Posts Tagged ‘Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza’

Monday, May 3rd, 2010

| Quite why ThyssenKrupp have waited so long to authorise their archivist and historian, Manfred Rasch, to bring out a book of letters between August Thyssen and his son Heinrich, seems somewhat of a mystery. The two men have, after all, been dead for 84 and 63 years respectively. But the professor appears to confirm my belief that this is part of the corporate and family response to my book, by including a rather bizarre statement amongst the credits, which runs thus (page 10):

‘People who are less interested in historically substantiated studies with traceable references and who would rather form their opinions based on sex-and-crime journalism might be entertained by Litchfield, David: The Thyssen Art Macabre, London 2006 (German edition: Die Thyssen-Dynastie, Die Wahrheit hinter dem Mythos, Oberhausen 2008).’

I feel such a statement says more about Rasch than it does about me, and I appreciate the publicity it has afforded my book, including the increase in visits to this website, particularly from the Ruhr district. However, a recent critical review awarded Rasch’s book on Amazon by a reader in Munich might have been unlikely to have imbued him with a similar spirit of generosity:

‘Unfortunately, the title of this book is somewhat misleading, as of the 214 letters only 4 are by Heinrich Thyssen’s hand. It also does not limit the scope of its contents to the years 1919-1926 but includes furthermore a considerable amount of historical material on the history of the Thyssen family and its industries which has been written by Professor Manfred Rasch who is listed as editor of the book. As Professor Rasch is also the head of the archives at ThyssenKrupp, it makes it difficult to accept the impartiality of his views. The style of the book is academic and thus requires an overwhelming interest in the subject matter, as much is being taken up with supportive material in the form of bibliography, sources, commentaries etc.

One also gets the impression that this book, despite its size and the obvious complexity of the research, was in fact created in some haste, as on far too many occasions it sidesteps various historical issues by announcing that scientific research is still ongoing. But what I find even more surprising is the way Prof. Rasch deals with other authors, some of whom have published considerable research about the subject, for instance the Briton David R L Litchfield (‘The Thyssen Art Macabre’, in German: ‘Die Thyssen-Dynastie’), whose description of the murder of 180 Hungarian slave labourers during a party organised at Rechnitz Castle by Margit Thyssen-Bornemisza caused a big stir a few years ago. Prof. Rasch suggests that his readers should view Litchfield’s book as mere entertainment: just an alarming error of judgement or a worrying example of professional jealousy?

This is particularly disturbing in the light of the anti-Semitism in the Thyssen family (see letters dated 9.9.1919, 21.7.1923 and 30.7.1923) which the book presents to the interested public. All in all, however, this is a fascinating read which contains much material of interest to both amateur and professional historians’.

One certainly gets the impression that the corporation may now be trying somewhat too hard to paper over the cracks in their historiography. You may no longer be able to see the cracks but you can certainly see where they have been, which only serves to draw attention to the papering.

I was also particularly interested in the impression that ThyssenKrupp is now giving of having archives that are open to the public. This was certainly not the case when we were researching our book. In fact quite the opposite. However, Rasch still seems determined to believe that, having been denied access to his archives, we chose to create our book without documentary evidence. This is of course totally and completely inaccurate and an opinion that appears to have been based on his wishful thinking.

Apart from the fact that our book is most certainly based on fully documented evidence, Rasch, who is obviously holding me responsible for the cracks in his professional credibility, would perhaps have been better advised not to talk of ‘entertainment’ in connection with a family that was responsible for the financing and use of slave labour, in particular (but not exclusively) in the context of the Rechnitz massacre (which Rasch chooses to ignore, apart from providing a link to an Austrian website).

