never realise that this supposed German patriot had in fact moved his ultimate ownership structures abroad before 1914, a more overt public relations exercise was necessary after 1945 when the magnitude of the Nazis’ criminal activity came to light. That is why official communiques began to over-engineer Heinrich Thyssen’s cosmopolitan credentials, giving assurances that he ‘had distanced himself from Germany as a young man’, that he ‘became a Hungarian in 1906’, that he ‘gained a doctorate in philosophy in London’ and that he ‘settled in Switzerland in 1932’. On closer inspection even of the official sites, however, inconsistencies soon start to appear for all of these claims.

As far as Heinrich’s nationality is concerned, ThyssenKrupp AG has for some time now resorted to the line: ‘He kept his Hungarian citizenship until he died, but nevertheless acted ‘deutsch-nationally’ at times in the 1920s and 1930s. For this vague statement to be allowed to paraphrase the activities of such an important (if shielded) figure of 20th century history is quite simply astonishing. And of course it can in no way explain how German works owned by Heinrich Thyssen were still able to claim war damages from the allied government for Germany in 1946 on the basis of Heinrich being ‘a German abroad’. The fact is: Heinrich Thyssen lived in Lugano from 1938 (not 1932! – more of this later) until his death in 1947, controlling his German interests with the help of visiting managers and this makes him somebody who acted ‘deutsch-nationally’ (if this is what you want to call it), throughout Hitler’s time in power and beyond.

Turning to Heinrich’s academic title: the assertion of a doctorate in philosophy gained in London is pure fabrication. That is why it does not appear on the German websites, where it is clear and very acceptable to people that the doctorate was gained in Germany in the field of natural sciences. It is, on the other hand, very much emphasised in Spain, where the government’s expenditure of in excess of $600 million dollars on the Thyssen-Bornemisza art collection seems to make it imperative to stress the founder’s alleged cultural and specifically non-German credentials.

Here on www.museothyssen.org, we also find echoes of Francesca Habsburg‘s recent attempts to designate August Thyssen as the true founder of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection (even to the extent where a recent museum web-incarnation called him ‘August Thyssen-Bornemisza’!), thereby rebranding the whole dynasty as the art collectors she would like them to be (making her fourth in a row) rather than the industrialists and bankers that they really were. But the official website of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum also makes another announcement: ‘We know the collection was installed at Rohoncz Castle before Heinrich abandoned Hungary in 1919’. This is particularly worrying as the comprehensive catalogue of the museum squarely confirms the documentation in the Thyssen Archives showing that the first purchase made for the collection was in 1928 (unless that too has now been re-written!)

The smoke and mirrors at Museo Thyssen continue: ‘It is through the correspondence between August Thyssen and Auguste Rodin, namely in a letter from 1911, that we can see that August’s son Heinrich had by that time started his collection’. We have researched the same letters during the writing of our book but never came across anything that would confirm this. The official line basically intimates that with his transformation into a ‘Hungarian aristocrat’ in 1905 (the real dated being 1906-07), Heinrich Thyssen had also, somehow, acquired an art collection.

What seems clear to me is that people in charge of that museum are finally realising that they have a particularly grave problem on their hands. However, not knowing what to do about it, their inability to address serious issues breeds insecurity and confusion. That’s why another sentence has been added to the website: ‘We have few details about the first years of the collection’. While I guess it would be unfairly over-stressing the point if one reminded the Spanish tax payer once again, how much money he contributed and is still paying to the Thyssen Museum, the indelible facts concerning the early history of the collection are these: the Thyssen Collection was never at Rohoncz (Rechnitz). It was only named ‘Rohoncz Collection’ by Heinrich Thyssen with the specific aim of making it sound like an Austro-Hungarian heirloom. Unbelievably, the public as well as the media have bought this fiction decade after decade.

The staff of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung got equally confused in October 2007, when they ran David’s piece on Heinrich Thyssen’s daughter, Margit Batthyany, and her involvement in the murder of 180 Hungarian Jews at Rechnitz Castle in March 1945, which had been published two weeks earlier in The Independent. None of the many continental journalists and historians who subsequently busied themselves in denigrating our work, such as Anja Seeliger of Perlentaucher fame for instance, actually figured out that the reason why the two features were markedly different was not only because of overt censorship in Germany, but also because staff at FAZ saw fit to fact-check the article – the fruit of 14 years of research – against the grossly inaccurate (ThyssenKrupp AG / Museo Thyssen / Thyssen Family) Gospel According to Wikipedia, the same Wikipedia that has rejected our corrective suggestions outright.

Back at Frankfurter Allgemeine: out came 1938 as Heinrich’s settlement date in Switzerland, in went 1932 (to ensure that Heinrich’s presence in Germany after Hitler’s ascension to power could be denied). Out went the proviso that the collection was never at Rohoncz, in went the age-old phrase that it was housed there. Out came our statement that the Thyssens acquired the Erlenhof stud farm from the liquidators of the persecuted Jew, Moritz James Oppenheimer, in 1933. In went the fabrication that Heinrich Thyssen’s business empire was completely separate from August or Fritz Thyssen’s empire. While we are grateful to FAZ for publishing the feature, this type of inaccurate ‘editing’ of copy in a newspaper of such quality should be of concern to everyone.

And even today, two years after the publication of our book, the Spanish museum continues to insist that ‘Heinrich Thyssen’s enterprises were completely separate from the German steel industry’, when even ThyssenKrupp’s website has been admitting for a while now that Heinrich owned the Press- and Rolling Works Reisholz and the Oberbilker Steelworks, both plants that produced canon for Adolf.

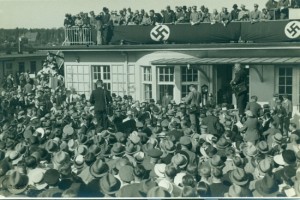

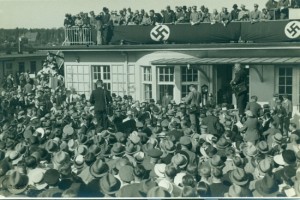

Spain is also still holding on to the idea that Heinrich was ensconced in Switzerland from 1932 onwards, where he ‘opened the doors of his gallery to the public in 1936’. Apart from family archival evidence, Heinrich’s own war-time curator, butler and companion, Sandor Berkes, assured us that the gallery building remained unfinished until 1940 and was only opened to the public in 1948. As can be seen from the picture above, far from being locked away in his Swiss villa, in 1936 Heinrich was, amongst other things, happily socialising at the German Derby with his personal friend Hermann Göring, whom he also assisted with personal and Reich banking facilities.

With a background of such systematic disinformation, it does not come as a surprise that the personal assertions by Thyssen family members are also becoming more and more ‘retrograde’. Francesca Thyssen is quoted as explaining to the Austrian ‘News’ Magazine in November 2008 (available in hard copy version only, not online!): ‘Of course my great-uncle (Fritz) was truly deeply enmeshed in Nazi-crimes, that’s no secret. That’s why my grandfather (Heinrich) took the name Bornemisza from his wife, because he left this whole family. Because he wanted to be different and wanted to leave this family’. Or, in other words: Heinrich Thyssen foresaw the coming of the Third Reich by 27 years!…

I can understand that the various guardians of the Thyssen legacy would feel the need to rewrite the unacceptable history of this family. But I do not appreciate the fact that journalists, historians and those who should know better continue to encourage the belief in facts which they know to be untrue or should admit to be so since the publication of our book. As far as the Spanish public in particular is concerned, which is at this very moment being told by Guillermo Solana, the director of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, that new gallery space is urgently needed in Malaga and Sant Feliu de Guixols because the Madrid museum is ‘running out of space’, I feel the time has come to tell him that before any more tax funds are poured into Thyssen projects, the Thyssens might be more truthful about their past and that of the collection, while the Spanish government must admit how much they have and are paying the Thyssens for the display and storage of their paintings. |

Celebrating the victory of stud farm Erlenhof's 'Nereide' at the 1936 German Derby. In the centre of the picture are (to the right) the winning horse's owner, Heinrich Thyssen (in grey top hat) and (to the left) his friend and associate Hermann Göring (in white suit) (photo: Tachyphot Berlin, copyright: David R L Litchfield) |

Tags: Anja Seeliger, August Thyssen, Francesca Habsburg, Guillermo Solana, Heinrich Thyssen, Manfred Rasch, Margit Batthyany, Oberbilker Steelworks, Press- and Rolling Works Reisholz, Rechnitz Castle, Rohoncz Collection, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, ThyssenKrupp