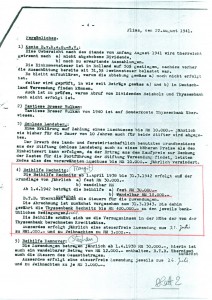

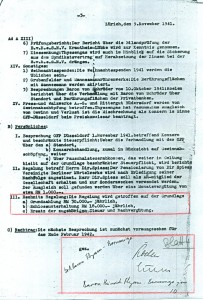

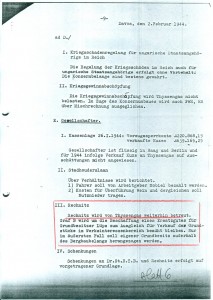

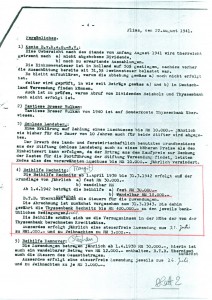

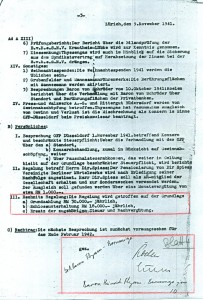

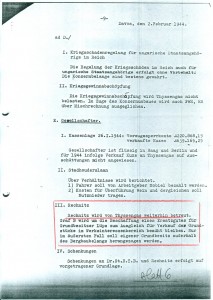

To assist Manfred Rasch with future editions of his book, I include in this post excerpts of documents confirming the Thyssens’ war-time financing of their SS-occupied castle in Rechnitz, documents which I can only assume he overlooked in his haste to publish his book. They concern meetings of Heinrich and his son Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza (‘Heini’) with their managers Heinrich Lübke and Wilhelm Roelen on 22 August 1941 in Flims, on 9 November 1941 in Zurich and on 2 February 1944 in Davos and include details of the RM 400,000 loan from August Thyssen Bank Berlin to Rechnitz, yearly contributions of RM 30,000 for Margit Batthyany and RM 18,000 for the upkeep of the castle, as well as a notification that Thyssengas (then Thyssensche Gas- und Wasserwerke) was generally ‘looking after’ Rechnitz.

Scanned Document

Scanned Document-1

Scanned Document-2

(all excerpts of documents in this post are from the archives of David R L Litchfield and are to be reproduced with his permission only). |

ThyssenKrupp's historian and archivist Prof. Manfred Rasch  Documents substantiating Thyssen funding of Rechnitz castle during the second World War (Archives of David R L Litchfield, not to be reproduced without permission)  Documents substantiating Thyssen funding of Rechnitz castle during the second World War (Archives of David R L Litchfield, not to be reproduced without permission)  Documents substantiating Thyssen funding of Rechnitz castle during the second World War (Archives of David R L Litchfield, not to be reproduced without permission) |

|

Tags: Amazon, anti-Semitism, archives, August Thyssen, August Thyssen Bank, Berlin, bibliography, Davos, Flims, Heinrich Lübke, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, historiography, Manfred Rasch, Margit Batthyany, Rechnitz, Ruhr, slave labour, sources, Thyssengas, ThyssenKrupp, Thyssensche Gas- und Wasserwerke, Wilhelm Roelen, Zurich

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Corporate, Thyssen Family Comments Off on What have ThyssenKrupp’s historians been doing all this time?

Tuesday, April 27th, 2010

| Aus dem DIG Magazin (1/2010), Seite 29:

‘Adel verpflichtet. So sagt das Sprichwort. Aber wozu verpflichtet Adel?

Der Brite David Litchfield bekam durch seine Bekanntschaft zu ‘Heini’ Thyssen Einblicke in die Unterlagen der Familie Thyssen.

Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza wurde 1921 als Sohn des gleichnamigen Vaters geboren. Sein Onkel Fritz hatte Anfang der dreissiger Jahre eine unrühmliche Rolle bei der Machtergreifung Hitlers gespielt und die Gunst der Stunde genutzt, um sich und seine Familie kräftig zu bereichern. Der “Führer” belohnte den Grossindustriellen mit einem Sitz im Reichstag. Schon 1934 kam es zu Spannungen zwischen Thyssen und Hitler, 1939 gar zum Bruch. Trotz seiner Flucht wurden die Nazis seiner habhaft und verschleppten ihn ins KZ. Hermann Göring hielt indes seine schützende Hand über Fritz Thyssen.

Gleichwohl machte die Familie Thyssen glänzende Geschäfte im Krieg. ‘Heini’ Thyssen, ein gut aussehender Jüngling, erlebte erste Liebschaften und rettete sich in die Schweiz. In den Alpen verlebte er den Krieg.

Untrennbar mit dem Namen Thyssen verbunden ist ein Massaker in Rechnitz. Kurz vor dem Einmarsch der Roten Armee veranstaltete Gräfin Batthyany, eine geborene Thyssen, eine Sause auf ihrem Schloss mit hochrangigen Nazis und SS-Offizieren. Die betrunkenen Anwesenden machten sich einen Spass daraus, etwa 200 Juden abzuschlachten. Muss erwähnt werden, dass die adeligen Gastgeber für dieses Verbrechen nie juristisch belangt wurden?

‘Heini’ Thyssen folgte seinem Vater als Chef des Hauses. Mit seinen Geschwistern lieferte er sich einen heftigen Erbstreit um die Macht. Es folgten Jahre als Playboy: Geld, Macht, Liebe.

Das Buch ist gut geschrieben. Dort, wo Aussagen der Familienmitglieder nicht durch Quellen belegt sind, hinterfragt Litchfield diese Aussagen. Er beleuchtet das Treiben einer Familie, in der Geld alles ist.

Wozu Adel verpflichtet, weiss ich nach der Lektüre des Buches immer noch nicht, aber das Treiben der Familie Thyssen erinnert an etwas anderes: Geschichte verpflichtet. Nämlich zur Verantwortung.’

(Deutsch-Israelische Gesellschaft, Magazin 1/2010, Rezensionen, s. 29/30, Dr Norbert Korfmacher, ‘Eine Unternehmensgeschichte: Die Thyssen-Dynastie’).

http://www.deutsch-israelische-gesellschaft.de/

http://www.bamby.de/mylife.htm |

|

Tags: Adel verpflichtet, David Litchfield, Deutsch-Israelische Gesellschaft, Die Thyssen-Dynastie, Dr Norbert Korfmacher, Fritz Thyssen, Geschichte, Gräfin Batthyany, Heini Thyssen, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Hermann Göring, Rechnitz, Reichstag, Schweiz, Unternehmensgeschichte, Verantwortung

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Family Comments Off on Dr Norbert Korfmacher Rezensiert ‘Die Thyssen-Dynastie’ (assoVerlag, Oberhausen/Ruhr) für die Deutsch-Israelische Gesellschaft

Thursday, March 4th, 2010

| Dear Manfred Rasch (‘Ueberspieler’, ThyssenKrupp Smoke and Mirrors Department),

Congratulations on your latest literary output, but I am confused. When we came to see you in November 1998, you told me that the letters between August Thyssen and his son Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza were Baron Heini Thyssen’s private property.

You also told us: ‘We are not a service organisation for the Thyssen family. We are the archive of a company or companies, and have nothing to do with the Thyssen-Bornemisza family.’ Were you lying or has something changed? So: Who owns the copyright to your book and/or to the letters? All very mysterious!

I am certainly looking forward to receiving a copy of the book, not so much because of what it will contain, but what it doesn’t. Fortunately, as we also have copies of all the letters, which were given to us by Heini Thyssen, we can fill in any gaps you might inadvertently have left. We hope nobody has been tempted to forge any additions, as you once accused us of doing.

I have to say that I find the fact that you, and presumably ‘the organisation’, are choosing to do such a book, while ThyssenKrupp is the subject of ‘independent’ academic research, deeply suspicious. Why do I get the feeling that it is all part of the re-writing of corporate and family history in response to the publication of our book ‘Die Thyssen-Dynastie. Die Wahrheit hinter dem Mythos’ (assoVerlag Oberhausen, 2008)? |

|

Tags: assoVerlag, August Thyssen, Heini Thyssen, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Manfred Rasch, Oberhausen, ThyssenKrupp

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Corporate, Thyssen Family Comments Off on Private Enterprise?

Wednesday, October 28th, 2009

| Dear Author of Tavarua – The Traveler Blogspot,

I feel compelled to comment on your post dated 21 October entitled ‘A Legendary Art Collector’, where you repeat several of the Thyssen mantras, including that the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection was once housed at the family castle in Hungary. How far away from the truth you are can be seen from the evidence as described in our book. For instance, the foreword to the first exhibition of this collection, which took place in Munich in 1930, is extremely explicit and I will quote the most relevant passages from it to illustrate my comment to you:

‘…It was known to the inner circle of experts that during the last few years, shielded from the public, the basis for a new collection was created in Germany…..Even the owner and creator of the collection so far renounced the pleasure of seeing all of his treasures assembled in one place. Rather, he left them first of all under the seal of confidentiality in all those various locations where they had been acquired. This is why the Directorate of the Bavarian State Art Collections were so grateful and excited when, upon their suggestion, the collector Dr Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza decided to assemble the works, dispersed in Paris, The Hague, London, Berlin and other cities, temporarily in Munich and to entrust them to the ‘Neue Pinakothek’ for an exhibition…