June 24th, 2009

| After twenty months of squabbling, discussing, debating and lecturing, many Swiss, German and Austrian academics, film-makers, journalists, politicians, ‘chariticians’ and even a playwright, have still failed to come up with a plausible reason why the people of Rechnitz have allegedly remained so unforthcoming concerning the details of the massacre and burial of two hundred Hungarian Jews in the grounds of Rechnitz Castle in 1945. I never found the people of Rechnitz unforthcoming, but for those who claim they did, I can now reveal the reason for their silence.

Shortly before I issued my statement at the Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre at Vienna University on 5 May 2009, Caroline Schmitz and I met with Professor Pia Janke and her assistant, Christian Schenkermayr, for a drink at Cafe Griensteidl. We were also joined by Teresa Kovacs, a tutor and research associate at the Centre. Most importantly, unlike any of the aforementioned ‘experts’ who claim to have been studying the massacre, Teresa was born and bred in Rechnitz. Her grand-parents worked for Countess Margit Batthyany (nee Thyssen) while her father always spoke openly to her of the tragedy.

Why Teresa chose me as a messenger should have been no more of a puzzle than why Rechnitz originally chose me, via their historian, Professor Josef Hotwagner, to tell their side of the story; or what they were prepared to tell me at the time. Perhaps she also realised that I didn’t and don’t suffer from a conflict of interests. A rare qualification indeed. Particularly in Austria.

But before I decided to publish her statement, I first wanted to see if any of the opinions aired at the Eisenstadt Symposium on 16 October 2008, or the recent series of lectures and discussions at the Jelinek Research Centre would include her explanation. So far, despite the potential immediacy of the internet, nothing has been revealed concerning what was said, apart from an apparent reassurance that reports of the two symposiums would be written, printed, bound and distributed to an undefined readership at some indeterminate time in the future.

When I read a recent article by the Austrian writer Martin Pollack in the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung, once again questioning the motivation of the people of Rechnitz ‘withholding information’, I was somewhat surprised that a man, who had found it so difficult to reveal his own family history, should be asking such a question, rather than supplying the answer. But it also occurred to me that maybe it wasn’t so much the people of the town who were secretive, as the plethora of ‘experts’, who had proved so reluctant to accept the truth.

I believe the reason why Ms Kovacs had decided to tell me what everyone in Rechnitz knows, is because she wants the public to know now. Not in another sixty years’ time.

So this is what she told me that afternoon at Cafe Griensteidl:

‘While Countess Batthyany was in Rechnitz, there was always money around. Her name was never spoken of in connection with the atrocity, only ever in connection with wealth and the beautiful Castle. Basically, the Countess continued to give money and plots of land away to people in Rechnitz right until the 1980s, practically until the day she died’.

It was so wonderfully clear, simple and obvious, it really shouldn’t have come as such a surprise to me. I already knew that Margit’s father, ‘Baron’ Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, had ‘primed the pump’ by bequeathing a plot of land, a specific plot of land, to his Rechnitz forester.

The Castle had always been the very heart and soul of Rechnitz. Without it, the town should have died, but the Castle’s continued existence would have been a memorial to the atrocity. Now, while Margit Thyssen’s money ensured the town’s survival, the ghost of the Castle continues to haunt the town.

As Teresa put it so beautifully: ‘The Castle has gone….but it is still there!’ Elfriede Jelinek could not have put it better. |

Vienna, Burgring, 2009 |

Tags: Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Josef Hotwagner, Margit Batthyany, Margit Thyssen, Martin Pollack, Pia Janke, Rechnitz Castle, Rechnitz Massacre, Teresa Kovacs

June 23rd, 2009

| It is a well-known fact that within the money-obsessed art market, exposing fakes is rarely going to make you friends and certainly little in the way of a profit, which is the main reason why my questioning of many of the paintings in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum has been met with such deafening silence; particularly in Spain.