…Here they are gathered for the first time to be appreciated by the public. One will note with amazement what has been possible in a surprisingly short period of time…I only wish to point out that it was possible to use the big movements on the art market, which the recent turmoils have brought with them, with circumspection and energy……

…Here they are: an exquisite male portrait by Michael Pacher and a female portrait by Albrecht Altdorfer, which we wholeheartedly commend as one of the high points of German art, as the perfect representation of German womanhood of that time in insurpassable truth and freedom…

…This new creation stands entirely alone in our German present……We believe that the national treasure can experience no greater enhancement and grounding than through the acquisition of great, noble works of art…

…The increasing impoverishment of our ‘Volk’ [the German people] and the financial crisis of our stately powers, which are becoming more dangerous every day, make us fear that the maintenance of cultural institutions will fall behind more and more…

…Dr Rudolf Heinemann-Fleischmann also carried out the laborious task of gathering all the works to be exhibited from their various locations….’ (Dr Fr Dörnhöffer, Munich, June 1930).

The sad truth about the Thyssen connection with Rechnitz (which has been Austrian, rather than Hungarian since 1921, before which it was known as Rohoncz) is that to this day the Thyssen family uses the name of the place to hide both the real provenance of their paintings and their own national provenance, which was firmly German, not Hungarian, Swiss, or anything else. This would not be quite as bad if, in March 1945, an appalling crime had not taken place in Rechnitz, which has tarnished the town’s image for ever.

The fact that, to this day, the Thyssens refuse to own up to their involvement in the Rechnitz Massacre of over 180 Jewish slave labourers to my mind makes their continued use of the town’s good name as a cloak for the early years of their collection especially distasteful. |

Jan Lievens, 'Rest on the Flight into Egypt' (ca. 1635): The first painting purchased for the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection (Rohoncz Collection), in the year 1928. It never went anywhere near Rohoncz (Rechnitz) Castle and neither did any of the other 542 of Heinrich Thyssen's paintings. |

Tags: Albrecht Altdorfer, Dr Rudolf Heinemann-Fleischmann, Germany, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Hungary, Jan Lievens, Michael Pacher, Neue Pinakothek, Rechnitz Castle, Rechnitz Massacre, Rest On The Flight To Egypt, Rohoncz Collection, Tavarua Blogspot, The ThyssenArt Beast, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Art Comments Off on The ThyssenArt Beast (1928-2009): A Letter To Tavarua Blogspot (by Caroline Schmitz)

Sunday, October 25th, 2009

Book Review by Dr Erika Abcynski, Dormagen, Germany (translated by Caroline Schmitz):

‘David R L Litchfield has written a book about the Thyssen family from the founding of the Thyssen Concern to its collapse. Litchfield has assembled much interesting information about the Thyssens and thus about German capitalism per se.

As early as the founding of the first Thyssen works in 1870 August Thyssen combined greed, cleverness and sharp practice against his first business partner and brother-in-law as well as the elimination of competitors and the procurement of capital through marriage. Indeed, he concealed from his brother-in-law that he wanted to found his own rolling work in direct competition to him. The company Bechem & Keetman in Duisburg had to produce machinery exclusively for him. In the area surrounding Duisburg nobody but August Thyssen was able to buy machinery for a rolling work.

For the workers of the Thyssen works there was the rule of carrot and stick. “August’s expectations of his workers were very simple and straightforward. He expected them to abide by the ‘Reglement’, work very hard with the minimum of waste in time or materials, and produce as much as their engineer managers could get out of them…..The Meisters were expected to act as sub-contracting entrepreneurs rather than production or workshop supervisors of their respective departments”.

“The workers… remained entrapped by the Thyssens’ policy of supplying, and owning, all the worker’s needs ‘on-site’. The story, baths, canteens and lodging houses were all a man had time to need.” (quoted from David Litchfield, ‘Die Thyssen-Dynastie’). People were fired for minute transgressions. In 1928 the Thyssen-brothers Fritz and Heinrich locked out 225,000 workers for one month. Through the ownership of 67,000 workers’ lodgings, pressure could be exerted on the workforce and the government could be blackmailed through the threat of mass redundancies.

The Thyssen balance sheet for 1912 claimed the value of the Concern to be 562,153,182 Reichsmark. Before and during the First World War, there was strong collaboration between Thyssen and the Imperial government. One of August Thyssen’s friends was Hjalmar Schacht, later Hitler’s Economics Minister. Thyssens armaments production for German increased. By 1918, practically the whole enterprise produced for the war. The founding of firms in The Netherlands safeguarded Thyssen assets in case the war would be lost. Furthermore, tricks were used through the Thyssen-owned Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart NV and assets safeguarded. Using the Hungarian citizenship of the Thyssen-son Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, topped by a residency in the Netherlands, the Thyssen fortune was protected from allied confiscation, also after 1945. Heinrich Thyssen had married the daughter of the Hungarian Baron Bornemisza and had had himself adopted by his father-in-law in order to gain the title of Baron.

In 1923 there were the first contacts to Hitler. Fritz Thyssen knew about the plans for the putsch. He donated 100,000 Goldmarks for the National Socialist Party. He liked the fact that Hitler wanted to sort out the workers’ movement once and for all. At the beginning of the 1940s, Fritz Thyssen conceded that he had donated 62 million Reichsmark to the Nazi party over a 12 year period. Göring was one of his friends. In 1933 Fritz Thyssen joined the Nazi party, his wife had done so even earlier.

Tax evasion was an important business tool for the Thyssens. From 1919 to 1939 there were constant investigations by the financial authorities. In 1939 the Tax Directorate in Düsseldorf was able to prove that Fritz Thyssen had committed tax evasion and illegal foreign currency transactions, which Hitler had declared to be a capital offense. A fearful Fritz left for Switzerland on 1. September 1939, then moved to France. All his assets were placed by Göring under the trusteeship of Prussia and managed by joint friends and business partners of the two men. In other words, it was not his enmity against Hitler or any concerns about the mistreatment of Jews that led to Fritz Thyssen’s persecution, but the fact he was lining his own pockets. From the 1930s the Thyssens once again made money from armaments production, but also began simultaneously, just like August Thyssen during WWI, to safeguard their fortune, for instance in the USA and in South America. August Thyssen Hütte had nine POW-camps and seventeen camps for forced labourers. Heinrich Thyssen lived in Switzerland, led the affairs of his firms from there and continued to do business with the Nazis, but not publicly. From 1941 onwards he made his son Heini attend the meetings in Switzerland with the managers of his enterprises, which were also sometimes attended by Baron von Schröder of the Nazi bank Stein in Cologne, who was the trustee for Fritz’s confiscated industrial shares.

The most disgraceful story which members of the Thyssen family were involved in, is the murder of 200 Jews at Rechnitz Castle, where the eldest daughter of Heinrich Thyssen, Margit Batthyany, nee Thyssen-Bornemisza, lived with her husband, Count Batthyany, and high-ranking Nazis and SS-officers. During the night of 24 March 1945 the Ortsgruppen-leader Podezin, a Gestapo-official, left a party hosted by Count and Countess Batthyany with guests to shoot the Jews. The victims were 200 half-starved Jews who had been declared unfit for work. Local people said that Podezin had been in the habit of shooting Jews who were locked up in the castle cellars and that the Countess had enjoyed watching these events. After the war neither Margit nor other members of the Thyssen family wanted to know anything about this massacre and they were never prosecuted for it.

Litchfield has also assembled much information about the behaviour of the Americans and the British towards the Thyssens. For fear of the communists the Thyssens were handed back all of their fortune, works, shares and gold, despite their role in the Third Reich.

After 1945, Heinrich Thyssen transferred his role within the Thyssen Bornemisza Group to his son Heini Thyssen. But he did not much care for the Concern. Rather, he spent most of his time with sharing out his fortune. Other than that he had many relationships with glamorous, high society women and with the excesses of alcoholism. As a form of investment he bought many hundreds of paintings which were first exhibited and stored at his father’s villa in Switzerland. August Thyssen had started the art collection by buying works of Rodin, also as an investment. When Heini realised, that the maintenance of his collection was expensive, he searched for another way of handling it. Here he used all of his business acumen and various goods contacts, thus managing to sell about half of his art works to the Spanish state for 350 million dollars, payable free of tax, outside Spain, having first loaned the collection to the Spanish for 5 million dollars a year. The Spanish state met all costs for the use of the Thyssen pictures as a permanent public display.