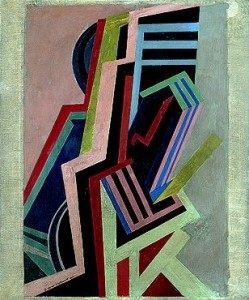

It was thus somewhat reassuring when Brian Sewell, the Evening Standard’s legendary art critic, recently took it upon himself to not only expose a painting from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection claimed to be by Edward Wadsworth as a fake, and question Tate Modern for including it in their ‘Futurism’ exhibition (until 20 September), but also to reveal the reason for such dishonesty.

http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/arts/artexhibition-20656913-details/Futurism/artexhibitionReview.do?reviewId=23709460

Unfortunately, he didn’t question Norman Rosenthal, veteran Exhibitions Secretary at London’s Royal Academy of Arts and now ‘freelance curator to international museums and galleries’, who has been a member of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation in Madrid for some 8 years. How could Rosenthal let ‘Wadsworth’s’ ‘Vorticist Abstraction 1915’ be included in the Tate Modern exhibition? Was it done because its inclusion might ‘give (the painting) respectability’, as Brian Sewell suggests?

It seems clear that Rosenthal is a man who may be sailing dangerously close to acting as both poacher and game-keeper. Indeed, he raised more than a few eyebrows with an article in The Art Newspaper of December 2008, where he advocated the introduction of a statute of limitations on the restitution of Nazi-looted art.

http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/The-time-has-come-for-a-statute-of-limitations/16627

My letter to the editor of The Art Newspaper has remained unpublished; until now:

‘8 December 2008

Dear Sir,

Sir Norman’s article concerning Nazi-looted art in your latest issue is fascinating more for what he doesn’t say than for what he does. Surely, the fact that he is a trustee of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum must present him with a conflict of interest; particularly now that the full extent of the Thyssen-Bornemiszas’ involvement with Göring and the Third Reich has been revealed, and a number of paintings in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection are believed to qualify as Nazi-looted art.

This is a fact that cannot have escaped Norman’s attention, particularly in the case of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum’s Pissarro painting ‘Rue St Honore, Afternoon, Effect of Rain’, which is the subject of a legal action for retrieval by the Cassirer family.

Under the circumstances, Sir Norman’s call for a statute of limitations could unfortunately be seen to be motivated more by his professional interests than his moral judgement’.

http://www.lootedartrecovery.com/looted-art/looted-objects/pending.htm

|

Another Fake Thyssen-Bornemisza (nee Wadsworth) ? |

Tags: Art Restitution, Brian Sewell, Camille Pissarro, Cassirer, Edward Wadsworth, Norman Rosenthal, Tate Modern, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

May 26th, 2009

| The fulfilment of the ambition of Heini Thyssen’s widow, Carmen Cervera, to see her own name in lights on a public museum – rumoured locations for which have so far included Madrid, Seville, Sant Feliu de Guixols and Malaga – continues to hang in the balance, as it has done, now, for some five years.

First political concerns about the plans for a Carmen Thyssen Bornemisza Museum in Malaga were raised in May 2008, when the professor of law at Malaga University and spokesperson for the United Left Party, Pedro Moreno Brenes, urged the local government to stop developing the new museum (for which € 25 million had already been budgeted) until a fully committed contract had been signed.

Then, on 31 March 2009, much was made of Carmen Thyssen and Malaga’s mayor, Francisco de la Torre, signing the papers to set up the foundation which is to manage the museum. Pictures were taken of ‘Tita’ laying the foundation stone.

While de la Torre had apparently been given three catalogues by the ‘Baroness’ from which 200 pictures would be chosen for the museum (on loan for 15 years), and it was claimed they were all “very attractive and interesting”, the opposition has so far failed in their attempts to gain access to an exact and definite list of the proposed works to be exhibited. Names of artists bandied about have included “Zurbaran, Zuloaga and Sorolla”.

On 19 April 2009, Moreno Brenes’s party presented a motion to the town council, critising the “notable legal insecurity” in the ongoing Thyssen negotiations, while adding that the budgeted costs for the Carmen Thyssen Bornemisza Museum of Malaga (to be opened at the end of 2010) had by now increased to € 38 million.