The facts assembled in this review represent only a tiny fraction of the innumerable data painstakingly collected by Litchfield, which illustrate the greed and corruption of the Thyssens. The book is over 500 pages long and a thrilling read, the part about Heini Thyssen is somewhat too extensive.’

http://www.secarts.org/journal/index.php?show=article&id=948&PHPSESSID=ec1b0e599e946f1f299627d9346a7f4a

Tags: Adolf Hitler, Alcoholism, Armaments Production, August Thyssen, Auguste Rodin, Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart, Bankhaus J. H. Stein, Duisburg, First World War, Forced Labour, Fritz Thyssen, Heini Thyssen, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Hermann Göring, Kurt von Schröder, Margit Batthyany, National Socialist Party, Rechnitz Castle, Second World War, Thyssen Dynasty, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Art, Thyssen Corporate, Thyssen Family Comments Off on ‘The Thyssen Dynasty – A Masterclass In The Unacceptable Face Of Capitalism’

Wednesday, June 24th, 2009

| After twenty months of squabbling, discussing, debating and lecturing, many Swiss, German and Austrian academics, film-makers, journalists, politicians, ‘chariticians’ and even a playwright, have still failed to come up with a plausible reason why the people of Rechnitz have allegedly remained so unforthcoming concerning the details of the massacre and burial of two hundred Hungarian Jews in the grounds of Rechnitz Castle in 1945. I never found the people of Rechnitz unforthcoming, but for those who claim they did, I can now reveal the reason for their silence.

Shortly before I issued my statement at the Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre at Vienna University on 5 May 2009, Caroline Schmitz and I met with Professor Pia Janke and her assistant, Christian Schenkermayr, for a drink at Cafe Griensteidl. We were also joined by Teresa Kovacs, a tutor and research associate at the Centre. Most importantly, unlike any of the aforementioned ‘experts’ who claim to have been studying the massacre, Teresa was born and bred in Rechnitz. Her grand-parents worked for Countess Margit Batthyany (nee Thyssen) while her father always spoke openly to her of the tragedy.

Why Teresa chose me as a messenger should have been no more of a puzzle than why Rechnitz originally chose me, via their historian, Professor Josef Hotwagner, to tell their side of the story; or what they were prepared to tell me at the time. Perhaps she also realised that I didn’t and don’t suffer from a conflict of interests. A rare qualification indeed. Particularly in Austria.

But before I decided to publish her statement, I first wanted to see if any of the opinions aired at the Eisenstadt Symposium on 16 October 2008, or the recent series of lectures and discussions at the Jelinek Research Centre would include her explanation. So far, despite the potential immediacy of the internet, nothing has been revealed concerning what was said, apart from an apparent reassurance that reports of the two symposiums would be written, printed, bound and distributed to an undefined readership at some indeterminate time in the future.

When I read a recent article by the Austrian writer Martin Pollack in the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung, once again questioning the motivation of the people of Rechnitz ‘withholding information’, I was somewhat surprised that a man, who had found it so difficult to reveal his own family history, should be asking such a question, rather than supplying the answer. But it also occurred to me that maybe it wasn’t so much the people of the town who were secretive, as the plethora of ‘experts’, who had proved so reluctant to accept the truth.

I believe the reason why Ms Kovacs had decided to tell me what everyone in Rechnitz knows, is because she wants the public to know now. Not in another sixty years’ time.

So this is what she told me that afternoon at Cafe Griensteidl:

‘While Countess Batthyany was in Rechnitz, there was always money around. Her name was never spoken of in connection with the atrocity, only ever in connection with wealth and the beautiful Castle. Basically, the Countess continued to give money and plots of land away to people in Rechnitz right until the 1980s, practically until the day she died’.

It was so wonderfully clear, simple and obvious, it really shouldn’t have come as such a surprise to me. I already knew that Margit’s father, ‘Baron’ Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, had ‘primed the pump’ by bequeathing a plot of land, a specific plot of land, to his Rechnitz forester.

The Castle had always been the very heart and soul of Rechnitz. Without it, the town should have died, but the Castle’s continued existence would have been a memorial to the atrocity. Now, while Margit Thyssen’s money ensured the town’s survival, the ghost of the Castle continues to haunt the town.

As Teresa put it so beautifully: ‘The Castle has gone….but it is still there!’ Elfriede Jelinek could not have put it better. |

Vienna, Burgring, 2009 |

Tags: Elfriede Jelinek Research Centre, Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Josef Hotwagner, Margit Batthyany, Margit Thyssen, Martin Pollack, Pia Janke, Rechnitz Castle, Rechnitz Massacre, Teresa Kovacs

Posted in The Thyssen Art Macabre, Thyssen Family Comments Off on Reason For Rechnitz Silence Revealed

|