Today comes news that the main opposition party, the PSOE, which forms the national government of Spain, has joined the ranks of the critics of this project. Their spokesperson for the Malaga town government, Rafael Fuentes, has told Europa Press that Mayor de la Torre has “sacrificed the needs of ordinary citizens of Malaga in favour of pet projects of Barons and Earls” and that there is a marked “lack of transparency” in the Thyssen and other projects.

http://www.europapress.es/andalucia/noticia-psoe-critica-pp-ciudad-parada-no-haya-arrimado-hombro-lucha-contra-crisis-20090525152909.html

http://www.europapress.es/autonomias-00175/noticia-iu-insta-pp-conocer-obras-museo-thyssen-garantice-calidad-mismas-20090419112014.html

http://www.laopiniondemalaga.es/secciones/noticia.jsp?pRef=2008052100_2_181054__Malaga-pide-gastar-dinero-Thyssen-hasta-firmar-contrato |

|

Tita Thyssen-Bornemisza cementing her future in Malaga (courtesy of Hola Magazine, 31 March 2009) |

Tags: Carmen Cervera, Carmen Thyssen Bornemisza Museum, Francisco de la Torre, Heini Thyssen, Hola Magazine, Malaga, Pedro Moreno Brenes, Rafael Fuentes, Sant Feliu de Guixols, Tita Thyssen

May 8th, 2009

| During December 2008, I was invited by the Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre at the University of Vienna to take part in a discussion concerning her play ‘Rechnitz (Der Würgeengel)’ to take place in May 2009. Some four weeks prior to the event, I discovered one of the sponsors of the series of lectures and discussions under the title ‘Endless Innocence’ was to be Francesca Habsburg, nee Thyssen, in the form of her art foundation Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (T-B A21). My introductory statement which I gave on the evening of 5 May in Vienna was largely in response to this situation. It read as follows:

‘I would like to say how gratified I am to have played such a major part in persuading Francesca Thyssen to accept, as part of her financial inheritance, some responsibility for her family’s behaviour. I believe this to be manifest in her sponsoring of this event.

However, I would have been even more gratified if she had made an apologetic admission, as opposed to a financial contribution, for being that the Thyssens were sponsors of Rechnitz Castle and the Countess (and I do have documentary evidence of that fact with me tonight), I consider there to be something obscenely ironic about the fact that we are all sitting here, 64 years later, discussing the Rechnitz Massacre, or a play by Elfriede Jelinek, which includes the massacre, while yet again being sponsored by The Thyssens in the form of Francesca’s art foundation.

I am also forced to question how, as long as any doubt remains concerning the extent of the Thyssens’ involvement in the Rechnitz Massacre, Vienna University can accept her money while claiming impartiality.

Unfortunately, this conflict of interest is not a unique situation in the academic world, particularly in the case of Wolfgang Benz, head of Anti-Semitism Research at the Technical University of Berlin, and Richard Evans, Chairman of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University, who have both attempted to discredit my writing in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and my book, ‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, published in Germany under the title ‘Die Thyssen-Dynastie’, while accepting funding from the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung.

I am sad to say that I consider this type of arrangement brings into question the credibility of academic historians.

I now have another question. If Countess Margit Batthyany, nee Thyssen, sponsored the murder of 200 Hungarian Jews as after-dinner entertainment and possibly even played an active role in their murder, and then Elfriede Jelinek writes a play involving the atrocity, which can also be characterised as entertainment, albeit intellectual entertainment, but which I’m sure everyone here considers a work of art, where does that leave the killing of the Jews?

As I hope and believe is obvious from my article in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and my book ‘Die Thyssen-Dynastie’, I consider it a crime against humanity. And no amount of art sponsorship, intellectual smoke screens or academic denial is ever going to alter that.’

I was subsequently informed that Francesca had promised the university to make a public statement, but had failed to do so, despite numerous reminders, prior to her departure to her house in Jamaica.

http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20090515/social/social3.html

(For the German version of my statement, please go to ‘Events’). |

Vienna University, Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre  The Reich and the Habsburgs working together in public & private partnership  Professor Janke of the Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre still experiencing difficulties appreciating what constitutes freedom of speech |

Tags: Elfriede Jelinek, Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre, Francesca Habsburg, Francesca Thyssen, Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, Margit Batthyany, Rechnitz Castle, Rechnitz Massacre, Richard Evans, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Wolfgang Benz

April 22nd, 2009

Fellini once said:

“The pearl is an oyster’s autobiography”.

This is my grain of sand.

|

|

|